Ari Aster | 2hr 29min

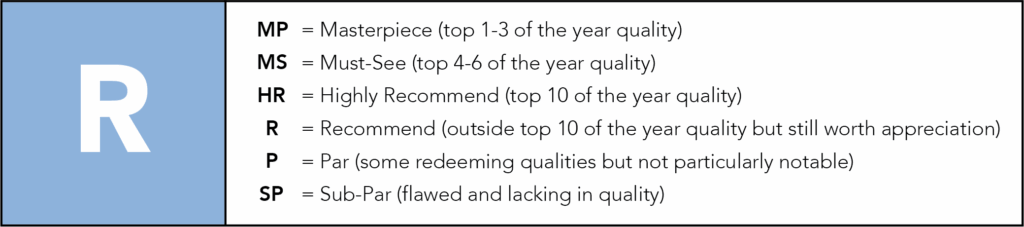

Sheriff Joe Cross does not appear to be a particularly dangerous man in Eddington. He may belong on the more conservative end of the political spectrum, denouncing COVID-19 mask mandates and asserting police authority during Black Lives Matter protests, but his ineffectiveness in both public and private life is also clear. Especially next to Mayor Ted Garcia, he recedes into an uncharismatic emblem of old-fashioned masculinity, deciding to run for office yet failing to rally the support which that beloved, progressive politician effortlessly whips up among locals. Plastered across the buildings of this rural town, Ted’s election posters bear giant, beaming smiles, while Joe physically shrinks beneath them in palpable discomfort.

When this embittered sheriff’s misfortunes consequently reach a breaking point midway through Eddington, Ari Aster’s sweeping narrative takes a shockingly dark turn. There is a malevolence in Joe which we severely underestimated, transforming him from a comically tragic figure – not unlike Joaquin Phoenix’s usual roles of late – into a chilling embodiment of paranoid authoritarianism.

The ‘woke’ protestors who Aster lightly mocks may be misguided in their attempts to instigate social justice, but this is not a story of parallel evils. Even when Eddington submits to the right-wing fantasy of one man standing against an army of violent terrorists, its satirical target is blatantly apparent, dismantling the delusional bravado embedded in modern American mythology. What initially begins as a portrait of impotence here gradually reveals itself as a study in reactionary control, and those ideological narratives which legitimise it. Naïve idealism might falter in this twisted reflection of recent history, but self-aggrandising power fatally corrodes.

Eddington does not waver from the trajectory of Aster’s career thus far, leaving behind the pure horror of Hereditary and Midsommar, and embracing psychologically distorted mirror worlds one step away from our own. Where Beau is Afraid dove in the deep end of one man’s anxious self-loathing, Aster instead anchors Eddington to May 2020, during the tumultuous early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Traces of Robert Altman’s Nashville can be found in the idiosyncratic ensemble which makes up this Southwestern town, exposing the politics that hide in every corner of mundane life, though Aster uses a global health crisis to stoke its simmering tensions rather than a country music festival. The result is thematically ambitious, capturing a microcosm of America’s fractured political landscape, creeping religious extremism, and digitally mediated existence, but there is nevertheless a formal lack of focus here which struggles to handle the combustible chaos waiting to be lit.

It is a rocky road that Aster has traversed once before in the expansive, metaphysical odyssey of Beau is Afraid, though without the same dedication to motifs which effectively tie its looser elements together. In comparison, Eddington tends to wander, sacrificing tension in subplots concerning a fringe cult and viral conspiracy theories that only intermittently surface. At the very least, each still play a part in Aster’s patchwork tapestry, obliquely illustrating a declining, disillusioned nation.

With Eddington’s lone lawmen, frontier justice, and desert landscapes as well, what better genre is there to reveal the rot in America’s heartland than the Western? Composer Bobby Krlic evidently understands the task at hand in his dissonant, off-kilter callbacks to Ennio Morricone’s musical cues, tensely underscoring stand-offs in the town’s main street where asphalt replaces dirt, and assault rifles supplant pistols. In tense wide shots too, Aster visually places physical distance between Joe and Ted as they verbally spar, transforming these classic archetypes into subjects of political theatre. With the sheriff’s posturing and the mayor’s virtue signalling, neither seem entirely adept at running the town, but their rivalry nonetheless locks them in a performative struggle for control.

The collateral damage of this conflict is ravaging, though not always necessarily fatal. Among the first of its victims is Louise, Joe’s anxious, reclusive wife, played by a gaunt-faced Emma Stone with deep mental scars. Living almost entirely behind closed doors, she spends her days sewing creepy dolls to decorate their home, and longing for connection beyond her preoccupied husband and overbearing mother. Although Joe occupies his free time watching YouTube videos on ‘How to Convince Your Husband or Wife to Have a Baby [5 STEPS!]’, he completely neglects to inform Louise of his intention to run for mayoral office before publicly launching his campaign, leaving her wounded and betrayed. Even worse, she is rendered a political pawn in his attempt to smear Ted with allegations of sexual assault, not only forcing her secrets out into the open but misrepresenting them in the process.

As grim as Eddington gets in its grappling with real traumas and events, Aster holds his darkly comedic ground, capturing all-white crowds protesting institutional racism and attempting to bring progressive ideologies home to close-minded parents. Their cause is not trivialised so much as detached from the motives of individual characters, at least one of whom joins purely to get closer to his crush, Sarah. That the woefully infatuated Brian should flip so easily and become a conservative influencer when given the opportunity amusingly reveals the moral vacancy at his core, drawing an especially pointed allusion to the viral elevation of teen vigilante Kyle Rittenhouse. Meanwhile, the romantic drama that entangles Sarah, Ted’s son, and the town’s only Black cop Michael further muddies the waters of identity politics, becoming a lightning rod for Joe’s ambitions in his self-serving climb to the top.

With long tracking shots sinking us into the sheriff’s unravelling psyche, it is easy to lose ourselves in Eddington’s polarised tensions and overlook the third power at play, insidiously nudging everyone towards mutually assured destruction. The tech industry’s influence is woven into the fabric of the narrative, propagating misinformation and manipulating police investigations, but its encroaching presence is also subtly present in the development of a hyperscale data centre just outside of town. Few residents are particularly supportive of its development, especially given the land ownership dispute between Native Americans and local authorities, yet the project continues to quietly progress as more explosive conflicts dominate the public eye. Its growth is passive but persistent, reshaping the entire town while everyone else is too distracted to notice – right up until its construction is finished, inescapably looming in Eddington’s final shot.

For a man whose greatest fear was always loss of control, Joe’s fate is almost poetic in its cruelty, thrusting him into the feeble, helpless state he has spent his life trying to avoid. As diffuse as Aster’s storytelling may be at times, he is always cognisant of the threat which turns fragile men into dangerous myths. America’s faceless institutions of power are much larger than any one individual, and in Eddington, they do not distinguish between idealists or opportunists – only those who serve the narrative, and those who are sacrificed to sustain it.

Eddington is currently playing in cinemas.

Pingback: The 10 Best Screenwriters of the Last Decade