Michelangelo Antonioni | 2hr 6min

Television journalist David Locke doesn’t know much about fellow hotel guest Robertson, but based on their limited conversations, it appears that he is joyfully liberated from the burdensome responsibilities that so many carry in modern society. “No family, no friends. Just a few commitments,” the mysterious Englishman shares in their first meeting. “I take life as it comes.” Now as Locke finds his new friend’s body lying cold in his room, he does what any man seeking to escape an unfaithful wife and unsatisfying job would do. This is his opportunity to make a clean break from his dull, disappointing life, reporting the death as his own and adopting Robertson’s identity.

In this moment, Michelangelo Antonioni plays a familiar trick of discontinuity that he had previously experimented with in L’Eclisse and Blow-Up, though in The Passenger it is his camera movement rather than editing which shifts our perception of reality. As Locke forges a new passport, an audiotape recording of his and Robertson’s first meeting plays over the top, and we slowly pan towards the balcony where the voiceovers imperceptibly transition into a live flashback. When their discussion begins to wrap up, Antonioni similarly drifts the camera across the room back into the present day, effectively eroding the boundaries of time and identity which have long been missing in Locke’s life. Perhaps becoming an entirely different person is the key to finding that purpose he has never known, our protagonist resolves, and thus he sets out on a globetrotting journey meeting all of Robertson’s scheduled engagements.

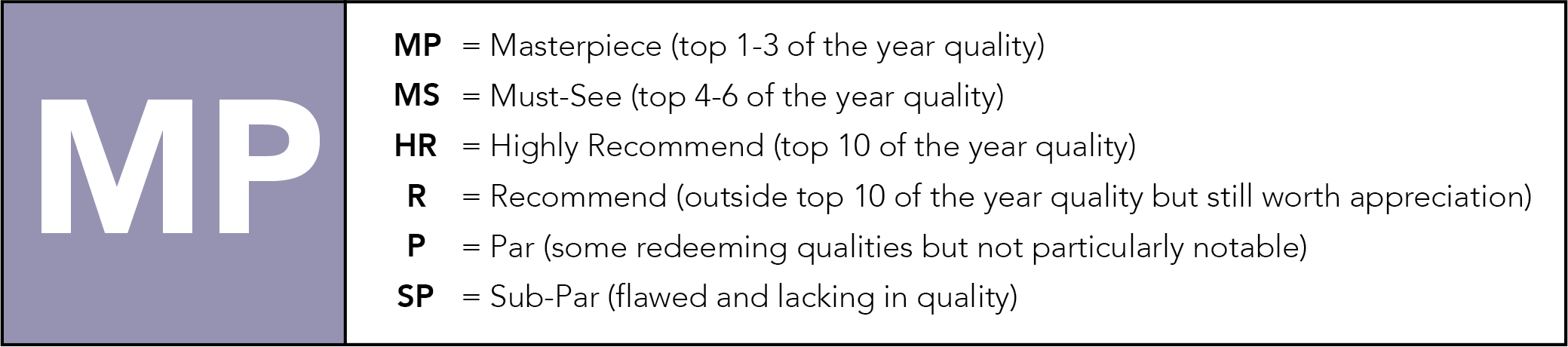

The Passenger’s scope is immense, spanning multiple countries across Europe and Africa which each hold some sort of clue to Robertson’s actual identity. This narrative might conceivably sound like a mix between Alfred Hitchcock and The Talented Mr. Ripley, though Antonioni is not so concerned with the meticulous plotting of its mystery, instead framing Locke as a man aimlessly wandering both a literal and figurative desert. This is where we meet him after all, not long before he is abandoned by his guides and gets his Land Rover stuck in a dune. He can scream at the sky all he likes, but that simply drives him to the point of exhaustion, collapsing him against the car as Antonioni’s camera despairingly pans across the Sahara’s vast, flat expanse.

