F.W. Murnau | 1hr 28min

As far as the proud, jolly doorman of The Last Laugh is concerned, there is no greater calling in life than the hospitality he offers to patrons of the Atlantic Hotel. This is his entire identity, so essential to his being that he is not even given a name. Instead, he is distinguished by his portly figure, regal moustache, and elaborate, militaristic uniform, commanding respect from those who pass through the revolving door he loyally guards. That he is so willing to help the homeless children who loiter outside his apartment building speaks to the strength of his moral character as well, establishing him as a man whose existence has been joyfully dedicated to the service of others.

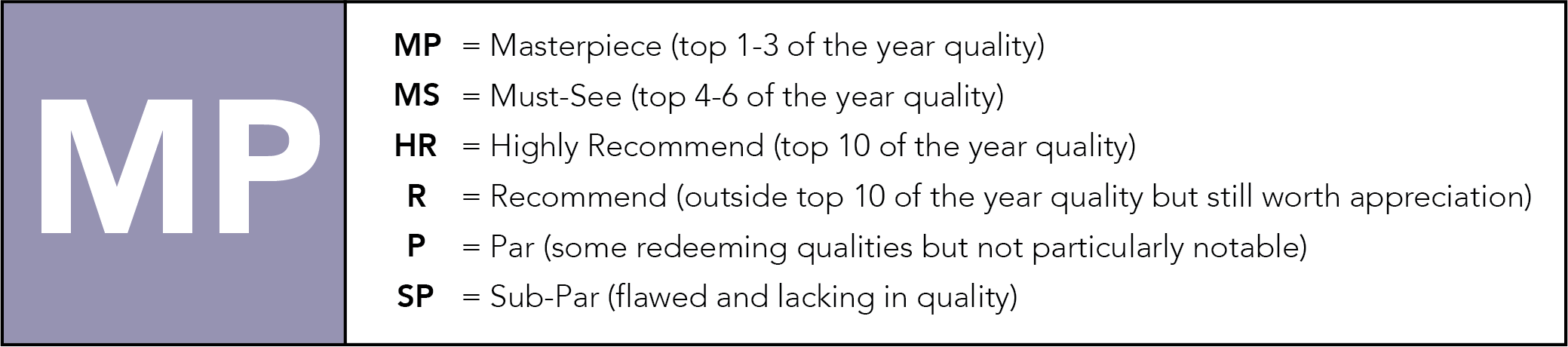

It is a cruel turn of events then which delivers a letter of demotion into his hands, relegating him to the position of washroom attendant. He has gotten too old for his position, management claims, and in his place a younger man has donned the uniform he holds in such esteem. Framed through the glass double doors of the boss’ office, darkness surrounds him on all sides, until the camera tracks forward across the barrier and into the room itself. As we read these devastating words, F.W. Murnau imprints a vision over the top of the previous attendant handing in his white coat, and the text begins to blur in tearful distress. There is a desolate future ahead of this former doorman, and from here The Last Laugh plunges into his deep humiliation, teasing out the shame and indignity that comes with an earth-shattering shift in status.

So rich is Murnau’s visual storytelling here that all exposition is minimised to a single intertitle, giving him room to explore the ambitious limits of his camerawork and mise-en-scene. Three years before Fritz Lang’s triumph of set design that was Metropolis, The Last Laugh was bringing to life busy streets, apartment buildings, and majestic hotels built on studio stages and backlots, each brimming with the sort of expressionistic detail that Germany was pioneering in the 1920s. The glass revolving door in the hotel foyer makes for a particularly impressive set detail as well, the oscillation of its vertical lines constantly reframing exterior views and merging with brisk camera movements to imbue the city with a bustling liveliness.

On a larger scale, this liberation from static tripods sits at the core of The Last Laugh’s stylistic brilliance, especially standing out for its immersion into our downtrodden doorman’s psyche. Right from the very first shot, we are introduced to the hotel from within the elevator, descending multiple stories as we gaze through the metal grills into the crowded lobby. When the doorman dances, the camera spins with him in gleeful unison, and when he dashes past sleeping security guards on the night shift, it too takes desperate flight.

