Kogonada | 2h 19m

When David picks up a hired car for an out-of-town wedding one weekend, the near-empty warehouse he arrives at is not quite the rental depot he was expecting. Standing before a small panel consisting of the German-accented ‘Cashier’ and the older ‘Mechanic’, the process feels more like an audition than anything, with a camera set up and a headshot somehow on file. “I’m not an actor,” David insists. “Sometimes we have to perform to get to the truth,” they cryptically respond, before sending him on his way.

If Shakespeare is to be believed, then all the world is a stage, and A Big Bold Beautiful Journey indeed understands the roles one must play to uncover the truths we hide from ourselves. When David meets Sarah at the wedding and their hired GPS devices remarkably conspire to send them down a shared path of old memories, reality itself seems to bend, blurring and reassembling identities as fluidly as costume changes. That both also happened to be theatre kids in their youth only deepens the metaphor at play, beckoning each towards more idealistic versions of themselves that have been lost to time, yet which now re-emerge in metaphysical rehearsal spaces from the past.

Now on his third feature, Kogonada’s meditations on memory, family, and grief continue to develop through soothing formal rhythms, resisting melodrama where subdued studies of human connection offer richer resonance. Pivoting from the warm drama of Columbus and After Yang’s psychological science-fiction, romantic fantasy becomes his chosen genre in A Big Bold Beautiful Journey, drawing distinctly from the dreamy melancholia of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. The screenplay does not possess the same sharp edge as Charlie Kaufman’s autopsy of a broken relationship, often embracing sentimentality over cerebral acuity, yet Kogonada nevertheless channels immense imagination through the sincerity of this sweet, introspective odyssey.

Even before we enter the doors to David and Sarah’s pasts, Kogonada is already building out this whimsical world through bright colours and soft lighting, attuning us to the sensitivities of their lonely lives. The black, orange, and transparent umbrellas which decorate the wedding where their eyes first meet offer modest protection from the rain, evoking Jacques Demy’s visual symbolism in The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, and even adopting a similarly lush score of flutes, strings, and piano. With its propulsive arpeggios and wandering melodies, Joe Hisaishi’s first Hollywood score is a marvel, and only ever let down by the irregular needle drops that break up the musical throughline.

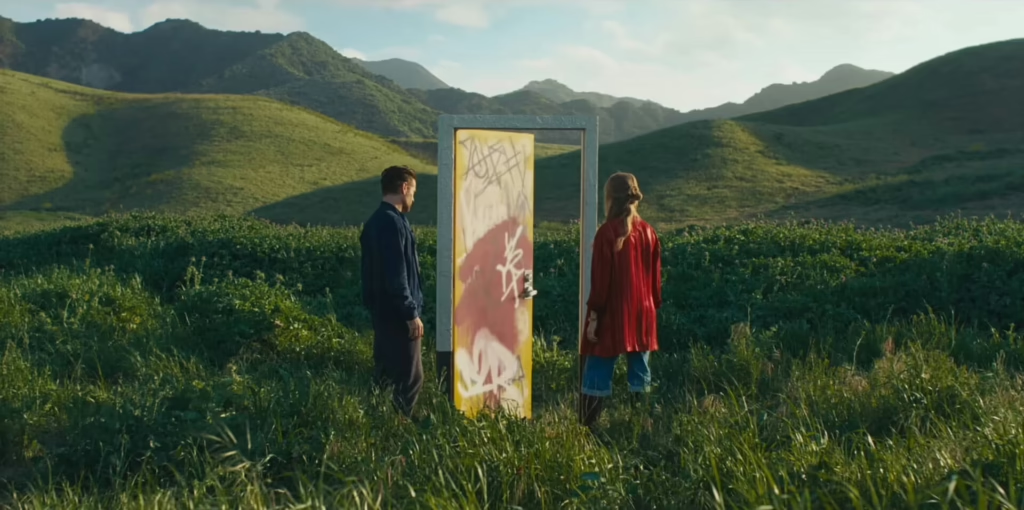

In the costume designs too, Kogonada continues to establish these characters as isolated inverses of each other – David often dressed in melancholy blues, Sarah in dazzling reds, and both adopting pieces of each other’s palette as their worlds progressively merge. They may be separated by the windows of their adjacent hotel rooms early on, yet both carry unresolved baggage, largely stemming from romantic relationships and parental distance. Only when they are mysteriously led to an arched, red door standing in the middle of a forest does Sarah escape her own bubble, admiring the lighthouse view he holds in his heart, while he later ardently explores the museum she frequented with her mother.

Each stop along this road trip effectively reveals its own self-contained world, seemingly projected straight from their minds and populated by figures they have not seen in many years. More than simply observing these recollections though, the adventurers tread a narrow boundary between reliving and shaping them, trying to mend old mistakes with mixed results. As David steps back into the lead role of his high school musical, he desperately grapples with the teenage rejection that has haunted him ever since, while an entirely manufactured memory taunts Sarah with the guilt of not being by her mother’s side when she passed away. At the same time though, the very act of sharing such personal impressions allows a new type of catharsis neither has discovered before, born not from resolution, but recognition.

After all, David ponders, isn’t love simply the sharing of a single life? These worlds are not so much memories as they are emotional states, abstractions of longing, and imagined what-ifs, and the opportunity to glimpse another’s true essence right from the start may very well lay the foundation of mutual understanding. Through Kogonada’s editing and staging, visual continuity seamlessly erodes, revealing a dreamlike instability that bends to his characters’ fears and desires. In one specific restaurant where both David and Sarah happened to break up with their partners, the intercutting between their respective tables even slyly converges their stories, until we find all four sitting across from each other.

Eventually, identity also proves to be malleable in this realm of theatrical illusion. If we were to raise ourselves, Kogonada ponders, what might we do differently than our parents? What were their personal struggles that we took for granted as children, and if we were to spend one more night in their tender care, what comfort or advice would we seek? A Big Bold Beautiful Journey bears no great epiphany besides the acceptance of happiness into one’s life, yet the totality of its ethereal, impressionistic world nevertheless washes over us like a wave of nostalgic wonder, illuminating forgotten scenes of these lovers’ lives. As they finally step out of rehearsal, Kogonada too returns to life’s stage, delicately revealing the self-determined joy that comes from nowhere but our own, immediate choices – if only we take on the role of the person we’re ready to become.

A Big Bold Beautiful Journey is currently playing in cinemas.