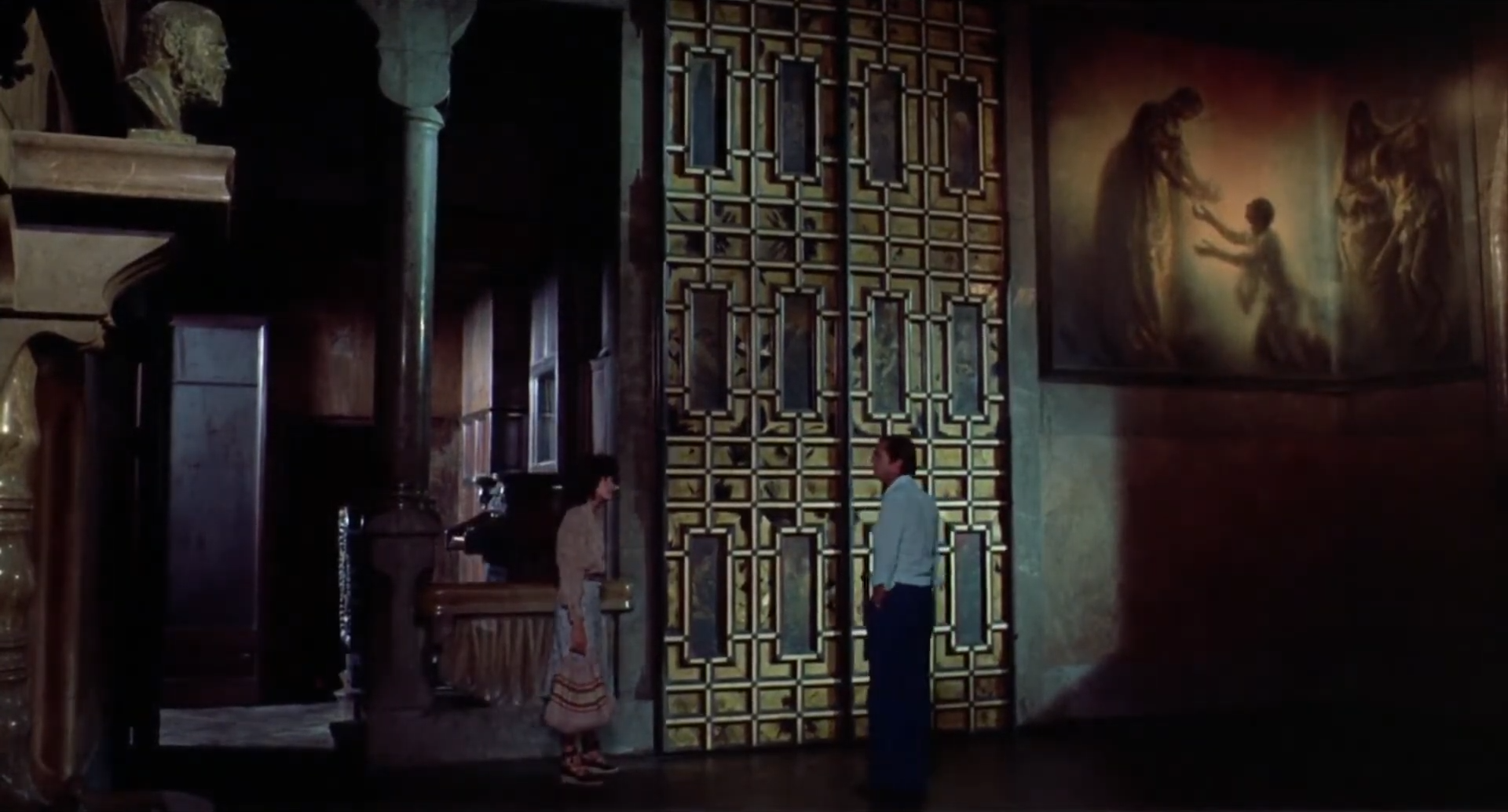

There are no manmade structures bearing down on Locke in this environment, and no busy crowds to stifle his expressions of anguish. Even when Antonioni does introduce magnificent architectural marvels into his mise-en-scène though, these aren’t the giant, oppressive monuments of his previous films, subjugating characters to a harsh, modern civilisation. Locke is not dominated by his surroundings, but lost in them, drifting through scenes set against vast backdrops of apartment buildings, cultural landmarks, and abstract public artworks. Somewhat ironically, this is also the sort of freedom that he relishes, every so often taking the time to appreciate this newfound independence. Leaning out of a cable car spanning a channel of water, he stretches his arms wide open, and he almost seems to fly as an overhead shot revels in his liberation.

