Yasujirō Ozu | 2hr 25min

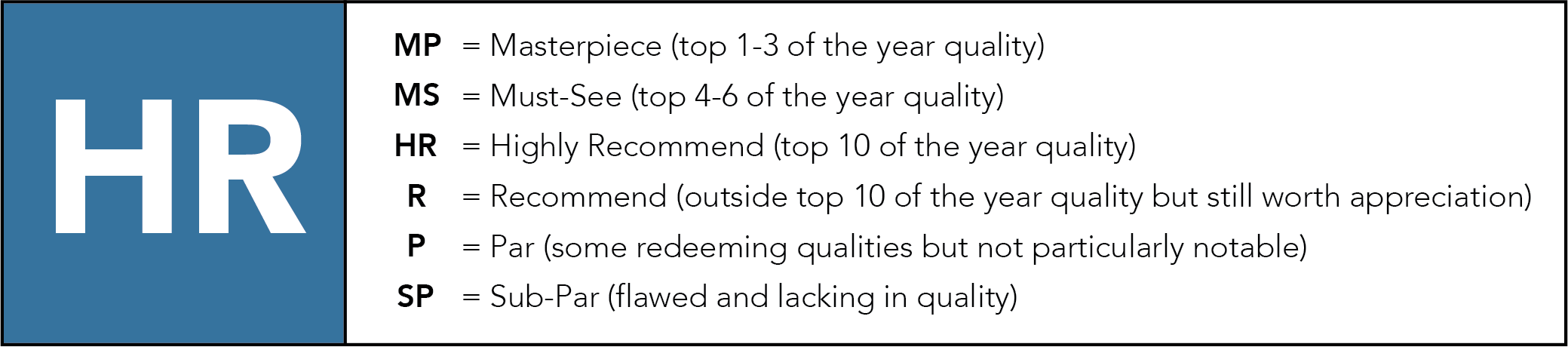

White-collar salaryman Shōji has lived his entire life abiding by the same routine as every other Tokyo office worker. In the alley outside his home, Yasujirō Ozu sets up a shot that will soon become a recurring motif, observing neighbours step in and out of doorways to carry out their morning chores. Inside, his wife urges him out of bed, and not long after he joins the 340,000 other bureaucrats crowding train platforms and marching in unison towards the city. Throughout the rest of Early Spring too, Ozu continues to build his disciplined blocking and pacing upon this mechanical order, systematically ensuring that every actor has their place in homes, offices, and bars.

When a hiking trip among office friends draws Shōji closer to his wide-eyed coworker Goldfish, the rhythm of his daily life begins to crack, and the temptation to pursue an affair takes root. Small talk flows as they walk together, and soon turns playful when they hitch a ride on a passing truck. The flame has been lit, and from there they nurture their secret romance in lunch breaks and brief retreats – though not without stirring whispers among their colleagues. Within Early Spring’s perfectly composed reflection of 1950s Japanese society, it is a shattering disruption to the status quo, yet this melancholy meditation unfolds with quiet restraint as we navigate the subtle, woeful consequences of such intimate betrayal.

Shōji’s affair isn’t the sole reason for the emotional distance in his marriage, Ozu is sure to emphasise, but rather a symptom of repressed, deeper-seated issues. This salaryman has passively submitted to life’s mundane currents, allowing himself to be led astray in whichever direction they may flow, while Masako seeks solace with her mother who recounts stories of her own husband’s infidelity. Shōji’s service in the war surely left some unresolved trauma, though the more recent grief of losing a child also painfully lingers, deepening the layers of memory and longing in their strained relationship. Some nights he spends getting drunk with old army buddies, other nights he meets up with Goldfish, but wherever he is on the anniversary of his son’s death, his absence stings Masako just the same.

Even amid such aching melodrama, Ozu’s direction is subdued, underscoring Shōji and Masako’s estrangement by patiently intercutting across their disconnected lives. While Shōji is out, distracting himself from the morose atmosphere back home, Masako is thoroughly absorbed in it. Wide shots frame her small figure through doorways, turned away from the camera, and even that recurring alleyway outside the house begins to appear far darker and colder than usual. When she finally confronts him, Ozu alternates between isolating mid-shots, deliberately placing us right in the middle as each directs their gaze toward the camera. With the rift remaining unhealed, we leave them in separate rooms, yet still he maintains these parallel editing rhythms as they silently ruminate on guilt, heartbreak, and disillusionment.

