Jafar Panahi | 1hr 42min

Stray dogs roam the margins of Iranian life in It Was Just an Accident, chasing cars down rural backroads and aimlessly wandering Tehran’s city streets. No one pays them much attention – they are simply part of the dusty backdrop, their distant barks filling the air when all else is quiet.

The moment that Rashid hits and kills one while driving his family though, we begin to recognise these animals as more than just background noise. In the single, unbroken take of this opening scene, he pulls over, steps outside, and drags the dog off the road, washed in the vehicle’s red brake lights. As if to block out the dead creature, Jafar Panahi’s camera does not widen to any more than a mid-shot, and when it returns to the front-on angle through the windscreen, Rashid is now thoroughly isolated in the frame. “You killed it,” his daughter murmurs. “It was just an accident,” his wife insists, though such attempts at downplaying his accountability are unconvincing. A disturbed expression settles across Rashid’s face, and we begin to sense a guilt that festers beneath the surface.

As a former assistant to director Abbas Kiarostami, Panahi has long blurred the lines between documentary and fiction, yet the complex moral dilemma which arises in It Was Just an Accident often seems far more evocative of his contemporary, Asghar Farhadi. Using dogs as the film’s central motif of society’s downtrodden, Panahi frames his narrative within the larger context of Iran’s oppressive regime and the enduring trauma borne by its political prisoners – a trauma that Panahi himself knows intimately. Due to his vocal criticism of its Islamic government, he has been imprisoned multiple times for his dissent, and was forced to direct It Was Just an Accident in secrecy due to his filmmaking ban. Drawing from his own lived experience, Panahi thus channels his fury and grief into the character Vahid, whose run-in with Rashid leads him to believe that this is the man who once brutally tortured him in captivity.

Like his fellow prisoners, Vahid was blindfolded during his time in detention. As a result, it isn’t Rashid’s face that Vahid recognises when the man drops by his mechanic shop to repair his car, but rather the faint, rhythmic squeak of an artificial leg. Though many knew him as Peg Leg or the Gimp, Eqbal is the name that few have managed to shake from their nightmares, so doubt naturally settles in when inconsistencies between his and Rashid’s identity begin to surface. Having kidnapped his target, driven him into the desert, and dug him a grave, Vahid is on the verge of killing his supposed tormentor once and for all – yet wouldn’t the act of killing a potentially innocent man only perpetuate the cycles of violence once inflicted on him?

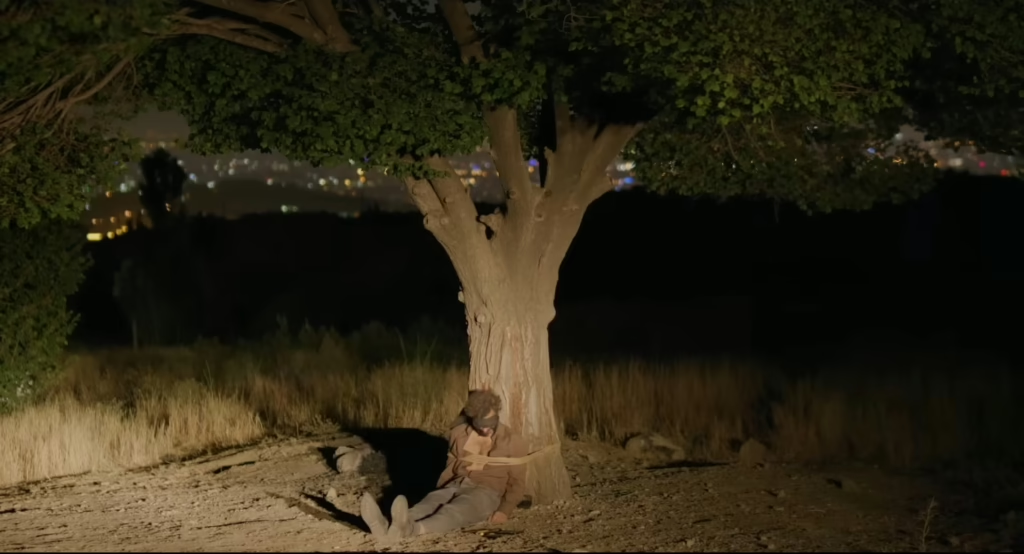

By employing continuous shots and resisting mid-scene cuts, Panahi cultivates a subdued, stripped-back realism in It Was Just an Accident, organically revealing the discomfort of each ethical debate and painful indecision. He is not a particularly aesthetic filmmaker, yet the wide shot of Vahid’s white van, Rashid’s grave, and a withered black tree evenly spaced across the desert landscape offers a stark, visual poetry that punctuates his otherwise restrained style. Rising up in the background too, a barren mountain range frames the composition with stark grandeur, and the sheer duration spent dwelling on this shot deepens the tension of Vahid’s moral compromise. Suddenly plagued with uncertainty, he thus sets off on a quest to validate his suspicion, calling upon the aid of friends and strangers whose recollections may hopefully shed some light on the truth.

