Claire Denis | 1hr 32min

Somewhere in the brown, arid plains of Djibouti, a section of the French Foreign Legion undertakes rigorous training rituals. Low angles capture their bare bodies moving in balletic unison against clear blue skies, methodically merging sensuality and discipline, while elsewhere their perseverance guides them through gruelling obstacle courses. Claire Denis’ camera matches their concentration as it absorbs the repetition of these motions, joining in the collective meditation as it drifts through the small platoon, and examines their physique in reverent admiration.

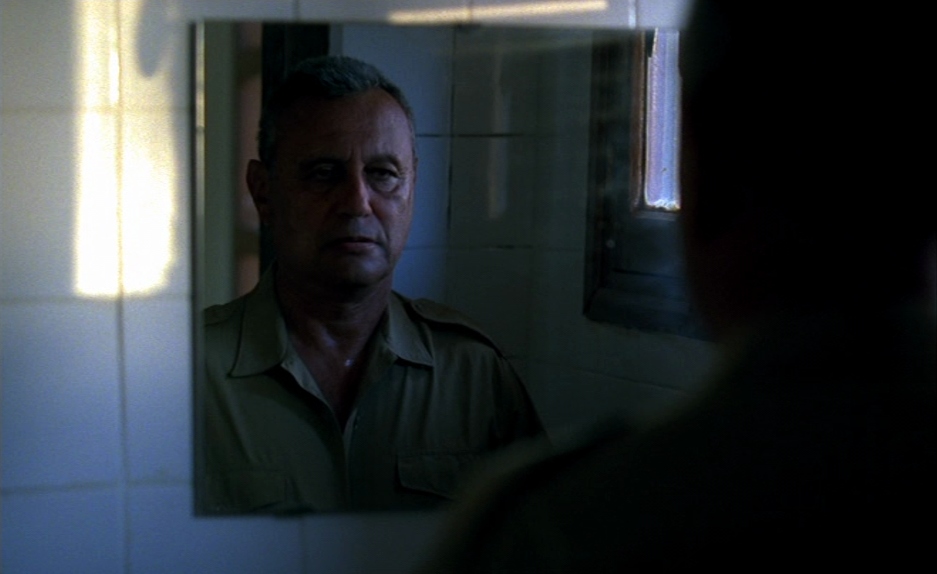

The opera which underscores these militaristic procedures lends them an enormous gravity, though it also couldn’t set a greater contrast against the electronic music of the night club, where the native Djiboutians energetically dance to their own beat against colourful, blinking lights. To these locals, the legionnaires are anomalies in a foreign environment, distantly observed with indifference and amusement – though their perspectives are not at the centre of Beau Travail. Through the eyes of our narrator Adjudant-Chef Galoup, a far more homoerotic lens is applied, weaving his memories into the fragmented framework of Denis’ postcolonial tone poem. At odds with his outward displays of masculinity is a contemptuous envy that is not only expressed through reflective voiceovers, but infused within the camera’s obsessive gaze, focused particularly around one handsome recruit, Gilles Sentain.

Although Galoup is dating a local Djiboutian woman, it is telling that he dedicates so little of his story to their dispassionate relationship. “I felt something vague and menacing take hold of me,” he contemplates not long after Sentain joins the Legion, immediately beginning a far more intense fixation fuelled by attraction and resentment. This young man does not seek to make waves, but after proving his heroism during a fatal helicopter accident, the respect he wins from Commandant Forestier officially marks him as Galoup’s rival. After all, for our protagonist there is no greater mission than “loving one’s superior, obeying him,” – a calling which very nearly confesses his repressed feelings towards this paragon of masculine stoicism, whose fatherly approval would be the ultimate recognition.

“He knew I was a perfect legionnaire… and he didn’t give a damn.”

Fortunately, Beau Travail is not interested in laying out these relationships in such plain terms. The strength of this screenplay lies in its subtext, edging Galoup towards profound self-awareness of his desires and insecurities, yet keeping those psychosexual truths just out of reach. His characterisation is certainly helped along by Beau Travail’s long stretches of wordless storytelling too, splicing in present-day scenes where this decommissioned soldier wanders Marseille without direction, and shedding the retrospective light of regret upon the past. While serving Djibouti with his Legion, he was no doubt an outsider among outsiders, yet even back home this alienation follows him wherever he goes. All that he can really hang onto are familiar military chores, his gun, and those jaded memories of complete, ideological conviction.

Clearly order and discipline are crucial to Galoup’s identity, not only grounding the motif of ritualistic military drills in his subjective recollections, but even threading the spatial repetition of homogenous visual elements through Denis’ mise-en-scène. Even in the starkest of scenes, rigid patterns frequently emerge in her blocking, mirroring the actions of men ironing their uniforms and later forming a grid of concrete graves at a funeral.

Here, the regimented structures of the military are evocatively represented, despite coming at the cost of individual identity. For Galoup, this means subscribing to a specific model of masculinity which uses violence as a means of expression, though he also wields it against the troops to override racial alliances. When one Black soldier Combe is caught deserting his post to relieve himself, his punishment to dig a hole in the scorching heat is blatantly excessive, and Galoup promptly shuts down the help that his similarly dark-skinned friends offer. “You’re not African anymore. You’re a legionnaire now,” he bitterly declares, encouraging them to abandon their ethnic identity and be absorbed into a colonial collective.

Of course, this injustice was only ever a trap for the righteous Sentain, who Galoup knows will take a stand. Provoked into assaulting his superior, he is thus sent in the desert with nothing but a compass, albeit one which Galoup previously tampered with to complicate his journey back. The Adjudant-Chef’s vengeance is complete, cruelly condemning Sentain to the same hollow solitude he knows too well – a life adrift, wandering through the emotional wasteland that has long defined his own existence. Denis’ location shooting excels in the vast expanse of salt flats that the legionnaire tries to navigate here, refusing him fresh water, and denying any shelter besides the feeble shade cast by his coat.

If Galoup’s account can be trusted, then Sentain was eventually rescued by local Djiboutians – but why would we? As far as the Legion is concerned, he was never seen again, presumed to have either died or disappeared. There is especially no reason for Galoup to believe that Sentain might have survived besides assuaging his own guilty conscience, and Denis even suggests as much by ending his presumed retrieval from the desert with a dreamy fade to white, before transitioning to a present-day Galoup lying in bed.

The consequences of his actions are not just psychological, but institutional as well, discharging him from the Legion and thus stripping him of the identity he once clung to. Still, the subjectivity of Galoup’s tale persists even beyond his tormented memories, and into the perplexing final scene which diverges heavily from Denis’ stringent formal structure. After observing him lay down in bed with a handgun, we suddenly find ourselves in a dark nightclub where Galoup stands alone, smoking and swaying to Corona’s synth-pop anthem ‘Rhythm of the Night.’ When the chorus hits, Denis Lavant finally gets the chance to show off his extraordinary acrobatic prowess, flinging his body around the dancefloor as if to reconcile those graceful militaristic exercises with an inner turmoil seeking physical release.

Is this an escape from the constraints he has long imposed on himself, we wonder, or rather a post-mortem catharsis for his troubled soul? In this final, transcendent gesture, Denis delivers Galoup from the suffocating grip of order and repression, contemplating the aching beauty of a body in motion one last time. By surrendering to its organic rhythms, Beau Travail subtly evokes a new kind of liberation discovered within the raw, unfiltered language of movement – fleeting, ecstatic, and born from a rare moment of sincere self-reckoning.

Beau Travail is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and available to rent or buy on Apple TV.