Danny Boyle | 1hr 55min

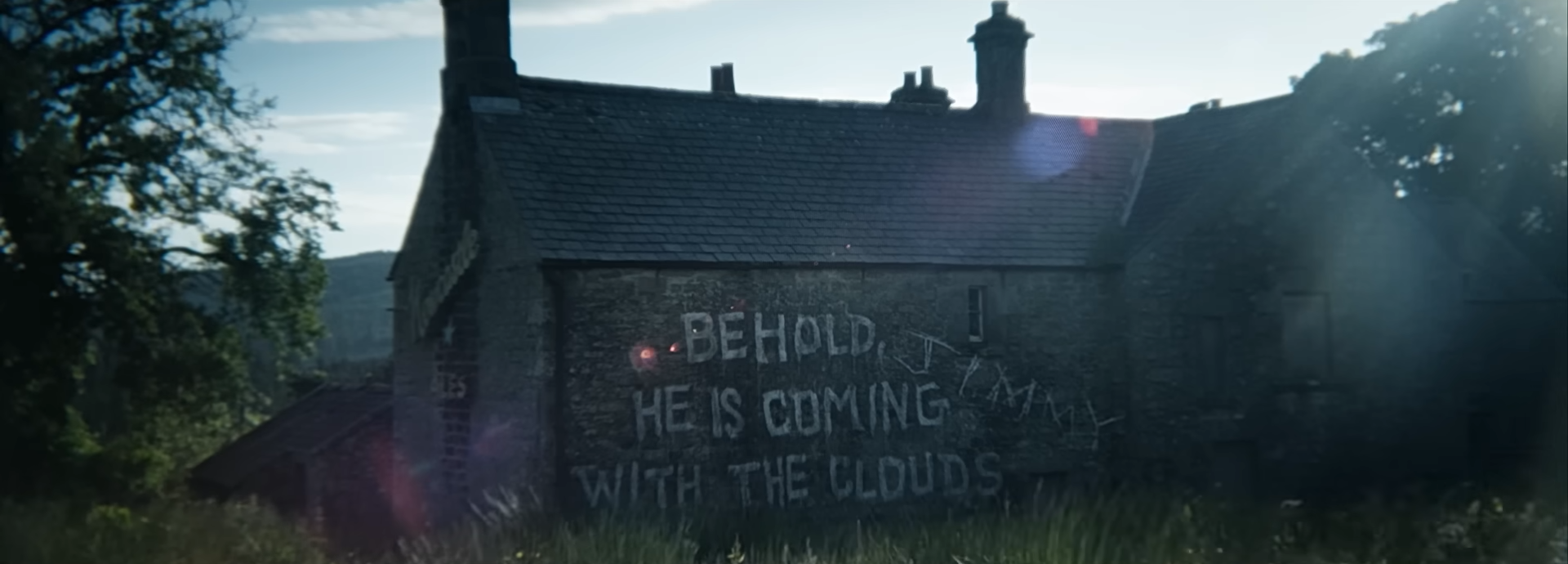

The reports at the end of 28 Days Later suggesting that the ‘infected’ would soon die of starvation were wrong. These zombie-like creatures are no longer simply people driven to their most primal, aggressive instincts by the Rage Virus – they have effectively evolved into their own species by the time we join Lindisfarne’s remote island community in 28 Years Later, feeding off worms when more warm-blooded food sources are scarce. Extraordinarily, there even seem to be signs of culture developing among them, with rituals, family units, and social hierarchies giving structure to their otherwise chaotic existences. It is enough to make an observer pause in wonder at the sheer persistence of life, though not for so long that one might hang around and risk their own.

Danny Boyle’s return to the horror series which redefined the zombie genre is very welcome, shifting back to his cinematic strengths that were absent in the disappointingly milquetoast Yesterday. This is a filmmaker whose passion bleeds from his craftsmanship, building upon the gritty kineticism of the digital camcorders he experimented with in 28 Days Later, and turning to iPhones as the main tool to recapture that raw immediacy. Lightweight film technology has improved vastly since then, now allowing for a higher-resolution image, yet 12-year-old Spike’s journey to the perilous mainland is nevertheless well-served by this handheld, guerilla-style shooting. Through his coming-of-age, he must confront a broken world stripped of its humanity, but in that visceral chaos 28 Years Later also uncovers a melancholy beauty that so many survivors stubbornly reject.

