Edward Berger | 2hr

What unfolds behind the closed doors of the Sistine Chapel in the wake of a pope’s death is an esoteric mystery for the public, and a tantalising source of intrigue in Conclave. Those untouchable pillars of virtue who make up the College of Cardinals represent one of the most powerful patriarchies in the world, yet only a fool would believe they are above the messiness of material, bureaucratic machinations. Especially when the time comes for them to decide the future of the Catholic Church, factions solidify into cliques, demanding unwavering loyalty amid profuse uncertainty. The only death that takes place in Conclave is the late Pope’s, and the film’s sole action set piece is merely a footnote within the broader narrative, but the tension that Edward Berger weaves into this historic landmark is rich with all the conspiratorial speculation of an exhilarating political thriller.

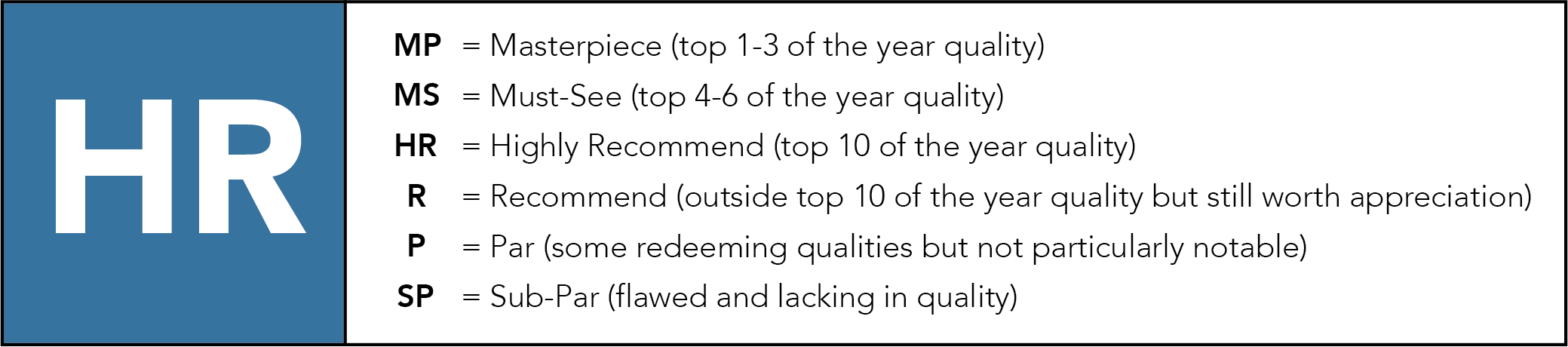

Ralph Fiennes’ performance as Dean Thomas Lawrence must also be credited for anchoring this sacred assembly in a weary apprehension, both disillusioned by the church and anxious that its leadership should fall into the wrong hands. With Berger’s camera frequently circling him and hanging on the back of his head in tracking shots, we are placed right in his uneasy state of mind, aggravated further by the deep, staccato strings restlessly driving each scene forward. It seems cruel that he should be the man to preside over the papal conclave given his personal troubles, but still he remains true to his duty. This is a process heavily entrenched in ritual and tradition, and there can be no allowance for unorthodox interferences at any point – so when the candidates themselves are caught up in self-aggrandising games of sabotage, to whom can their followers turn for spiritual guidance?

Thoughtfully adapted from Robert Harris’ novel, Conclave possesses a screenplay that is more concerned with archetypes than characters, both to its benefit and detriment. These cardinals stand for opposing sides of an internal conflict more than their specific doctrines, vaguely labelled here as reactionaries, moderates, and liberals with little regard to what these practically mean. On one hand, this broadly helps to shape the story into a microcosm of modern politics, rendering their philosophies as secondary to their trivial antagonism. On the other, it struggles to distinguish these characters beyond their shallow alliances, each equally obstinate in their goal to elect whoever best serves their own interests.

