Akira Kurosawa | 2hr 2min

The covert, labyrinthine path through Tokyo’s seedy underbelly that police officer Murakami follows in Stray Dog is a strenuous enough journey on its own, even without considering the sweltering heatwave bearing down on the city. That this quest to recover his stolen pistol lands right in the middle of summer only makes it that much more exacting, dialling up the pressure to find the man who has bought it off the black market, and is now using it to commit a string of crimes. While the rest of the city is watching baseball games and relaxing, both sides of the law remain restless in their isolated pursuits, drawing ever closer under Akira Kurosawa’s sharp, observant gaze.

Handheld and electric fans are constant motifs here, cooling down those desperately trying to escape the heat, though the crowded blocking doesn’t help to ease the discomfort. When Murakami descends into the decadent nightclubs of Tokyo, Josef von Sternberg’s influence emerges in Kurosawa’s cluttering of the frame, filled with lights, smoke, décor, and bodies dripping with sweat. This is a world inhabited by illicit arms dealers and violent gangsters, and if Murakami is to find this disturbed gunman, he must fully immerse himself in its sleazy, lawless decadence.

Kurosawa’s methodical approach to unravelling this investigation is a stepping stone towards the sprawling procedural he would later conduct in High and Low, yet Stray Dog nevertheless remains an immense accomplishment in his early career. Tokyo takes on vibrant textures as Murakami navigates its streets and buildings, giving way to marvellously edited montages of a city scrutinised beneath his watchful eyes in a double exposure effect, and traversed in patient tracking shots. The visual storytelling is tremendous as he tails the pickpocket for several days, wearing her down until she points him towards Honda, the notorious gunrunner she sold his weapon to.

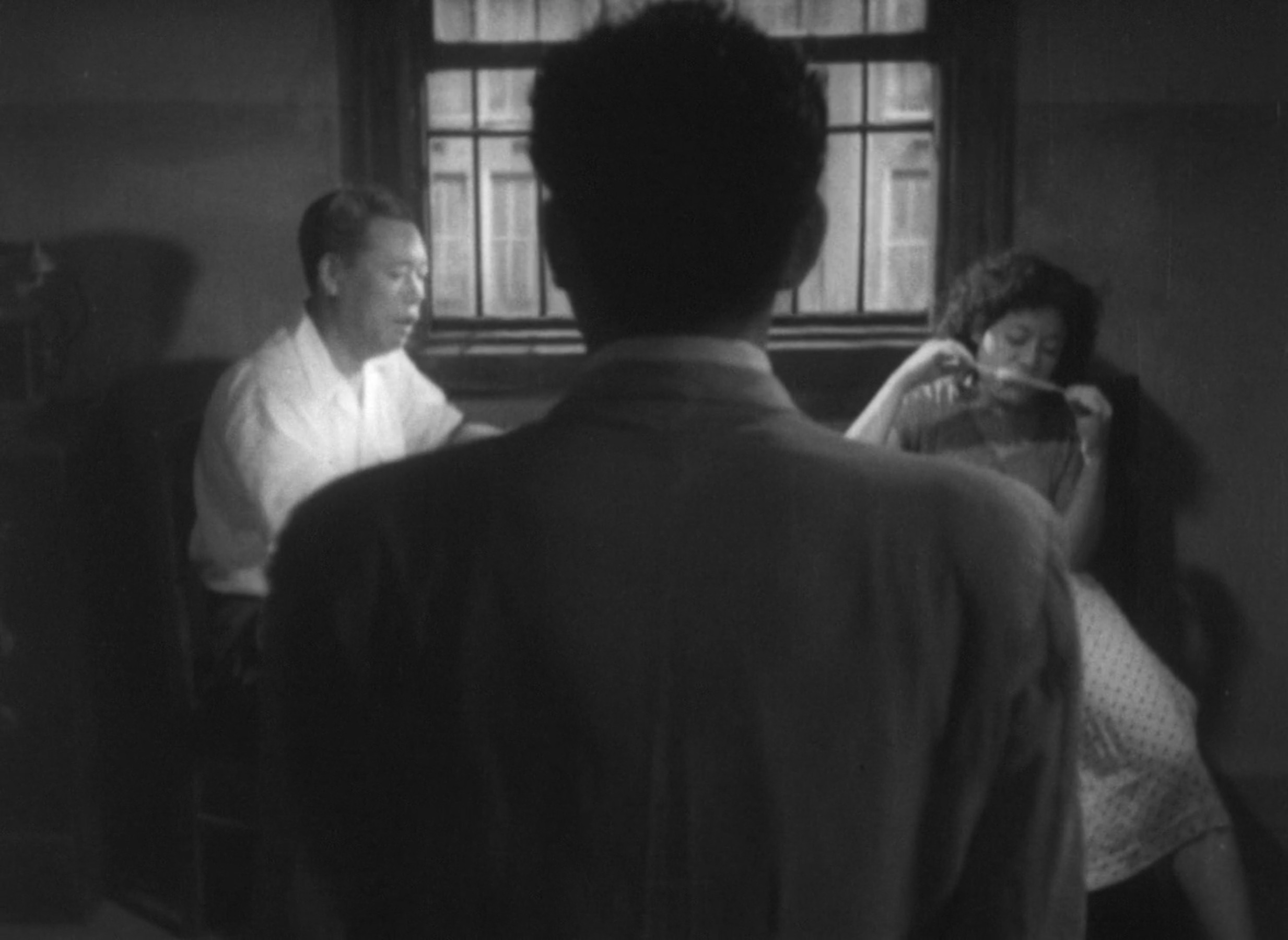

When Honda’s girlfriend is taken in for questioning, she proves much tougher to break, and so the arrival of veteran detective Satō is timely indeed. In his playbook, charm is a far greater tool than intimidation, casually winning her over with ice blocks and cigarettes. In one superbly blocked composition, Kurosawa mirrors this new hierarchy too by pushing Murakami behind his older colleague, and foregrounding the girlfriend’s guilty profile as Satō interrogates her.

