Stanley Kubrick | 2hr 39min

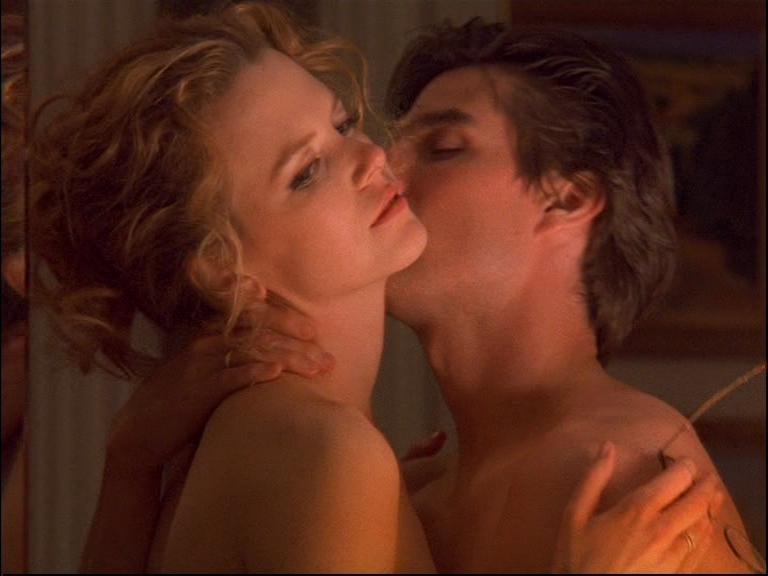

The mysterious, erotic cult that Dr. Bill Hartford infiltrates one night after a bitter argument with his wife Alice may be deeply sensual, but it can’t exactly be described as intimate. Anonymity is highly valued here, concealing the faces of its members with impassive masks even as they bare their naked bodies. Orgies are performed with ritualistic solemnity upon fine furniture, while other guests quietly watch from the sidelines of this manor’s lavish, Baroque interiors. Within the main hall too, their red-cloaked leader conducts a ceremonial prayer, chanting a deep, guttural hymn and swinging a thurible around his circle of prostrating followers. Whatever this is, Bill certainly finds it more exciting than his monogamous marriage to Alice, though playing in the realm of dreams is a dangerous game when reality inevitably beckons from the other side.

Having long been fascinated by cinema’s potential to unlock humanity’s repressed desires, Stanley Kubrick’s interrogation of matrimony and temptation finally sees him aim his camera towards the act of sex itself. It may be one of the most common human activities alongside eating and sleeping, but it is perhaps the only one to also be considered taboo, never to be spoken about in polite company. In essence, it is a secret club that we know everyone is part of, yet which also demands us to remain silent on the personal matter of our fantasies, habits, and history. As we witness when Bill is caught out and forced to remove his mask, the threat of being exposed does not simply incite shame and humiliation. It is an existential threat to our very being.

Fortunately, there is a woman at this party who is oddly protective of Bill, offering to take his punishment when he is put on trial in front of the entire cult. He is “redeemed,” and therefore allowed to leave with nothing but a stern warning to disregard what he has witnessed – though the urge to probe deeper into this underworld isn’t so easily ignored. How can he return to his ordinary life and marriage after glimpsing such a thrilling, earth-shattering secret?

Of course, this is not the only function Bill attends in Eyes Wide Shut. Being one of cinema’s greatest formalists, Kubrick foreshadows the cult’s covert gathering with a Christmas party in the film’s first act. Besides the wealthy host Victor Ziegler and old friend Nick Nightingale providing entertainment on keys, Bill and Alice do not know any other guests – an awkward situation that returns at the cult’s mansion where Ziegler and Nick are again the only acquaintances present in a crowd of strangers. If the masquerade is where identities are concealed and desires are freely expressed, then this soirée sees its guests put on courteous facades for the sake of social convention, while infidelity quietly simmers in flirtatious passes. That is, until Ziegler urgently summons Bill upstairs to save his mistress Mandy from an overdose, suddenly shining a harsh light on his private affairs.

It is clearly a thin layer of decorum separating these characters’ private and public personas, even behind the closed doors of their most intimate relationships. That is where Bill’s psychosexual journey starts in Eyes Wide Shut after all, as the day after Ziegler’s party, he and Alice jealously confront each other about the strangers they flirted with. The only reason men would ever speak to women like her is to sleep with them, he asserts, while the opposite sex is simply programmed differently. This is the belief which his faith in their marriage rests upon, and so when she confesses to a fantasy that she had about another man, his fragile world is shaken.