While Conclave does not engage deeply with Lawrence’s particular crisis of faith either, it at least positions his perspective as perhaps the most compelling of this religious debate. “Certainty is the great enemy of unity. Certainty is the deadly enemy of tolerance,” he preaches in his homily before the first vote, encouraging his peers to vote for someone who recognises doubt as a great virtue. After all, it is from that space between two absolutes that faith is born – not that many in his audience are ready to listen with open hearts. This is nothing more than his own personal ambition speaking, they believe, coming across as an attempt to throw his name into the ring.

On some subconscious level, perhaps there is some truth to this as well. Along with Lawrence’s spiritual turmoil, he must also grapple with his own opportunistic tendencies, driving him to step forward when he realises his friend Aldo Bellini cannot lead the church’s progressive faction to victory. As such, the universe’s timely intervention at the exact moment he casts a vote in his name almost seems to be a biblical rebuke from the heavens, humbling him before a righteous, divine God who has a plan for all things.

Lawrence is far from the only ego present forced to face his sin though. The secrets that simmer beneath the surface of the papal conclave hold the potential to topple candidacies, and as they are gradually brought to light, each one also exposes the moral weaknesses of those religious leaders who hide behind facades of reverence. Whether they concern long-buried mistakes from thirty years ago or recent acts of deep-seated corruption, the humiliation that comes with their revelation brings prideful men to heel, begging the question of who can really be trusted with such consequential responsibilities.

