John Ford | 2hr 9min

The first time John Ford turned his camera to the pastoral villages of turn-of-the-century United Kingdom, he beat out Citizen Kane at the Oscars, delicately ruminating on a childhood spent among the mining communities of the South Wales Valleys. Contrary to its title, How Green Was My Valley excelled for its monochrome mise-en-scéne, painting hillsides black and chugging smoke from towering brick chimneys – yet to recapture this aesthetic on The Quiet Man would simply not fit the grand vision he had in mind. Thanks to his collaboration with cinematographer Winton C. Hoch, the craggy mountains, verdant pastures, and mossy stone walls of rural Ireland burst with Technicolor effervescence, setting up breathtaking backdrops for the nostalgic return of one American immigrant to his old family farm.

Retired boxer Sean Thornton is not looking to stir trouble when his train pulls up in Inisfree, though scandal is inevitable when he purchases the property that bullish local Will Danaher has been eyeing off. That he should almost immediately fall in love with Will’s sister, Mary-Kate, only further complicates this rivalry, stoking the flames of a potential brawl that Sean flat out refuses to entertain. He is a man of honour and peace, though given his violent past, it is evident that he has not always been this way. Only after witnessing the devastating power of his own brute strength in the boxing ring did he give up that life completely, and it will take more than a few verbal jabs to lure him back into a fight.

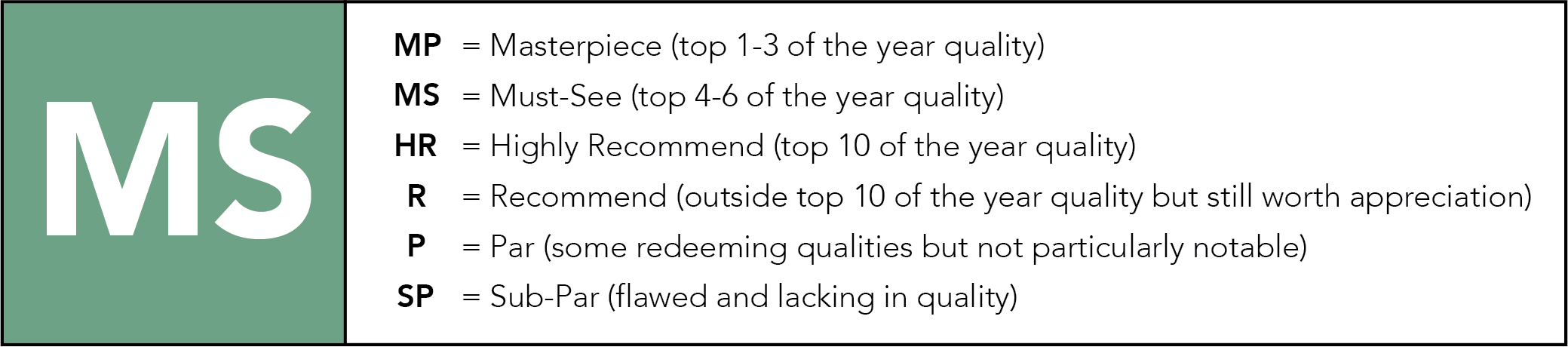

This brief venture beyond the realm of Western and war films is a refreshing change of pace for John Wayne, even if he is still typifying the masculine hero archetype with a hidden streak of fury. In place of dusty vests and cowboy hats, he wears tidy suits and berets, visually blending in with the local Irish population while his accent marks him as a foreigner. In fact, the only actor here who does cast an immediately striking figure is Maureen O’Hara, whose red and blue dress vividly stands out against Inisfree’s lush green fields and vegetation. Clearly Ford adores her sensitive command as the emotional centre of the film, dynamically billowing her red hair and dress in a powerful gust of wind when she and Sean share their first kiss, and framing her teary face behind a rain-glazed window after Will refuses to let them marry.

The constant humiliation of Mary-Kate’s brother at the hands of the stronger, kinder Sean is mostly deserved in The Quiet Man, yet the collective conspiracy that tricks him into allowing their marriage exposes a cruel underside to this tight-knit town. Will’s feelings for the Widow Tillane are his greatest weakness, and so a false rumour that she would be willing to marry him once Mary-Kate is no longer under his roof is all it takes for him to happily hand his sister off. Of course, it is only a matter of time before he realises that he has been fooled, seeing him immediately dampen the merry atmosphere of their wedding. Will’s sudden withdrawal of his dowry payment comes as a slap in the face to Mary-Kate, who considers this money her entire worth. On the other hand, Sean sees no significance in this tradition – they are officially married after all, and it does not make him love her any less.

