Oleksandr Dovzhenko | 1hr 15min

The symbiosis between man, machine, and nature is a delicately choreographed dance in Earth, and it isn’t long after farming peasant Vasyl introduces a tractor to his community that we witness each unite in seamless synchronicity. Wheels carve out trenches in the soil, a steady stream of wheat flows through the harvester, and workers efficiently prepare it for the threshers, where unhusked grains shake in rhythmic motion along conveyer belts. After being crushed into flour, bakers swiftly mix and knead it into dough for the ovens, where bread is produced for the hungry masses.

This methodical assembly line sequence may be the closest Earth gets to non-fiction, though Oleksandr Dovzhenko also more broadly dedicates his film to depictions of collectivist agriculture, much like Sergei Eisenstein did a year earlier in his documentary The General Line. Under this system, plots of land owned by wealthier peasants known as kulaks would be consolidated into state-controlled enterprises, with the intention of freeing exploited labourers and industrialising the Soviet economy. Beyond presenting mere fact or opinion of the matter though, Dovzhenko also uses it as the basis of his invigorating visual poetry in Earth, meditating on the profound relationship that binds humans to the land that feeds them.

Compared to Sergei Eisenstein’s montage theory which sought to collide images in harsh juxtaposition, Dovzhenko’s editing is far more lyrical, emphasising the unity of all life on this planet. Clearly some of cinema’s most spiritual directors have drawn from this too, whether it is Terrence Malick finding divine inspiration in its graceful shots of workers in wheat fields for Days of Heaven, or Andrei Tarkovsky recreating the ethereal gust of wind rippling through long grass in Mirror. The death of Vasyl’s grandfather which occurs in Earth’s opening scene is not a disruption of such organic cycles, but rather a peaceful transition from one state of existence to another, seeing him lay down by an apple orchard surrounded by family. At the moment of his passing, Dovzhenko poignantly cuts to a sunflower gently swaying in the breeze, and thus reveals the fruits of this farmer’s labour thriving beyond his expiry.