The buddy cop dynamic which emerges here would later set the stage for David Fincher’s Se7en, similarly playing on the contrast between a fresh-faced detective and his older, wiser companion. Kurosawa’s casting of the highly-strung Toshiro Mifune and unflappable Takashi Shimura is incredibly inspired here, drawing an ideological divide which separates those younger generations directly affected by the traumas of World War II from those whose views are rooted in Japan’s traditional, stoic values. The more that both learn about their target Yusa, the more the cops’ differences come to light as well, making for a compelling discussion one night when Satō invites Murakami over for drinks.

“They say there’s no such thing as a bad man. Only bad situations,” Murakami deliberates, reflecting on the disturbed diary entries they found in Yusa’s shabby, filthy home earlier that day. Men become monsters in war, he believes, warped by inhuman orders from a government that neglects them as soon as they return home. He is not surprised that such a man has now fallen in with the yakuza, though seeing how this sort of nuance wracks Murakami with self-doubt, Satō is not so forgiving. “You can’t be this tense all the time if you want to be a cop,” he responds. War may have turned Yusa into a wild, untamed beast, but now that this monster is loose in society with a gun, it is up to them to capture him. “A mad dog sees only straight paths. Yusa sees only straight paths now,” Satō expounds, clinically reasoning that the only way to get to him is through his girlfriend.

“He’s in love with Harumi Namiki. She’s the only thing he sees.”

When applied to Murakami as well, this metaphor continues to ring true. He is blinded by his focus on Yusa, which itself is fed by his guilt over losing that gun in the first place. This rookie cop acts on impulse, often heading straight into danger without backup and hoping that he might stop Yusa from wreaking further devastation across Tokyo.

It is only inevitable that the heatwave that has accompanied this investigation should eventually break, and being a master of using weather as symbolism, Kurosawa carries it out with incredible formal purpose and style. While Satō is following a lead to Yusa’s hotel, Murakami is pressing Harumi to give up her boyfriend, wearing away at the worldly bitterness which he has imparted on her. It’s the world’s fault he has resorted to theft, she asserts, while slipping into a dress he has stolen for her – yet the guilt she suppresses is too strong. As she begins to cry, the skies finally open up, and Kurosawa traps her and Murakami within a confining, melancholy frame behind the falling rain.

Meanwhile, as the distance Satō and Yusa narrows, so too does the furious deluge mark their meeting with dramatic tension. While trying to call Murakami from the hotel phone booth, Satō remains unaware of an armed Yusa standing just outside, who fearfully realises that he is a police officer. The outlaw’s attempt on his life is fortunately non-lethal, though his shoulder wound is enough to tip an inconsolable Murakami over the edge, and ultimately convince Harumi that her boyfriend must be stopped.

As our bold, young protagonist sets out on his own one last time to confront the dangerous gunman, Kurosawa displays supreme confidence in his visual storytelling. The weather has stabilised – no longer is Murakami caught in the stifling grip of a heatwave, and neither does rain douse his spirits. “Don’t panic. Calm down,” his inner voice instructs him, taking on Satō’s cool composure as he searches the train station for a 28-year-old man in a white linen suit and muddy pants. Kurosawa’s camera possesses the patience of Hitchcock as it slowly passes across a line of legs, before eventually settling on a pair of filthy shoes and tilting up to the rest of the body. His taut editing soon comes into play as well, cutting between both their faces until Yusa confirms Murakami’s suspicions by using his left hand to strike a match – and from there, the final stand begins.

Through the train yard and into a forest, Murakami daringly chases his target, though for now he holds off from shooting. He remembers exactly how many bullets were in his gun when it was stolen, and by deducing clues from each crime scene, he knows how many have been used. It is immensely satisfying seeing his sharp wits play into this set piece, and even more so knowing that it is Satō’s influence that has taught him self-control, further demonstrated in a close-up of his unshaken, bloody hand after his arm is shot. Two more wasted bullets from Yusa’s pistol, and Murakami is ready to bet his life that the barrel is now empty, rushing forward to apprehend the panicked, defenceless outlaw.

It isn’t that Murakami no longer understands Yusa’s trauma, nor that Satō completely disregards empathy, but he is right that these feelings must be put aside in their line of work. “The more you arrest them, the less sentimental you’ll feel,” he remarks – not that this pragmatism necessarily fixes the problem at the heart of a troubled society. Even with Yusa and the illicit arms dealer Honda brought to justice, Kurosawa’s cynicism lingers in his ending, acknowledging the countless disturbing cases that Murakami will continue to face throughout his career. For better or worse, this line of work allows little room for moral ambiguity, yet Murakami remains fully conscious of the bitter, underlying irony – the stray dog that finds purpose in saving lives is not so dissimilar from the one which takes them away.

Stray Dog is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.