Having recently dabbled in the realm of horror and fantasy, Murnau relishes the uncanny dreaminess of these visual devices, entering the doorman’s waking nightmare of the hotel’s edifice bearing down on him like a monster and later slipping into his unconscious mind with experimental panache. There, a double exposure effect blends a close-up of his sleeping face with an absurdly tall vision of the hotel’s revolving doors, before entering hazy, distorted crowds lavishing him with applause. There is no cumbersome struggle with bulky luggage in this world, as he is instead endowed with an almost superhuman strength, lifting bags with one arm above his head and tossing them into the air. For a moment, Murnau’s camerawork even goes completely handheld, stumbling with the doorman in dizzy motions among his ardent admirers.

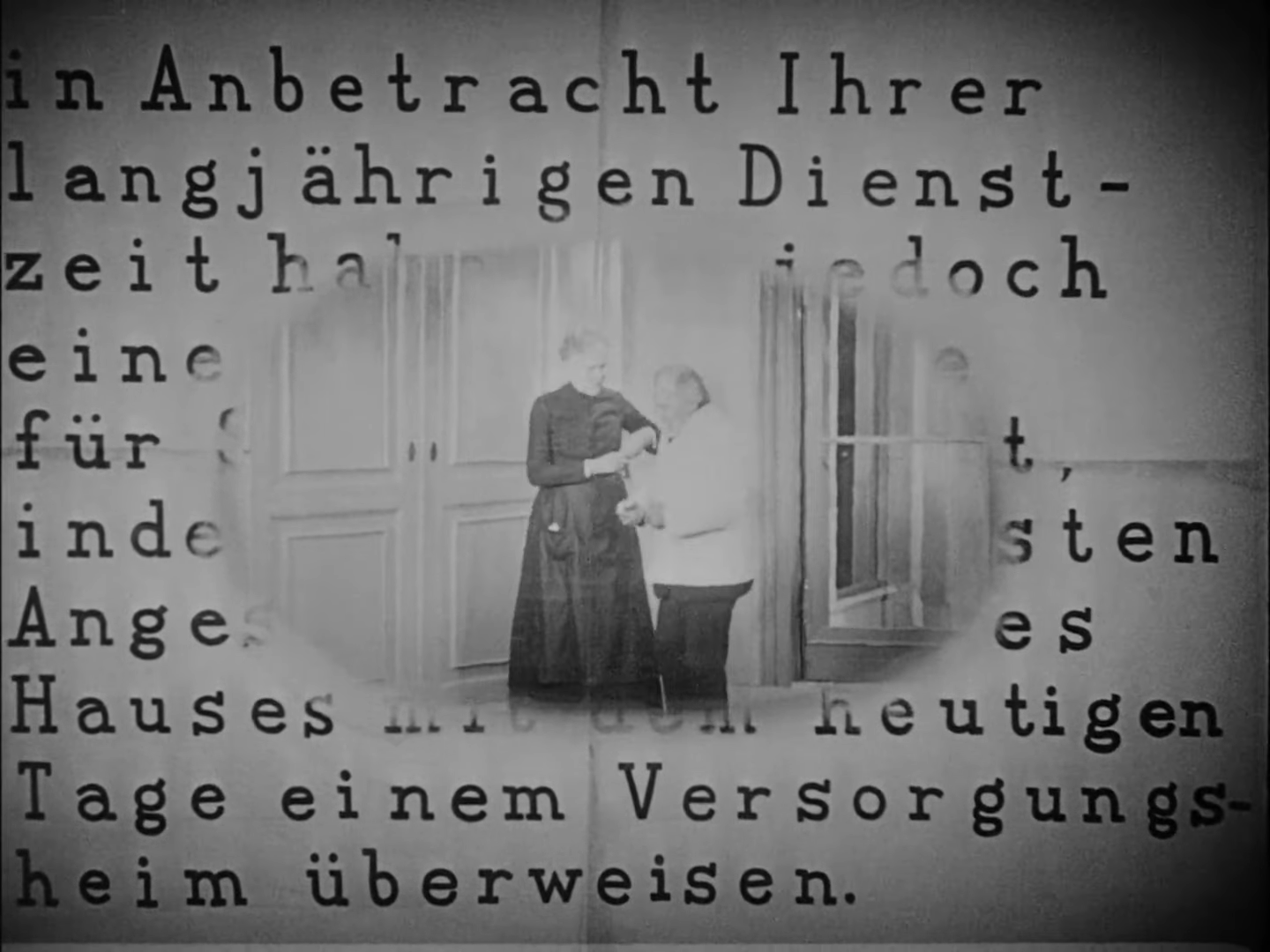

When the doorman awakes the next morning though, it seems that reality hasn’t quite caught up. Too embarrassed to come clean to his family and neighbours about his demotion, he bears the weight of a guilty conscience, and through point-of-view shots we see his perception of the world stretch and blur in disorientating patterns. He finally arrives for his first day at work, yet in Murnau’s beautifully severe wide shot, this washroom looks far closer to a prison of harsh angles and dingy lighting. The mirror which extends an entire wall simply reflects his shame back at him, and next to it he sits alone in a wooden chair, no longer dominating frames with his hefty physique but rather shrinking into the background.