Ford has always excelled at using his ensemble to create rich, distinctive communities, building entire societies upon the rituals, lifestyles, and comic eccentricities of the local populace, and this dynamic serves an especially crucial purpose in developing The Quiet Man’s cultural conflict. Will’s insult drives a sharp wedge between the newly wedded couple, revealing a clash of Irish and American values that turns Sean into even more of an outsider than ever. As a man of the New World, he fails to grasp the enormous weight which Mary-Kate and the entire village place on the dowry he is owed. As long as it remains unpaid, they cannot even consummate their marriage. In refusing to fight for it as well, he is essentially condemning his wife to suffer the ultimate dishonour.

The gossip which is sparked by quaint customs such as this are more of a side effect than anything else. At their core, these traditions foster a sense of camaraderie and security among neighbours, uniting them at the pub, church, and beach where jockeys race horses in friendly competition. By arranging his crowds through beautifully styled sets of 1910s pastoral décor and across magnificently weathered landscapes, Ford’s blocking underscores the importance of this fellowship as well, binding individuals together within shared expressions of joy and sorrow. Similarly crucial here is Ward Bond’s light-hearted narration as the friendly local priest, warmly reflecting on our protagonists’ romance with humour and grace, and effectively becoming the voice of the entire town.

This is evidently a culture of idyllic joy and simple tastes, given lush musical form in Victor Young’s Gone with the Wind-inspired soundtrack that soars and swings with playful Celtic inflections across strings, harps, and flutes. After locals sing a drunken rendition of ‘The Wild Colonial Boy’ at the pub, even that too exuberantly weaves its way into the score, developing a high-spirited motif that bounces with Irish pride. Were it not for Will’s stubborn resistance, Inisfree may very well be a paradise for a man like Sean looking to return to his roots, and yet if he truly wants to make a home here then he must first overcome his American ego and inhibitions.

Mary-Kate’s failed attempt to leave town is all the motivation that Sean needs to settle the score once and for all. Meeting her at the station, he grabs her by the arm and marches with stoic purpose to find Will. The excitement is palpable as crowds eagerly join his trek across town, anticipating a furious stand-off which Ford finally delivers with low camera angles and majestic blocking at Will’s farm. With Sean threatening to return Mary-Kate out of pure frustration, Will eventually concedes and pays the dowry – though certainly no one expects Sean to aggravate tensions even more by spitefully throwing the money into a furnace.