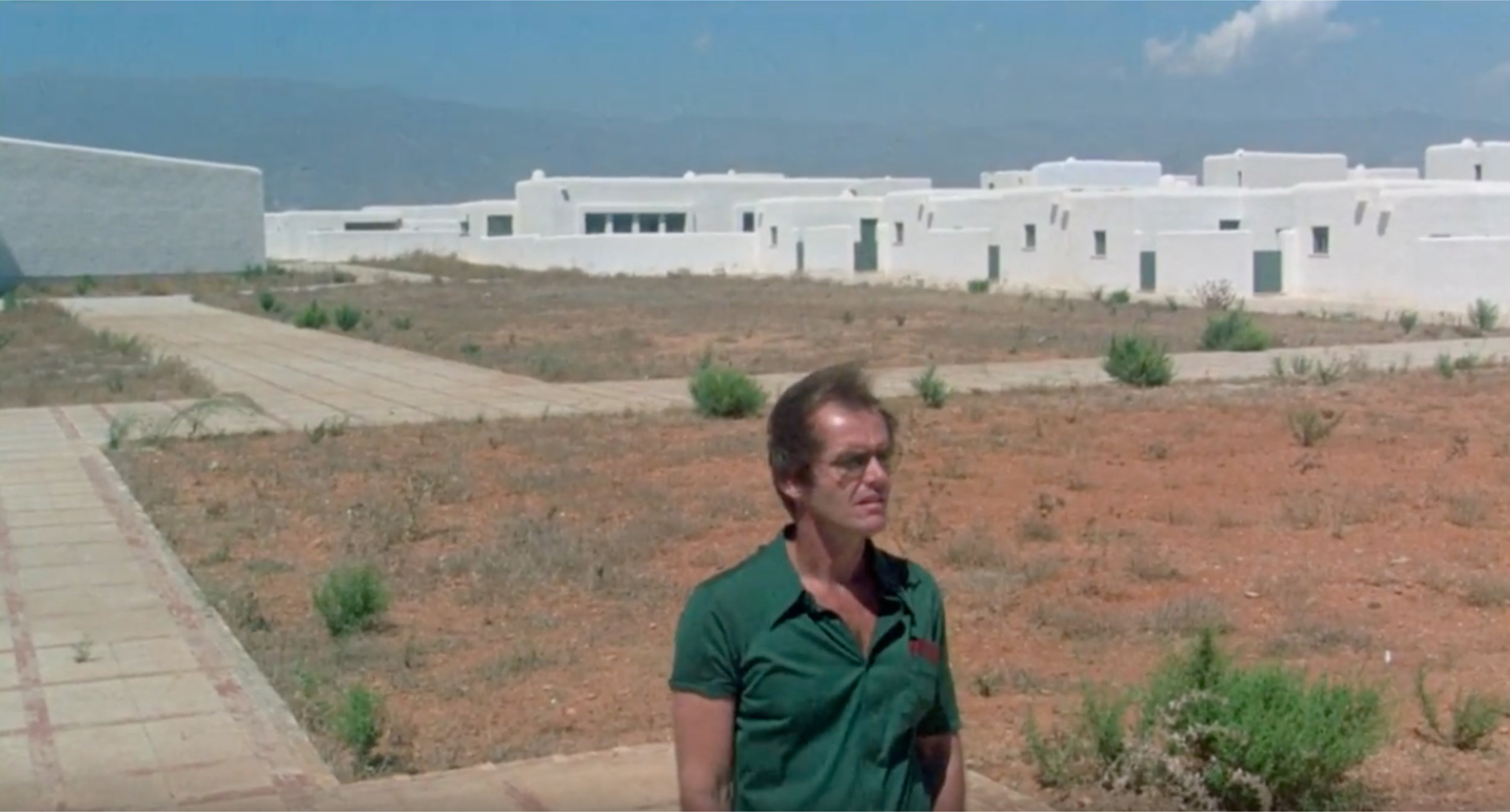

Negative space is key to Antonioni’s compositions here, underscoring the emptiness which encompasses both urban and rural locations, though he often fills them in with textures that project Locke’s mental state onto the world. His outfit almost blends in with the white-washed plaster walls and green shrubs of a rustic Spanish settlement, and when he begins to realise that his wife Rachel has sent a television producer to track him down, his fragmented psyche manifests in a mosaic sculpture decorated with jagged ceramic shards.