Panahi’s visual storytelling excels in these early scenes where Vahid operates alone, withholding exposition that might clue us into his motives, and lingering on his visible, seething hatred. Instead, we are only drip-fed details as more accomplices join his mission, gradually mounting a case for their shared pursuit of justice. As such, Panahi allows us to feel the weight of Vahid’s resentment before we fully understand it, patiently earning our emotional investment in his retribution.

Through the diversity of Vahid’s growing entourage as well, Panahi effectively draws out their ideological tensions, mapping a spectrum that extends from compassionate forgiveness through to unrelenting vengeance. Any man guilty enough to be executed has already dug his own grave, bookseller Salar sombrely insists, hoping to move forward with his life – though he is at least willing to share the phone number of an old friend who might be more willing to identify the captive. Wedding photographer Shiva quickly overcomes her stubborn resistance to Vahid’s appeal when he reveals an incapacitated Rashid in his van, while the subject of her shoot, Goli, shifts from innocent bride to unforgiving vigilante upon realising the supposed presence of her former torturer. With her reluctant fiancé Ali joining the party too, they set out to secure the help of another survivor, Hamid – and in him, we find the most violent, vindictive soul of them all.

Panahi’s characterisations are strong across this entire ensemble, giving each an opportunity to challenge the others with their convictions and emotional baggage. Should they kill Rashid and he is truly innocent, then he will be guaranteed a spot in heaven anyway, Hamid maliciously reasons, while Vahid asserts that no action will be taken until the suspect confesses. If there is a unifying factor among them, then it is the common recognition of Peg Leg’s grotesque, sadistic brutality, though even this certainty is complicated by the lingering question of whether he was merely a submissive agent in a dehumanising system. Panahi weaves touches of light humour throughout this mission, particularly contrasting the image of Goli in her bridal gown against otherwise grim circumstances, though none of this undermines the personal stakes at play. Instead, the fleeting comedy emphasises the extreme lengths to which these survivors will go for the sake of catharsis, even compromising the sanctity of one’s own wedding.

When Rashid’s family are inevitably drawn into this entanglement as well, Panahi deepens his narrative focus, confronting the fundamentally human paradox between the impulse for vengeance and the capacity for compassion. Burdened by rage and a profound sense of ethical obligation, Vahid finds a new responsibility unexpectedly thrust upon him, ironically protecting the lives of innocents tied to his tormentor. Even if Rashid is guilty, what justice is truly served when retribution is inflicted on those who played no part in the crime? Even if he is deserving of condemnation, isn’t there something to be said for the humanity that persists beneath acts of cruelty, shading righteous judgement with uncomfortable ambiguity?

It is not necessarily truth which Panahi seeks in It Was Just an Accident, but rather emotional resolution, growing ever more elusive. The ten-minute shot which punctuates the film’s climax reiterates the red lighting from the opening scene, landing us in hell with Vahid, Shiva, and Rashid as they agonisingly reopen old wounds, yet still denying themselves the catharsis they seek in a world torn apart by political violence and collective trauma. Eqbal may have considered his victims little more than stray dogs, yet to Vahid, these survivors are the “living dead” – condemned to relive their pain in the hope of healing it. Nevertheless, neither mercy nor retaliation seems to ease the suffering inflicted on the people of Iran.

Indeed, the final shot of It Was Just an Accident may be the most haunting of all, uneasily lingering on the back of Vahid’s head as he is gripped by a creeping paranoia. Even when the overt terror of Eqbal fades with the rhythmic squeak of his artificial leg, still its memory hangs in the air like a ghost, casting an even darker shadow over Vahid’s life than before. No civilian is ever truly safe under this repressive regime, and beneath the illusion of closure, Panahi chillingly distils the gnawing, unrelenting anxiety of tortured survival.

It Was Just an Accident is coming to Australian cinemas on 29 January, 2026.