Yasujirō Ozu | 1hr 59min

When Yasujirō Ozu directed A Story of Floating Weeds back in 1934, the trajectory of his entire career changed. It is in that early triumph where his pillow shots, meticulous compositions, and meditative rhythms began to take cinematic form, carefully tracing the tensions that arise when an actors troupe arrives in town, and solidifying a visual language that went on to shape his aesthetic philosophy.

At first glance, it would seem redundant for a director known for his stylistic consistency to remake an early success, yet Floating Weeds stands as a powerful testament to Ozu’s artistic evolution over the decades. His gradual shift away from melodrama and towards subdued introspection is made fully apparent by the comparison, offering greater empathy to the troupe leader than before, and lightening the stigma once attached to his profession. In this era of rapid modernisation, it is rather the erosion of old traditions that becomes the film’s melancholic core, as Komajuro’s fading relevance parallels his strained bonds with family, friends, and colleagues.

Formally as well, the time was ripe in 1959 to reinvigorate this silent, black-and-white film with Technicolor vibrance, revelling in the decorative details that bring life to this modest coastal village. Crimson flowers and drapes burst against the cooler tones of Ozu’s mise-en-scene, while stained glass windows colourfully arrange a grid-like pattern in the local sake bar. At the town’s outmost peninsula too, a white lighthouse becomes the focal point of many minimalist compositions, vertically mirroring foregrounded bottles or fishermen, and rising into a pale sky – “blue as a tragedy,” as one character puts it. For the residents, this building is just another unremarkable piece of infrastructure, yet to Ozu it is a beacon that recurringly anchors us within the landscape of daily life.

Unlike its 1930s predecessor, the seaside community of Floating Weeds is not caught in the bleak grip of the Great Depression, but rather striving towards a radiant future its elders have no part in. Even the score carries a Felliniesque, whimsical edge, as if woven from the animated gossip that drifts through town. Judging by the Greek chorus of troupe actors who intermittently comment on the offstage drama, it’s clear that the real spectacle lies more in everyday theatre than Komajuro’s show, which barely inspires any excitement at all. His performance is a bit hammy, his illegitimate son Kiyoshi informs him, and even he admits that it isn’t terribly sophisticated. Audiences these days simply don’t care for quality plays like they used to, the humbled troupe leader reasons, so there’s no point playing to that market.

Besides, what could possibly be more tantalising than the scandal which entangles this father and son in a web of secrets? Not even Kiyoshi is aware of his true parentage, and that is the way troupe leader prefers it, hoping his offspring might pursue a more successful life without being tied to his lowly heritage. When Komajuro’s current girlfriend Sumiko uncovers the truth though, contempt coils into anger, staging these lovers on either side of a rainy alleyway as they hurl vitriol at each other. He should be thankful for the trouble she has gotten him out of, Sumiko bitterly snaps, though he equally throws back that he lifted her out of a life as a common bathhouse whore.

“My son’s different from your type. He belongs to a higher race!”

Drawn to a stalemate, Sumiko thus seeks even greater vengeance – to corrupt Kiyoshi through romantic association with someone of her “type.” Young actress Otaka is the perfect honeypot, and all it takes is a little encouragement to nudge her towards Kiyoshi, who immediately falls for her wiles. By the time Komajuro has caught on to the ploy as well, it is far too late. Not only is Kiyoshi deeply in love with Otaka, but she admits too that her malicious intentions have fallen away to genuine affection.

“It doesn’t matter how it began,” Kiyoshi assures her, sealing their relationship with a kiss between down by the harbour. There, a pair of dry-docked ships impose a formidable architectural presence upon their tiny figures, yet it is precisely within this overwhelming scale that their love feels most hopeful – not that Komajuro sees it this way. Driven to resolve the situation, he indefinitely draws out the troupe’s stay in town, and Ozu slows down the narrative through pillow shots that dwell on rocky shorelines and litter rustling in the warm summer breeze.

Much like Komajuro’s actors, we can see the end of the troupe coming from a distance. As work grinds to a halt, the time comes for them all to split up, beginning with supporting player Kichi who runs off with his fellow performers’ money and belongings. Gathering in the dim, green interior of the local theatre, it becomes woefully apparent that everyone has already made plans to find employment elsewhere – and just like that, this tenuous thread in the fraying tapestry of Japan’s theatrical tradition fully unravels.