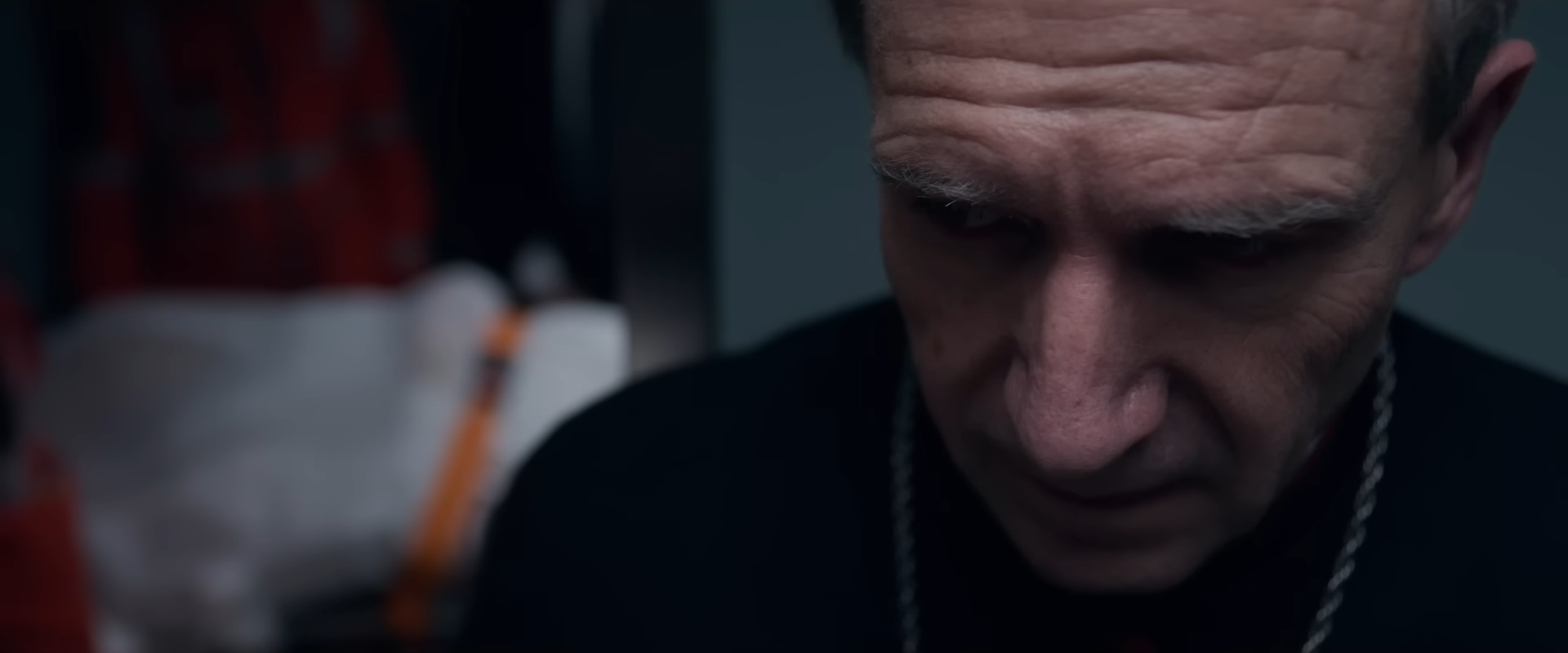

That Berger brings such solemn gravity to his staging of this confined drama only deepens the burden upon these characters’ shoulders as well, seeing him constantly underscore the sharp angles and perfect symmetry of the Vatican’s Renaissance architecture. Beautiful marble interiors, plazas, and colonnades host crowds of cardinals in their black and red attire, collectively moving in uniform patterns around the Apostolic Palace and the Domus Sanctae Marthae, and forming a particularly striking composition as they head towards their final vote beneath white umbrellas. Even as they wait around between votes, Berger turns yellow and red plaster walls into striking backdrops for their idle smoking and texting, while inside he casts the eyes of history upon them through montages of the Sistine Chapel’s vibrant frescoes.

This is evidently an environment bound by precise order, and the fact that Berger took liberties to make the cardinals’ living quarters even more prison-like than real life only further emphasises its severity. As a result, when this rigidity is compromised to even a minor extent, we can feel the full weight of its implications. This particularly comes into play when we consider the role of women in Conclave who are relegated to minor and supporting roles, much like in the church itself, yet who bear incredible influence upon the formal proceedings. Isabella Rossellini’s stern, authoritative turn as Sister Agnes stands out here even in her limited screen time, balancing her devotion to the church against her desire to see unworthy candidates held accountable, and eventually allying with Lawrence to see the Lord’s will be done.

With this consideration of gender roles in mind, the final secret revealed in Conclave makes for a particularly earth-shattering subversion of the Catholic Church’s dogmatic power structure, treading a narrow line between stringent dichotomies. If the lead-up to it were not so hinged on a contrived, idealistic plot device that overrides all the political game-playing we have witnessed, Berger might have stuck the landing even more, but the resolution nonetheless gives tangible meaning to Lawrence’s acceptance of a life without certainty. As this entire process has demonstrated, an institution that is focused on tradition more than the future is damned to fall on its own sword, blinded by a strict adherence to icons loaded with influence and stripped of moral substance. In Conclave, these icons do not necessarily need to be demolished – it is the periodic reinvention of what they stand for which grants longevity to the fundamental principles of their diverse, devoted followers.

Conclave is currently streaming on Amazon Prime Video, and is available to rent or buy on Apple TV and Amazon Video.

The Black actor Isabel Msamati is a standout in one scene in particular. He gives the 2nd best performance in the film in mostly one standout scene. The score in the opening scene is horrific. It’s all Ralph Fiennes show though. Although there is no real character arc or much of a clear motif for his character.

Agreed that Msamati was very impressive in that scene. Lawrence’s character might have been stronger with more specificity around his crisis of faith, but I still think there is just enough of an arc there in his renewed hope in the church and overcoming his own pride.

He is conflicted and a good guy. But there is not much more other than that. I find zero faults in Fiennes’ acting. But I wish the writing was better.

I was thinking a breakdown in front god praying in the church alone would have helped flesh out his character and the audience to get behind him. The whole time I was thinking he would turn out to be a serpent at the end with a vicious smile.

Also there is a clear subtle thing included in the umbrellas photo(the best shot in the film). It’s clever. The umbrella is missing from one of the popes. I think Lithgow.

I noticed that – it was hard to tell who that was or whether it was a minor oversight.

This is clearly not an oversight. This happened around the same time the Lithgow character is trying to cover his misdeeds.

Pingback: 2025 Oscar Predictions and Snubs – Scene by Green

Pingback: 2024 in Cinema – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 25 Best Male Actors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green