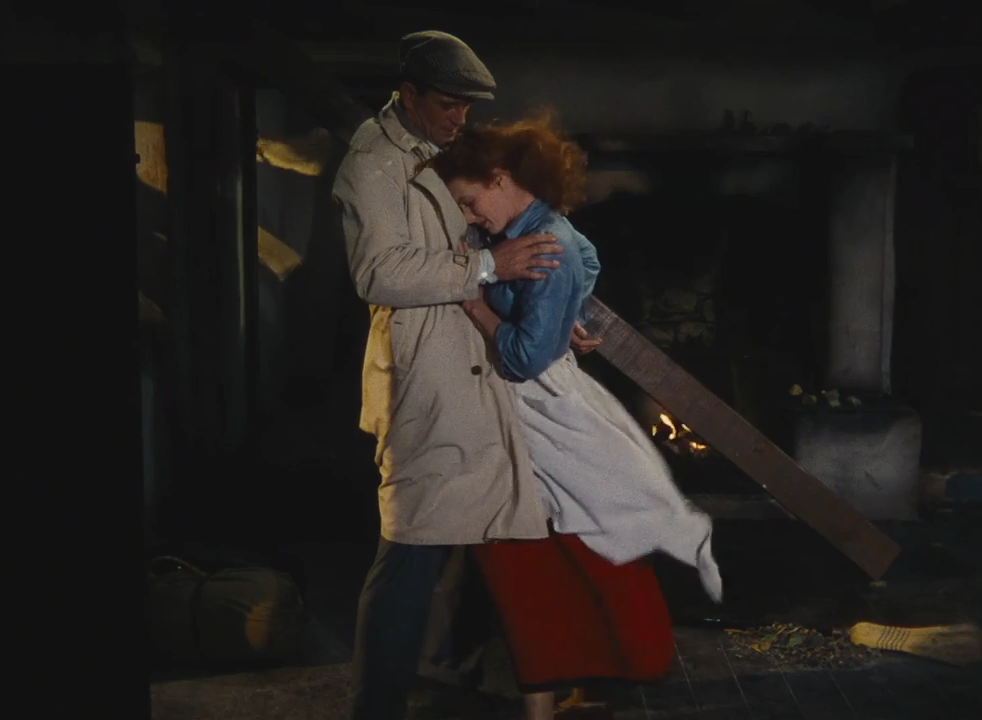

It is not this verbal exchange, but the ensuing fistfight between brother-in-laws which offers the release we have been itching for, and that much at least we have in common with the impatient townsfolk who seek drama within their mundane lives. Sean and Will’s brawl rolls across the countryside, claiming a stage as enormous as the frustration that has been quietly mounting for months, and which now explodes with cathartic vigour to snowballing crowds. Ailing men rise from their beds to join the fray, the Widow Tillane admires Will with newfound romantic interest, and even Father Peter Lonergan gets in on the action after his fellow priest beseeches him to end the madness. “We should lad, yes, we should. It’s our duty. Yes, it’s our duty…” he mutters, though his roiling excitement is betrayed by his broad grin.

Only when both combatants take a break at the local pub mid-fight do they get a chance to properly talk, confessing a reluctant respect for each other – but only for a brief moment before a quarrel over who is paying for the drinks ends with another smack to the face. It barely matters who wins and loses this match of brawn and stamina. Through the act of good-natured violence, all grudges are aired, and old disputes are officially put to rest. Unlike the culture of cutthroat American competition that Sean has come from, ill will simply cannot exist as a permanent fixture between neighbours in Inasfree. Simple problems require simple solutions, and simple love deserves a simple life. Now as Sean finally returns to his idyllic country cottage with his beautiful, red-haired wife, even his greatest rival can accept that he has thoroughly earned both.

The Quiet Man is currently streaming on Plex, and is available to rent or buy on Apple TV, YouTube, and Amazon Video.

Have you ever considered a post on The Searchers? You seem to admire it now (#11) but from your letterboxd page, you didn’t always. As for me, while I acknowledge it’s visual beauty, I find Lawrence of Arabia at least as beautiful and more impressive cinematically in most regards (the army of extras, the match/desert cut, the narrative, the rescue from the desert). The Searchers is probably the classic film I’ve struggled the most with.

I haven’t got any plans in the near future but I would like to write reviews for all my top films at some point. My struggle with it was big and I can still see its flaws, but the high points far outnumber and outweigh the low.

This is a great video which hits on a lot of the main reasons I admire it: https://youtu.be/MXnE-bA0BlU?si=ydFHQqHPqrWddJ-t

Ha ha! I love that channel, it’s my favorite on film. I wouldn’t deny that The Searchers is a masterpiece, but I wouldn’t rank it any higher than say Lawrence of Arabia. I’d even struggle to explain why it’s better than TGTBTU. (Blocking, writing – about equal, and is the bookends of The Searchers convincingly greater than the shootout in the cemetery?)

Struggle with The Searchers how ? Is it the stagey artificial sets in-between exterior scenes or the cringy comedic moments ?

Nah – the stagey sets are still beautiful, and the comedic moments might not be The Rules of the Game, but I think people exaggerate how bad they are. It’s more that even the artistic highs don’t seem necessarily more impressive to me than Lawrence of Arabia or even TGTBTU.

I reckon putting a compilation of the best shots of The Searchers against those of TGTBTU would have the former coming out ahead comfortably, but there is something to be said about how old TGTBTU makes the Searchers look with only a 10 year gap because of all the camera movement, editing and variety of angles and shots used. Not unlike going from something like Nosferatu and other silents in full and medium shots to The Passion of Joan of Arc in a different time period. 60s cinema hits different.

But I do think The Searchers peaks high enough for sure personally – “let’s go home” and the bookends is as good as it gets- just not consistently enough for a top 10 consideration. I might prefer TGBTU, it’s hard to say.