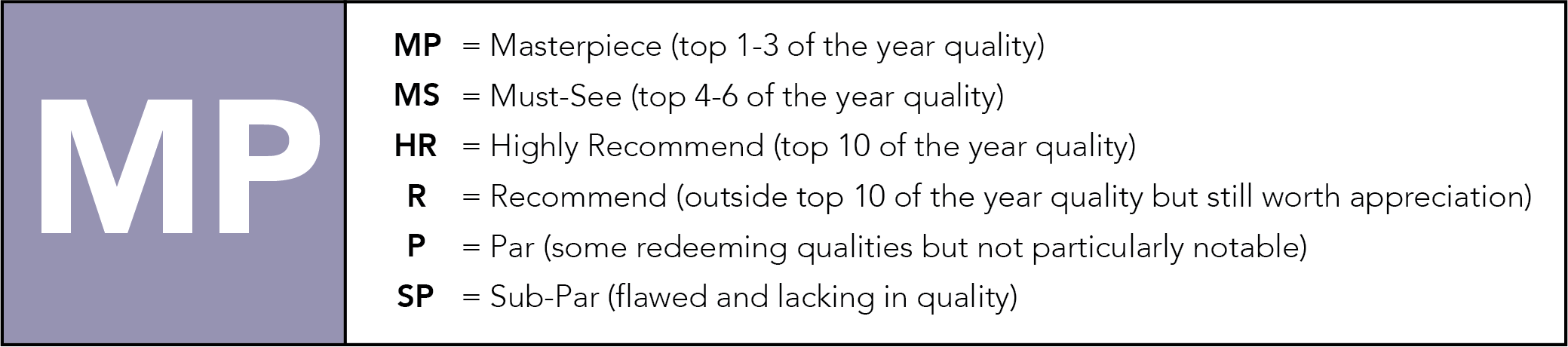

The verbal sparring between Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman here displays incredibly fierce performances from both actors, drawing from the well of natural chemistry they shared in their real-life marriage before its breakup. While the rest of Alice’s story in Eyes Wide Shut is largely confined to their apartment, jittery, monochrome hallucinations of her making love to other men continue to haunt Bill on his night-time wanderings, as he smoothly glides across rear-projected backdrops of New York’s streets.

Kubrick’s reappropriation of what used to be a classical Hollywood technique is carried through with avant-garde flair here, effectively lifting Cruise out his immediate environment and submerging him in a dreamlike state. The ambient, practical lighting that is carried through the film as a whole also serves to shape his ethereal world with vibrant beauty, constantly underscoring the holiday setting with sparkling Christmas trees, golden fairy lights, and decorated shop windows. When Bill ventures into a dim, moody jazz club, its array of coloured bulbs become bleary stars in the background of shots, while cool, blue washes in his apartment contrast its festive warmth with melancholic innocence.

Eyes Wide Shut does not evoke this cultural imagery merely for its striking aesthetic though. Like the cult’s devout worship of sex, Christmas represents the intersection of the sacred and profane. It is historically a Christian celebration, yet its pagan roots stretch even further back, while in modern-day society its spiritual significance has been entirely stripped away. Religious iconography is scarce to be found here, as Kubrick instead recognises it as an annual orgy of consumerism, encouraging us to gorge ourselves on the world’s temptations. As the final scene in the toy shop demonstrates, these may merely manifest as whimsical, material goods for children, though adults are far more likely to pursue more carnal exploits as an escape from loneliness that this time of year often brings.

For us too, the atmosphere that Kubrick builds is deeply intoxicating, lulling us into a trance strung together by impressionistic long dissolves and a minimalist piano motif alternating between two eerie notes. His camera is fully engaged with the movement of bodies, twirling around Alice’s amorous dance with an older Hungarian man at Ziegler’s party, and later slowing down into a steady, prying zoom as she and Bill embrace in the mirror. Moments like these often break up the cold sterility that is present in Kubrick’s detached wide shots, and thus we often find ourselves alternating between perspectives of the human body as either vessels of profound emotion, or merely an anatomical collection of organs acting on animal instinct.

There is no need to settle on one interpretation over the other here – Kubrick recognises that it is merely a matter of subjective versus objective perceptions, and it is frequently impossible to tell the difference. Whether he is being seduced by his patients’ daughters or going home with a prostitute, Bill is teased with sexual advances everywhere he goes, though each time he is incidentally pulled away by some other engagement. If this is a dream, then perhaps it is his subconscious mind waking him back up, pushing him back to his duties as a faithful husband and respectable doctor who must maintain a clinical relationship with the human body. He walks a very narrow line, but the fact that he never entirely throws himself into temptation even saves his life on at least one occasion, as we learn when the prostitute’s HIV diagnosis comes to light.

More ambiguously, the treatment that Bill administered to Mandy may have also incidentally been the reason he was allowed to leave the cult’s manor unharmed, as he eventually deduces the identity of his masked saviour and receives confirmation from a man who was present – Ziegler. With that said, his secret club did not actually play any role in killing her, the cultist claims. It was all a ruse to scare Bill off, and the fatal overdose being reported in the news is merely incidental.

Whether or not Ziegler is telling the truth, it is enough motivation for Bill to abandon his investigation completely. Whatever personal issues may be present in his marriage to Alice, the risk of divorce, an STD, or even death is simply too significant to be treated with such recklessness. At the same time though, can we truly appreciate what we have in front of us if we don’t grapple with the darkness that lies on the other side?

“Maybe I think we should be grateful,” Alice ponders in the final minutes of Eyes Wide Shut. “Grateful that we’ve managed to survive through all of our adventures, whether they were real or only a dream.” After all, dreams do not belong to distant, far-flung worlds. They are closely intertwined with the actions and decisions we make every day, guiding us towards tangible futures born from primal fantasies. By carefully traversing that indistinct realm which dissipates each morning upon being touched by sunlight, Kubrick delicately reveals those depraved, shadowy figures that live inside us all, and the invisible power they hold over our minds, civilisations, and humanity.

Eyes Wide Shut is currently available to rent or buy on Apple TV and YouTube.

Fucking finally ! Towering masterpiece and an absolute favorite.

I think it was Kubrick’s stepbrother that said he considered it his greatest contribution to the art form yet at the time.

What did you think of Joker: Folie a Deux?

Haven’t been able to catch it yet. Do you have any thoughts on it?

Pingback: The 50 Best Female Actors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Screenwriters of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Directors of All Time – Scene by Green