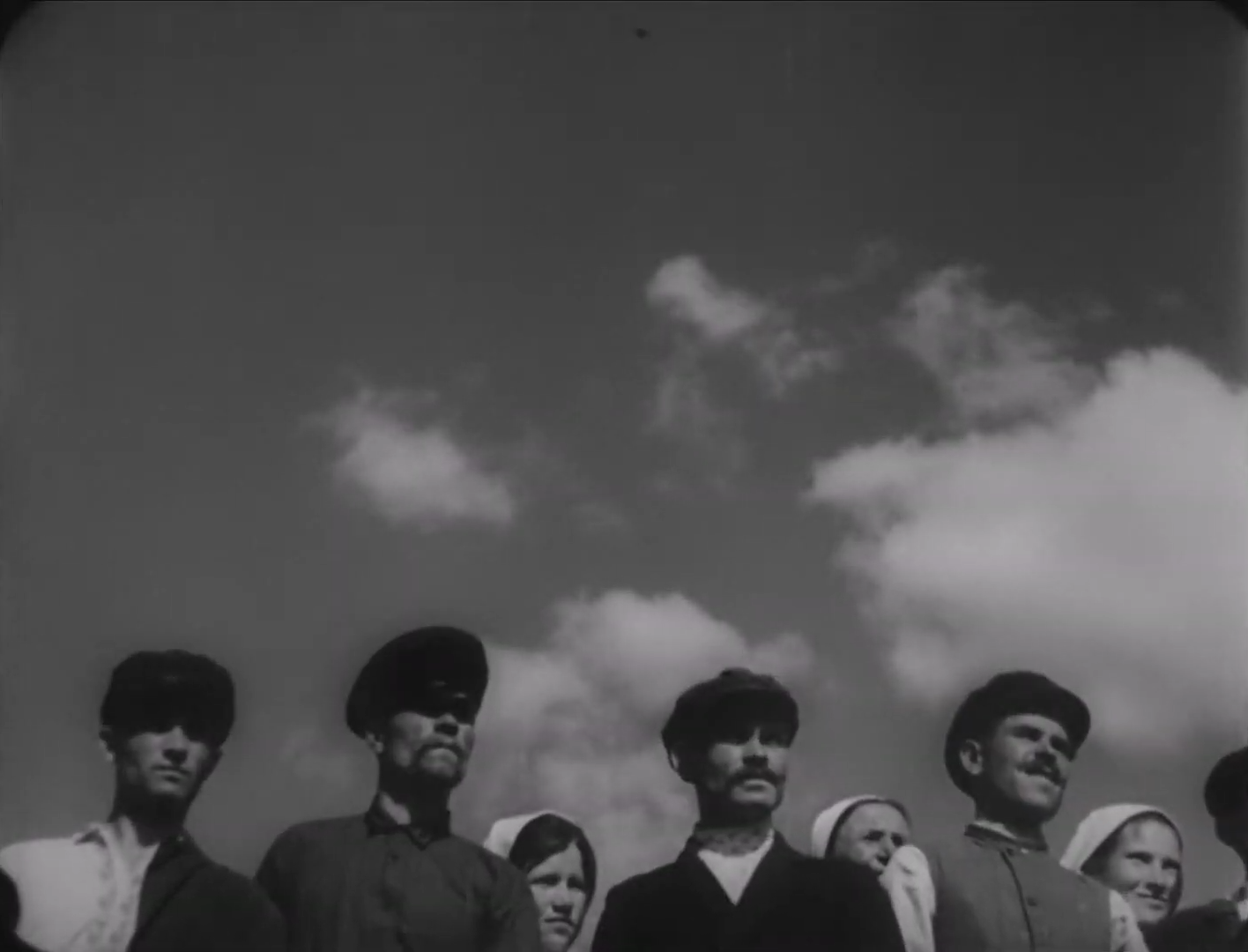

One would almost assume that Earth is a soothing expression of pantheistic spirituality were it not for the Soviet Union’s policy of state atheism in this era, though Dovzhenko’s open admiration of the Ukraine’s rural landscapes manages to skirt religious controversy, even as he turns his camera to the heavens. The low angles of vast skies become a strong visual motif here, pushing the horizon to the bottom edge of the frame in long shots, and forming cloudy backdrops to humans, animals, and plant life standing in tranquil stillness. These rural farms are as close to paradise as one can find on earth, yet political divisions in the community nevertheless threaten to strangle their natural evolution alongside Ukraine’s burgeoning agriculture industry.

As we see in the economic conservatism of Vasyl’s father, Opanas, the kulaks are evidently not the only ones resistant to the collectivism that has swept through the village. He has manually worked the land his entire life, and the state’s rapid shift towards newer technologies is unnerving, driving a wedge between him and Vasyl who excitedly leads the movement’s charge into the future. Their initial confrontation plays out in mid-shots of their backs turned to each other, but as tensions rise, Dovzhenko turns them around and gradually cuts in tighter to their incensed expressions. Quite unusually though, Earth does not depict the black-and-white morality of other Soviet propaganda films of the era, instead allowing for more nuance in its characterisations. Opanas is not the villain of this piece – quite the opposite in fact, as his son’s eventual murder at the hands of an embittered kulak suddenly positions him as our unlikely protagonist.

Vasyl died for the new life, and so he is to be buried according to the new ways, a bereaved Opanas declares. There are to be no priests or prayers at his funeral, and in their place the community will sing songs of hope for the future. As Vasyl’s body is carried down the street in a procession, tree branches reach out to caress his face, and in one delicately framed shot he even seems to drift by on a sea of flowers. People and nature alike mourn his passing which, unlike his grandfather’s, has momentarily disrupted the circle of life.

It is during this sequence as well that Dovzhenko’s editing begins to broaden its narrative scope, building to a climax in its deft intercutting between multiple side characters. As the spurned Russian Orthodox priest prays for God to punish the sinners who have refused a traditional service, Vasyl’s bereaved fiancée Natalya cries out in agony, and his killer’s public confession falls on the deaf ears of the grieving, radicalised crowd. Suspicions of his culpability weren’t exactly secret, but now as the guilt-ridden kulak rolls in the dirt madly proclaiming “It’s my earth! I won’t give it up!”, it is apparent that the collectivist movement has already delivered his moral punishment.

Perhaps most moving of all though is Opanas’ face among the masses, not broken by anguish, but listening to his son’s eulogy with stoic resolve. “You, Uncle Opanas, mustn’t grieve!” the speaker pronounces. “Vasyl’s fame will fly around the entire world like our Bolshevist airplane above!” Even the skies begin to weep at this point, showering the orchards below with nourishing rain, before concluding with Natalya rediscovering love and security in the arms of another man. The transfer of power back to the Ukrainian people is not bloodless in Earth, but as fresh beginnings wash away old sorrows, Dovzhenko’s formal cadences realign society’s march into the future with the harmonious, seasonal rhythms of the natural world.

Earth is not currently streaming in Australia.

Pingback: Sergei Eisenstein: Symphonies of Soviet Cinema – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Edited Films of All Time – Scene by Green