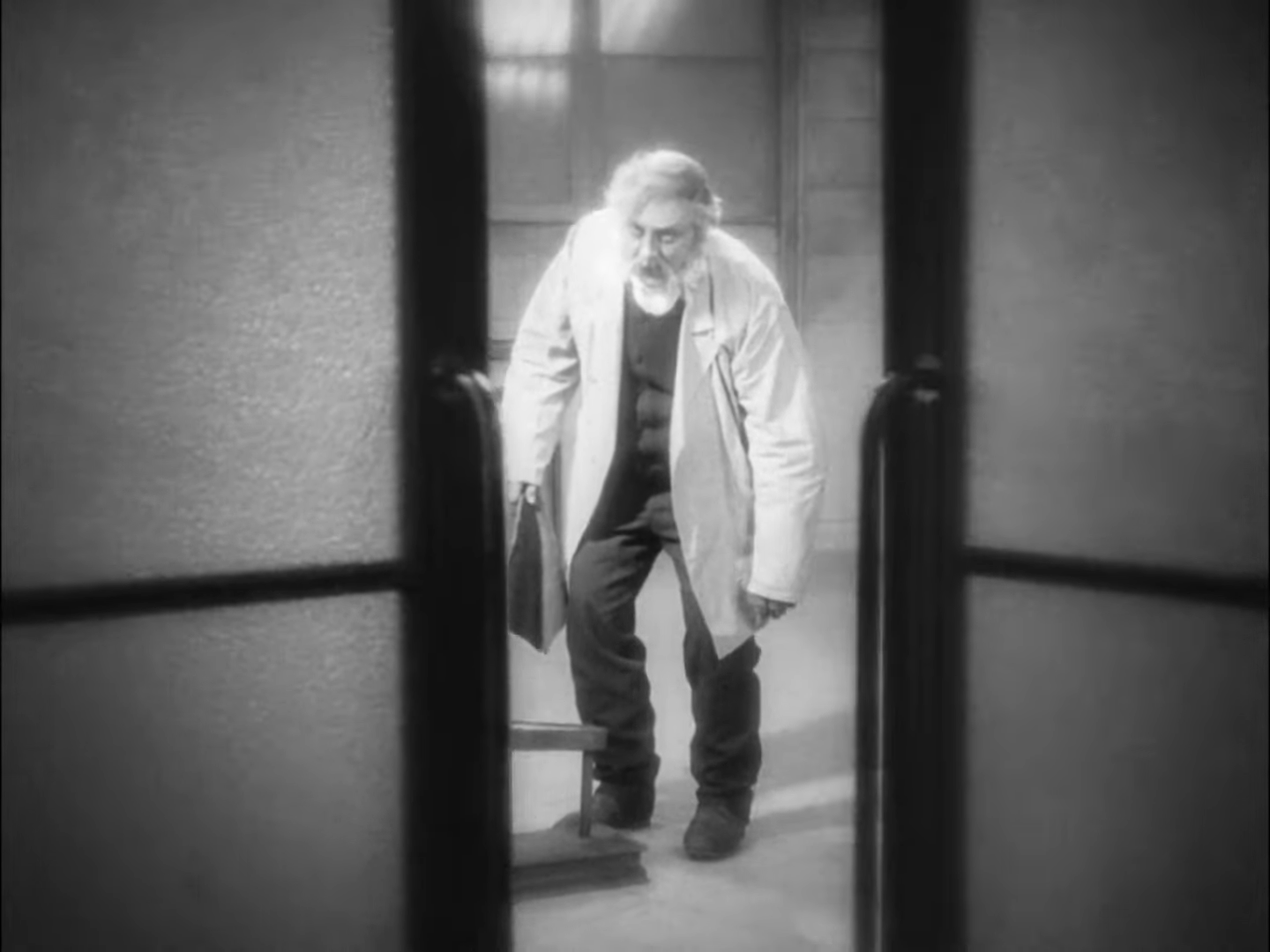

Every bit of Emil Jannings’ physical presence embodies this transformation too, making for a soaring accomplishment of silent acting that few others from this era have matched. It is a depressing thing to witness a man as large and exuberant as him shrivel up in sheepish submission, his back hunching over as he cowers before patrons and colleagues. Within Murnau’s magnificent close-ups too, his beaming smiles fall into maddened grimaces of distress and misery, and his tired eyes drift off in disoriented confusion.

There seems to be no end to the doorman’s suffering either, as it is only a matter of time before the truth of his demotion comes home to his family and neighbours. When one relative visits the hotel, Murnau plays her discovery like straight horror, suspensefully edging us towards the washroom before hurtling towards her terrified expression as he comes into view. Gossip spreads quickly around his apartment building too, and Murnau’s camera actively tracks its passage in whip pans between balconies and tracking shots into attentive ears. Catching like wildfire through the community, derisive laughter surrounds the doorman as he stumbles ashamedly through the streets, and soon inundates the entire frame as a multiple exposure effect thrusts expressions of gleeful scorn upon us.