Without any clear boundaries defining these eclectic settings, the tension between Locke’s desire for both freedom and purpose sits at the heart of his inner conflict. To unite the two, he must effectively design his own labyrinth of winding paths and dead ends – and now that he has officially taken Robertson’s identity, what better artefact is there to arbitrarily craft it from than the dead man’s diary? Not even he knows what this itinerary might lead to, though it is surely more enticing a prospect than returning to the wife, house, and job that he has grown so disillusioned with.

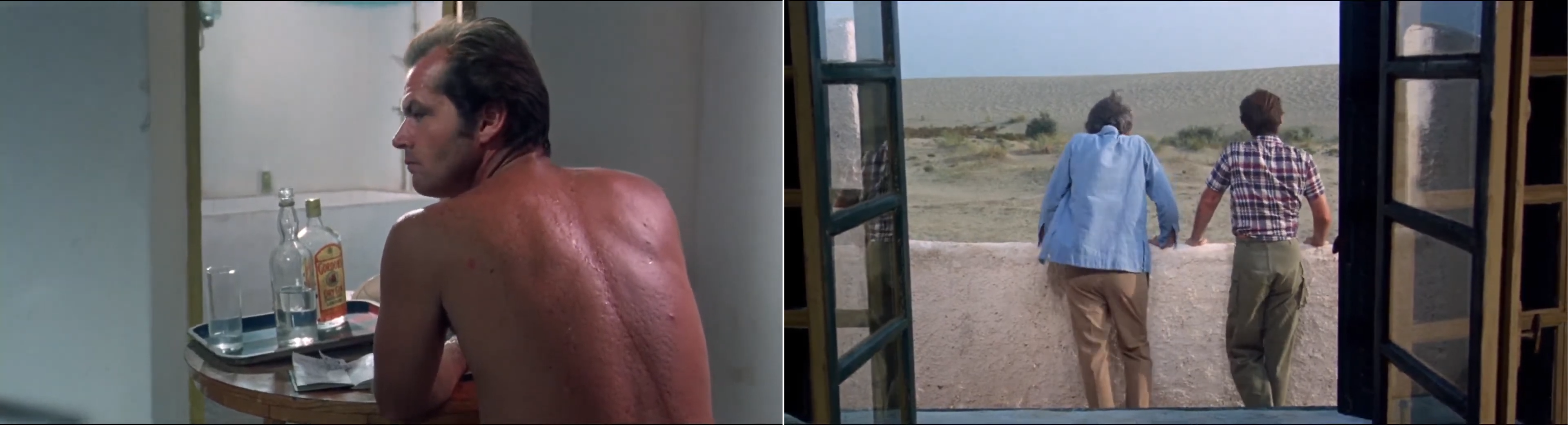

Jack Nicholson is sublime in his navigation of this quest, turning in his bombastic screen persona for a subdued uncertainty that pairs nicely with Maria Schneider’s gentle encouragement, spurring him on as a loyal companion. With no name given to her other than the Girl, her identity is kept vague enough to become whatever Locke needs in any given moment. It is fitting that he should introduce her as an architecture student as well, displaying an intellectual appreciation and understanding of their environments, even if she can’t always directly assist him. He alone must be the one to pave his path forward, discovering what it means to a live a life on his own terms.

The danger that comes with this unfettered independence is simply a part of the deal, Locke reasons, but there are certainly caveats here he would rather dismiss. When he learns of Robertson’s profession as a black-market arms dealer, he does not retreat to the comfortable confinements of his old life, but instead maintains the belief that he can keep outrunning trouble before it catches up to him. With both Rachel and a militant guerrilla movement on his tail though, each believing they are looking for Robertson, it is evident that the consequences of his decisions are inevitable – and perhaps there is a subtle recognition of this in his final monologue to the Girl as they lay down together in a rural Spanish hotel.

