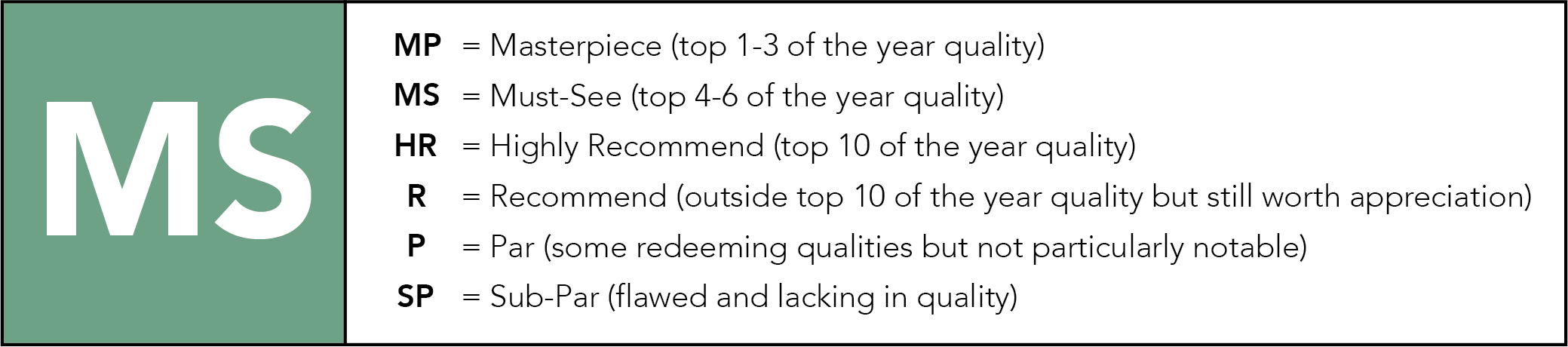

Sergei Eisenstein | 1hr 51min

The Teutonic Knights’ attempted invasion of Russia in the 13th century was not the last time the Slavs would feel the heat of rising German forces. Tensions between the Soviet Union and the Third Reich were similarly strained when Sergei Eisenstein was commissioned to direct Alexander Nevsky, seeing him use the titular Prince’s grand conquest of his foes to inspire audiences with patriotic solidarity. It had been ten years since his previous film, and the artistic failures he suffered while travelling Europe and the Americas brought him back to his home country, reluctantly asking Stalin for one last chance to prove his value. Supervised by co-director Dmitri Vasilyev and co-writer Pyotr Pavlenko, his instructions were simple: stay on schedule, do not stray into experimentalism, and do not embarrass the Soviet Union.

That Eisenstein was still able to create a film of such majestic ambition without stepping outside these restrictions is a testament to his incredible craftsmanship. Alexander Nevsky may not possess the formal innovation of his silent works, yet this venture into sound cinema maps out its historic clash of medieval armies with great finesse, inviting famed Russian composer Sergei Prokofiev to arrange a score that rumbles and sweeps across battlefields and villages. “The Russian lands we shall never surrender / Whoever rises against Russia will be smitten,” his male chorus sings in the opening scene after Nevsky refuses to join the Mongols’ Golden Horde. Although his vanquishing of Swedish invaders upon the Neva River has earned him a formidable reputation, his talents are not for sale. He is a hero for the Russian people, and a man this remarkable no doubt deserves his own folk songs to accompany his tale.

Even before we reach the monumental Battle on the Ice, the scale of this narrative is equally matched by its astounding cinematic style, often tilting the camera at low angles to gaze up in awe at marvellously blocked scenes laid before us. The horizon sits low in the frame as figures traverse barren hillsides, and it disappears entirely when Eisenstein poses them against vast, grey skies, often with the domed roofs and arches of their buildings rising up in the background. The Teutonic Knights receive similar visual treatment as they overrun the city of Pskov, though they carry a far more daunting air of sadistic, almost cultlike ruthlessness, tossing children into fires and holding crucifixes aloft. Eisenstein’s montages do not unfold with the radical flourishes of Battleship Potemkin or Strike for once, but rather carry through a deep, sombre grief in their continuity editing and axial cuts, punching in on wide shots to underscore the horrific suffering of the Russian people.