Local scavenger Jamie has no reason to suspect that a father-son hunting trip to the infested mainland would inspire Spike to run away from home, but upon discovering his dad’s lies and selfishness, that is exactly what he does. His mother Isla has been sick for some time, and whispers of a reclusive doctor spark his desperate hope, so the young boy ultimately sees no other option than to seek him out with her in tow. Intercut with his initial departure are newsreels and clips of wars from throughout history, often featuring children marching in military units, and drawing parallels to his own abrupt transition into adulthood. Boyle does not rely heavily on any musical score here, but rather a passage read from Rudyard Kipling’s haunting poem Boots, transposing the bleak thoughts of a Second Boer War infantryman onto Spike’s expedition. Through the sheer force of repetition, the maddening, hypnotic monotony of the battlefield rises to a panicked urgency, yet never changes its relentless rhythm.

“(Boots—boots—boots—boots—movin’ up and down again!)

There’s no discharge in the war!

Don’t—don’t—don’t—don’t—look at what’s in front of you.

(Boots—boots—boots—boots—movin’ up an’ down again);

Men—men—men—men—men go mad with watchin’ em,

An’ there’s no discharge in the war!”

‘Boots’, Rudyard Kipling (1903)

This entire section may very well be the cinematic peak of 28 Years Later. Boyle’s bullet time effect is established here when the infected are killed, freezing the action as the camera rapidly hurtles through space around them, and jump cuts also imbue the action with a grating abrasiveness. Unfortunately, he doesn’t follow through on everything that he sets up, eventually repurposing the use of infrared filters from horrifying cutaways to dream sequences before dropping them altogether. The overall stylistic coherence is somewhat questionable, especially given the handful of other offhand embellishments that aren’t revisited at all, but the film’s dramatic angles and abrasive editing continue to flourish even when his erratic swings falter.

Boyle is often far more appreciated for his dynamic pacing than his mise-en-scène, and yet the cinematography of 28 Years Later still finds a wondrous beauty in the natural world, striking haunting silhouettes against the sky and revelling in its surreal aurora borealis. When Spike eventually reaches his destination and meets the elusive Dr Kelson, Boyle also delivers what may be the film’s defining set piece, revealing a forest of bone pillars constructed around a soaring tower of skulls. It is called Memento Mori, the doctor explains, Latin for “Remember you must die.” The sight of this macabre art installation may stoke fear from a distance, yet it also becomes the channel through which Dr Kelson expresses his immense respect for all life, incorporating the remains of infected and uninfected alike – “because they are alike,” he insists.

Ralph Fiennes is remarkably well-cast in this relatively small role, embodying a gentle eccentricity that has been deprived of human contact for many years, but which has made peace with things no one else dares face. He stands at the centre of the film’s entire ethos, nudging Spike forward in his journey to confront death with grace, birth with tenderness, and transformation with courage. Through the three characters who represent each, Boyle constructs an unusual trinity, echoing those natural rhythms of existence that persist in a world that has seemingly destroyed them.

As Spike reaches this milestone in his maturation, fires and memories intertwine through an ethereal montage set around the Memento Mori shrine, now illuminated as an icon of extraordinary hope and reverence. For all its pulpy violence and bloody horror, 28 Years Later is also surprisingly soulful in its lyrical contemplations, asserting a belief in the soul that transcends whatever version of humanity we abide by. With various references to a mysterious “Jimmy” scattered all throughout this film, the stage is set for an intriguing sequel which Boyle is unfortunately not returning to the director’s chair for, instead passing the considerable responsibility to Nia DaCosta. Regardless of where that future instalment goes though, Boyle’s return to his beloved, existential franchise stands as a fierce act of anthropological curiosity, not so much questioning if humanity can be saved than whether it is still worth defining.

28 Years Later is currently playing in theatres.