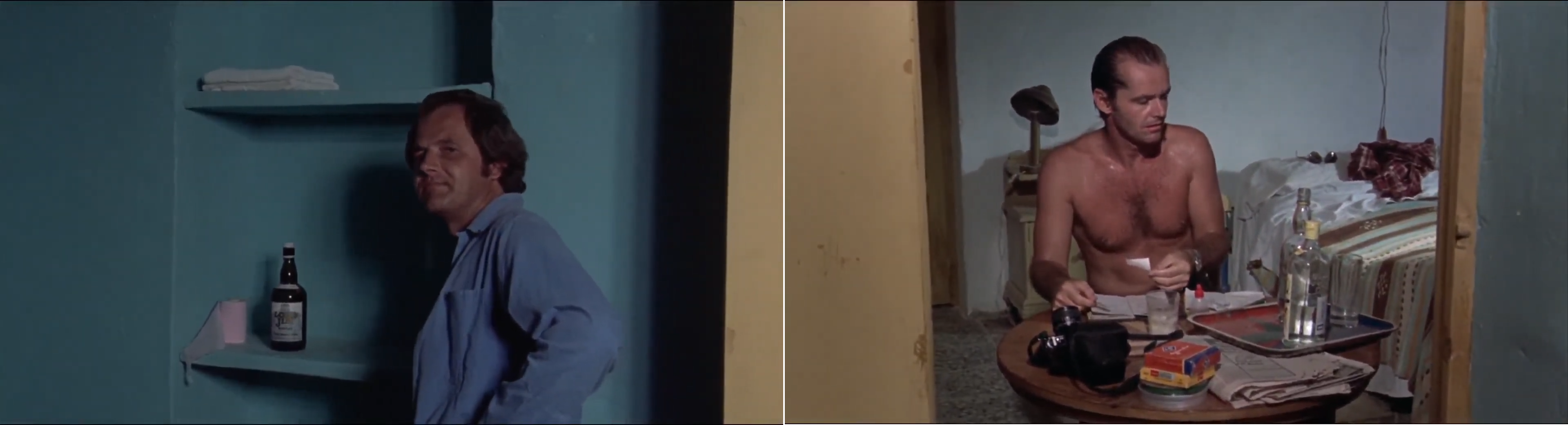

In the story Locke tells, the joy that a blind man found in regaining his sight was quickly dashed upon realising that “the world was much poorer than he imagined.” It doesn’t take a great imagination to recognise him framing himself in this allegory of existential suffering. The darkness that once consumed them both at least concealed the truth of life’s ugliness, and in the blind man’s case, suicide was tragically the only escape.

This is not the end that Locke is destined for in the final minutes of The Passenger, though his listless resignation to an early grave certainly aligns their respective deaths. The 7-minute long take which skirts around the edges of this incident formally caps off the wandering camerawork that has pervaded the film, and perhaps even stakes its claim as the strongest single shot of Antonioni’s career, divorcing us from Locke’s perspective as he lays down in his hotel room. With only his legs in frame, we peer across the bed at the window grills, opening onto the bright, dusty courtyard where each plot thread converges at once.

As the Girl lingers in hesitation over whether to leave, the African assassin who has been right behind Locke for some time arrives, and Rachel arrives in a police car a couple of minutes later. Drifting forward ever so slightly, Antonioni’s camera frames everything perfectly between the iron bars, before it squeezes through the narrow opening and emerges outside. Antonioni’s nifty manipulation of the set in this moment lifts us beyond Locke’s subjective perspective, effectively defying physics as we take on the role of an invisible, neutral observer wandering the scene, and patiently wait for Locke’s inevitable collision with his pursuers.

Like our protagonist, we are but passengers on this journey, fluidly taking the point-of-view of whatever character we are positioned to identify with. There is an entire world beyond Locke’s solipsistic journey, but only now as the camera circles back on the building to look through the window from the other side do we view him within alternative contexts that he was blind to. Little did he realise when stealing Robertson’s identity that he was also adopting his fated demise, and the aftermath as well reveals a complicated legacy in his wake. “Do you recognise him?” the police officer asks Rachel, whose response in finding her lifeless husband rather than Robertson is layered with profound disbelief.

“I never knew him.”

Given the identical position of Locke’s body from when we last saw it, we can infer that there was little struggle when the assassin entered the room. That The Passenger should conclude not with this though, but rather a far simpler shot of the Girl departing the hotel at dusk only underscores his total irrelevance in a world that keeps moving on, fading his strange, fruitless bolt for freedom into the milieu. Antonioni does not seek to overwhelm us with grief here – that would be far too straightforward in its clear distinction between life and death. Like Locke, we must confront the desolate, senseless banality of the emptiness, and continue living with it long past his consciousness is granted a merciful release.

The Passenger is not currently streaming in Australia.

Pingback: The 50 Best Male Actors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Cinematographers of All Time – Scene by Green