In a pure tragedy, this is where the story would end, leaving our wretched protagonist at his lowest point. In a strange twist of fourth wall breaking justice though, Murnau’s sole intertitle confesses the pity he took on the doorman, instead bestowing upon him an improbable epilogue which lands him as the beneficiary of one Mexican multimillionaire’s fortune. Whoever’s arms he should pass away in should inherit his estate, the wealthy man’s will decrees, and it just so happens that the Atlantic Hotel’s washroom should host his fatal heart attack.

Murnau’s moving camera continues to blend elegantly with the blocking here, comically revealing the doorman’s jubilant face behind a crowd of waitstaff and an enormous cake, though formally this development is shaky at best. However pleasing it is to see him become the hotel’s most distinguished guest and give its staff the respect he never received, this jarring shift in tone has no grounding in the narrative which led up to it. Clearly Murnau’s stylistic intuitions are sharper than his plotting, so it is fortunate indeed that this fable plays out largely by way of its dynamic, enthralling visuals. It is through the avant-garde after all that we find reality slipping so elusively from our grasp, and it’s in that vulnerable state that The Last Laugh reveals the heartbreaking capacity of our self-loathing, ready to destroy us the moment we hang our pride upon the dubious, fragile illusions of social status.

The Last Laugh is in the public domain and available to watch on YouTube.