Oh yes, The Searchers is the more beautiful movie – but TGTBTU has its own peaks of cinematic style. Camera movement like you said, and also the incredible cemetery shootout, which certainly ranks among the greatest scenes in movie history. The Searchers is probably more impressive overall, but not overwhelmingly enough that TGTBTU sits at #50-100 where The Searchers is about #10 (or #1).

Maybe. I’d probably put it in that secondary great tier with Seven Samurai and Touch of Evil rather than in contention for top spot. Seems like a popular opinion in this community, I’m a bit surprised.

I agree – but we seem against the consensus, so I was curious about other opinions. Out of curiosity, what is your #1 (or top few) film(s)?

@K & @Vananila – love seeing this discussion. I think I’m also closer to you two on The Searchers, after four viewings it is more of a top 40 film for me than a top 5 film.

@K As in personal top or “Greatest Films of All Time™ very official and super objective list” ?

I guess both – it’s always your own judgement anyway, so saying its subjective is redundant. What do you consider the contenders for the best film of all time?

True, but there’s “I don’t think Raging Bull is better directed than Tokyo Story (if they’re even comparable)” subjective and then there’s “I don’t care for boxing so Raging Bull is at an inherent disadvantage in the list” subjective. Or “There’s no way I’m ever putting Avatar in front of The Apartment no matter what someone says about form” subjective.

Anyway, “objectively” I think the greatest film is a race between Citizen Kane and The Passion of Joan of Arc. It’s not like the group tailing behind behind like Apocalypse Now, 2001, 8 1/2, Stalker, Barry Lyndon, The Godfather, Persona, Marienbad, Vertigo, Tokyo Story, etc. is definitely worse so much as these two are kind of on their own planet when contrasted with their fellow competition and release time, like they each came from a cinematographic monolith the aliens dropped on humanity to push the medium forward by decades. Second part of the reasoning is that I spend the whole movie with my jaw on the floor because the cinematic top standard that the movie has set is never compromised in any scene, an exercise in perfection, whereas some candidates like Vertigo and The Searchers do have these cinematically less interesting scenes. Vertigo’s Midge apartment or antagonist office scenes jump to mind especially, standard old Hollywood filmed theatre that could be from a Cukor film with added color theory where Welles would have otherwise came into the scene with a creative transition from the previous and played with the lighting, obstructed the frame, and/or put an extra effort in the blocking in deep focus. Third part of the reasoning is that I think they make full use of the cinematic arsenal with mastery over nearly each and all of camera movement, photography, editing, mise-en-scene where a candidate like Tokyo Story does away with two of the aforementioned aspects and it hurts its case a bit in comparison. That leaves the candidates like Apocalypse Now and 8 1/2 who do excel in every aspect but as I was hinting at before, stand out less against their respective peers and competition. Maybe if they had the luck to come first they would have done the same, but to be honest when I watch Touch of Evil and I still see Welles moving decades faster than everyone like he’s trying to emulate the tracking shots and camera movement of Boogie Nights 40 years in advance with crap technological means and the usual budget issues, I come to the conclusion that there’s no luck and circumstances and he’s just a genius prodigy in the way the great Coppola/Hitchcock/Bergman,etc. aren’t quite. He’s a shaker in a way perhaps only Kubrick compares, personality issues and resulting filmography aside. And Dreyer only with Joan specifically.

So yeah overall I’m quite consensual with TSPDT-like lists on the question. Of course these are only my personal criteria, and I certainly have a bias for visual beauty. Films like Eisenstein I typically value less, no matter how much I’d like to pretend I’m being objective. And Bicycle Thieves would not come close to top 20, nothing against it but I still cannot understand how it can land so high on here and Cinema Archives with such a big gap with Rome Open City and Umberto D (both at a more predictable spot) and the way I understand the formal criteria. There’s a reasoning I’m missing. I think something like Barry Lyndon bodies it in every way outside historical importance and influence which is not really of intrinsic nature (and didn’t save Rome Open City in the ranking anyway).

Favorite films would be Three Colors: Red, The Passion of Joan of Arc, Last Year At Marienbad, Eyes Wide Shut, Persona, My Night At Maud’s, Barry Lyndon, Apocalypse Now, The Third Man, Red Desert, Vertigo, 8 1/2, La Jetée, The Trial (not quite a movie but hey), Satantango. There’s some overlap but it’s not a 1:1 with the other list (notice Kane isn’t there thus far), and really not an attempt at ranking strictly formal and technical greatness. Subject matter and themes are important to my personal appreciation and love of the medium. Still, I respect the effort for a huge list with rigorous “neutral” methodology.