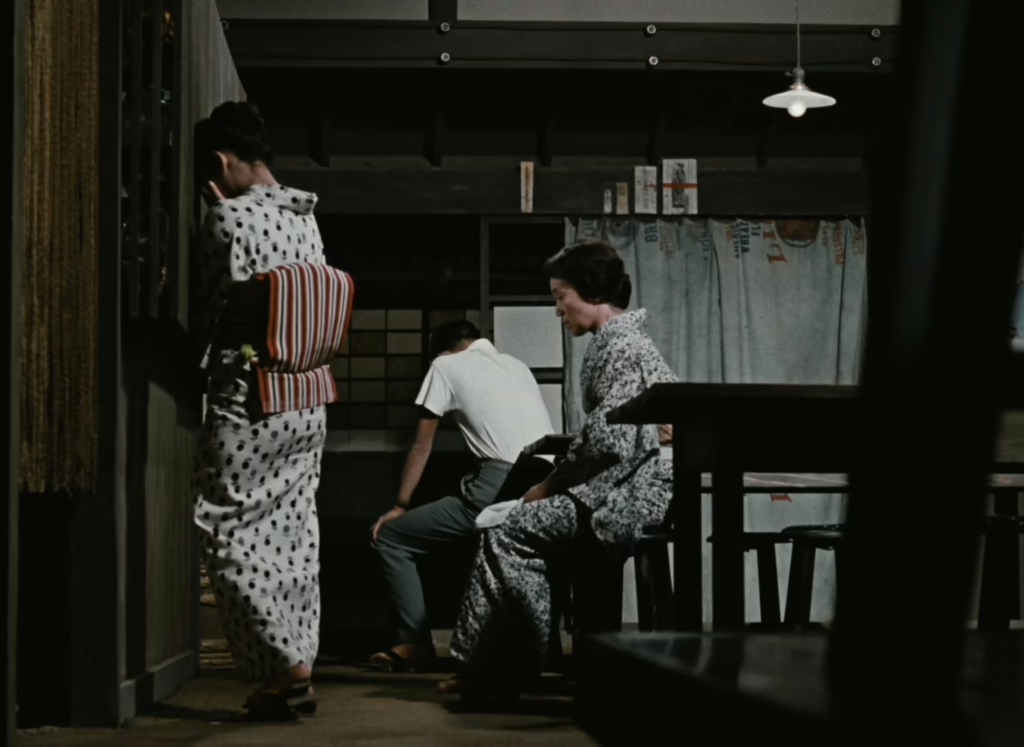

When Kiyoshi and Otaka also decide to make a brief, unannounced getaway, Komajuro is left truly defeated. “Please, tell him the whole truth,” Kiyoshi’s mother implores, inviting the possibility of a life where they can all live peacefully together. Nevertheless, any hope for harmony is rapidly dashed when the lovers return home and meet Komajuro’s violent, impulsive reaction. Defending himself from a beating, Kiyoshi pushes his father to the floor, and the low angle that follows renders him feeble indeed beneath the young man’s commanding stature. This is a world that no longer bends to Komajuro’s will, and even when Oyoshi finally reveals the true nature of their relationship, little can be done to mend the widening rift.

“I don’t need a father,” Kiyoshi asserts in a furious daze before storming out, and Komajuro does not wait around to bid a proper farewell. By the time Kiyoshi regrets his harsh words a few moments later, his father has already left, leaving behind a household whose fragmentation manifests in Ozu’s sombre, staggered blocking.

Night envelops the station where Komajuro waits for his ride out of town, and where he ultimately makes unlikely amends with Sumiko. “Shall we give it one more try?” he tentatively proposes. “Yes, we’ll work it out,” she responds, before pouring him a shot of sake. As the train pulls away into the darkness and its rear lights recede from view, Ozu extends his visual symbolism to the very final shot, joining these weathered souls in dignified surrender to the unrelenting passage of time. Their reconciliation may be modest, but in Ozu’s ephemeral, luminous world, even floating weeds find tender moments of grace.

Floating Weeds is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.