It is no coincidence that the helmets worn by these invaders bear such close resemblance to mock-ups of German Stahlhelms from World War I, nor that the bishop’s mitre is adorned with swastikas. Next to these villains, Nevsky effectively becomes a twentieth-century man facing contemporary evils, rallying Novgorod to fight for its freedom. His rousing speeches are infectious, inspiring rival warriors Vasili and Gavrilo to prove their worthiness to the maiden Olga on the battlefield, and similarly stirring the grieving Vasilisa to seek vengeance for her slain parents.

Patriotic anthems continue to ring out as the peasants of Novgorod zealously raise their weapons and torches, moving as one mass towards their common destiny at Lade Chudskoe. There, Vasili and Gavrilo are ordered to take charge of the vanguard and left flank, while Nevsky leads the right flank. If his strategy works, then this should crush the Germans’ wedge attack, and the lake’s thawing ice will shatter beneath the weight of their heavy armour.

It is one thing to hear the Prince’s genius in theory, and another to behold it in action. The Battle on the Ice dominates almost thirty minutes of the film’s runtime, and stands among Eisenstein’s greatest artistic triumphs, setting a cinematic standard for medieval conflicts that would influence many legendary directors from Orson Welles to Stanley Kubrick. As the suspense slowly ratchets up in anticipation of the first charge, Eisenstein surveys the layout, obstructing shots of the Teutonic army gathering in the distance with a forest of spears sprouting from Nevsky’s forces. Vasilisa is one of a hundred Russian troops stationed across this vast, flat expanse, but here her focused expression is foregrounded, embodying the grit and strength of a nation that refuses to surrender quietly.

Finally, the Teutonic Knights’ charge begins. From low camera angles that move with their horses, they seem to float like faceless spectres, and Prokofiev’s score builds its chants and horns to a dramatic climax before abruptly cutting out with the violent clash of both armies. Eisenstein is not content with simply capturing random chaos here, but choreographs the battle with tremendous clarity, closing in on smaller skirmishes between foes while tracking the movement of larger units. Though the Germans begin to make ground on the Russians, cutaways to Nevsky waiting for the moment to launch his surprise flank attack reassure us of his plan, and promise hope as he charges forward with a bold rallying cry – “For Rus!”

Eisenstein’s editing paces this battle perfectly, slowing the action at key points as tactics are reassessed, and then building it up again with a fresh shift in power dynamics. We see this unfold when the Germans retreat into a defensive formation and rain arrows on the Russians, but also in the sweet, smaller-scale interaction that sees Vasilisi toss a wooden spar to a surrounded Vasili, saving his life. This is the sort of selfless bravery which holds Nevsky’s forces together while the Teutonic Knights crumble, forcing them onto the frozen lake where, just as he predicted, they shatter the surface and sink into its depths. Cinematographer Eduard Tisse’s practical effects are spectacular all throughout this battle, simulating wintry landscapes with lens filters and chalk dust, but it is here that his genius truly shines in constructing ice sheets out of melted glass and collapsing them upon deflated pontoons.

Nevsky’s victory is decisive, though as the camera slowly drifts over the field of slain warriors, Eisenstein takes a moment to mourn the sacrifices that have been made. “He who fell for Russia has a died a hero’s death / I kiss your sightless eyes and caress your cold forehead,” a lone female voice laments, before turning to the glory endowed upon those returning home.

“As to the daring hero who survived the fight,

To him I shall be a loyal wife and a loving spouse.”

Indeed, Nevsky’s liberation of Pskov brings romantic resolution for his warriors, neatly tying up their own lingering arcs. With Vasili proclaiming Gavrilo the second-bravest fighter on the battlefield, he is the winner of Olga’s hand in marriage, while Vasili is more than happy to marry the bravest – his saviour, Vasilisi. The curtains are fully pulled back on the Soviet propaganda behind Eisenstein’s artistry in this moment, idyllically promising great rewards to those who put their lives on the line for Russia, as well as its alarming inverse to those who threaten war,

“He who comes to us with a sword shall die by a sword!” Nevsky warns, and it is plain to see here the threat that Stalin wishes to send to his own enemies. Eisenstein may have acted as a reluctant mouthpiece for the Soviet Union, though it is evident in Alexander Nevsky that he saw these political messages as an unfortunate mandate. Still, to forge an impassioned connection to the past through moving images, music, and the skilful synthesis of both – that alone justifies the noble pursuit of creativity in an autocratic culture that threatens its very existence.

Alexander Nevsky is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel and Tubi TV.

Pingback: Sergei Eisenstein: Symphonies of Soviet Cinema – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Edited Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Film Editors of All Time – Scene by Green