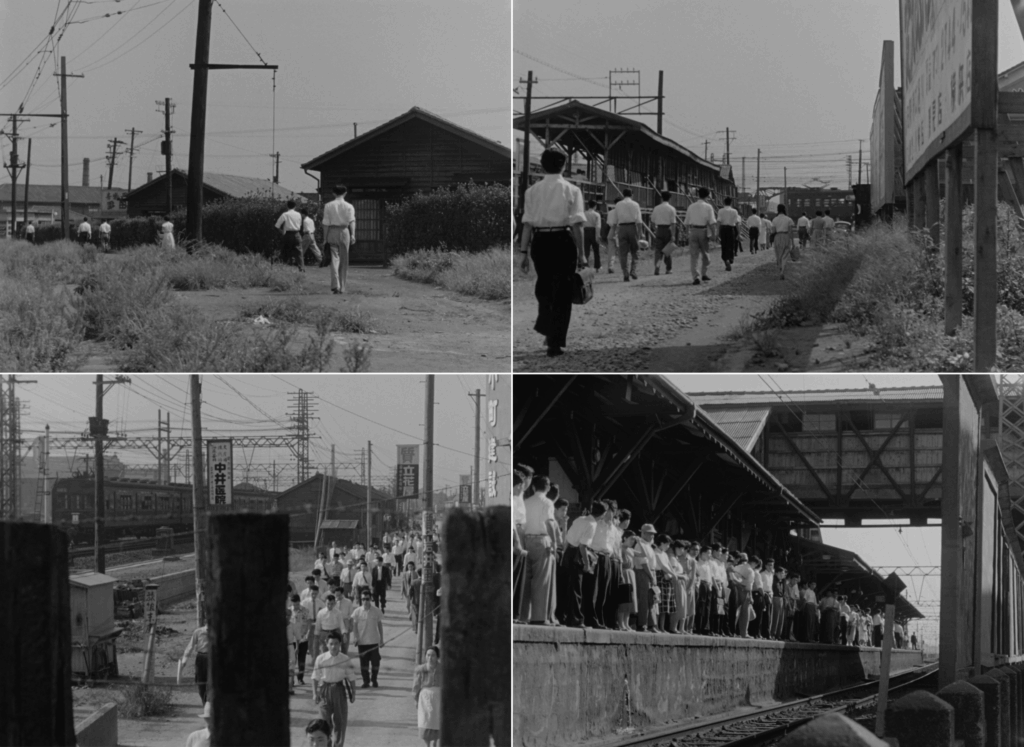

Even as we dwell in the private affairs of the Sugiyama home, Ozu formally threads in glimpses of the larger urban landscape, where trains slip through industrial neighbourhoods and neon lights blink against the night sky. Pillow shots and cutaways serve as visual punctuation in Early Spring, even pausing on an electric fan during Shōji and Goldfish’s first kiss to let the soft hum of modern world seep into their private moment. Within this broader context, Ozu also compares Shōji’s struggles to those of others, relating his child’s passing to a young neighbour’s anxiety over an unexpected pregnancy. He should count himself lucky for having a baby at all, Shōji insists, though his hypocrisy is exposed when he also disregards the dying words of a former coworker urging him to appreciate his ordinary life.

Only when the company’s talk of temporarily relocating Shōji becomes a tangible reality does he begin to understand the mundane privilege he has taken for granted, and how fragile it really is. Surely he is only moving to end their affair, Goldfish bitterly assumes, before ultimately deciding to attend his farewell party and part on tearful, amicable terms. Ozu handsomely arranges sake bottles through the shot here as the team sings ‘Auld Lang Syne’, though as Shōji packs up his belongings at home, his mess of papers and books underscore an even deeper disarray. Masako does not intend to leave with him, we learn – this is to be a completely blank slate for our uprooted salaryman.

The dress which hangs on a door in his provincial Mitsuishi home merely passes by in Ozu’s cutaways, but the absence it implies is quietly devastating. Nevertheless, he is a storyteller who would much rather offer redemption through growth than deny his characters a second chance, tenderly framing Masako’s return as an act of resilient grace. In true Ozu style, their reconciliation is understated, restoring warmth through the gentle reassurance that “Three years will pass quickly” – and indeed, time continues its steady flow through his transient pillow shots. Scenes of smokestacks and steam trains settle into Early Spring once more, reaffirming the muted endurance of a marriage that has weathered grief, betrayal, and silence, and now, at last, begins again.

Early Spring is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.