I’m so glad to see Citizen Kane getting its due regard. I think Citizen Kane is the most underrated movie of all time, since almost everyone except critics and directors call it overrated. I have not yet seen The Passion of Joan of Arc – its probably the best movie I haven’t seen. While I understand you’re reasoning, I do strongly disagree with “making full use of the cinematic arsenal” as a criteria for the #1 – which seems an arbitrary preference for “encyclopedic” or “epic” filmmaking. And in any case, there is no movie that uses cinema “fully”, if you count every specific stylistic flourish used in every movie (e.g. fades to red instead of black), and even choosing not to say, move the camera, is still a choice.

2001 is my personal #1. In some ways, its more understated than Citizen Kane or Joan of Arc (few long takes or rapid cuts; restrained camera movement; no dissolves) – more Tokyo Story. But the sheer visual beauty. It’s the most beautiful movie ever made, the greatest mise-en-scene achievement in history, the best ever use of color, hauntingly beautiful in every frame (maybe not the conference room scene – but does that lowered intensity make the monolith more dramatic?). The Dawn of Man sequence is more beautiful than Lawrence of Arabia, and that’s just the first 20 minutes. The HAL shutdown sequence, and the “Beyond the Infinite” sequence might both be the most beautiful in cinema history.

I also think The Shining deserves to be ranked up with the all-time greats. I’ve been working on a case for it as possible top 10 contender, which is too complex for me to give fully here. The gist: I think the stylistic flourishes are more impressive than Goodfellas, the moving camera aesthetic is some of the best in history, and the form is maybe the most complex and intricate in history. The confrontation in the Coloroda lounge (long take + moving camera with the performances) deserves to be ranked among the greatest moments in movie history, together with the Goodfellas Copa shot, the shootout from TGTBTU, etc. And I think the elevator of blood is my personal pick for the best shot in movie history.

For the record, these are the movies I’ve seen and consider reasonable contenders for the top spot (excluding The Shining): 2001, Citizen Kane, Last Year at Marienbad, The Godfather, Vertigo, Sunrise.

Yes Kane is a victim of its ranking and reputation by now, and mostly liked by students of the craft. Vertigo tends to have more success with mainstream audiences I find, probably because of the color and especially because it has a stronger narrative hook and it’s weirder. But even then, I know a film student who gave a 6/10 to Vertigo and 9/10 to something like Anatomy of a Fall. He did give a 9/10 to Kane but said he wouldn’t have appreciated it nearly as much “if I hadn’t seen a couple of Lubitsch and Capra beforehand to compare”. Makes me wonder what exactly they get taught in film school. The deep focus cinematography and mise-en-scene ideas should be stunning regardless of era or context I would think.

I’d say most people treat the medium as a bastard child of literature with pictures, and are looking to be told stories (Kane is very classical, vanilla and universal by now so “boring”) rather than looking for poetry and craftsmanship in cinematic language. There’s also this weird assumption that the medium improves linearly alongside technology, and a lot of newcomer cinephiles have trouble with the notion of cinematic language changing being more akin to a different artistic movement rather than straight objective improvement, or pre-method acting. So CK having Welles’ theatre buddies as the cast works against it, and scenes like The breakfast table which is a neat editing idea to progress characterization and dynamics in record time look Looney Tunes-ish in execution (tbh I get it lol), and the music is very much of its time too. All this to say, Citizen Kane is fighting an uphill battle against the public of now who race to watch “the greatest film ever made” on the lists and complain when it’s not The Dark Knight or No Country for Old Men, and dismiss the critics as pretentious frauds. The classics that do make it into mainstream appreciation like Psycho don’t really get there because of formal appreciation, it’s because it’s a good serial killer story with a twist and chilling music and atmosphere.

I’ve never been able to connect with 2001 beyond a removed appreciation of its objective qualities. I think I just prefer more character-driven stuff, and Kubrick purposely does away with it in favor of interchangeable Bresson-like humans devoid of demonstrative emotions. The flying magical space baby with music in reference to Nietzsche approaching the planet I have a hard time taking seriously, not unlike the villain in Blade Runner jumping on rooftops in his underwear and randomly grabbing a pigeon so he can use it as symbolism a few minutes later, it takes me out of the experience. I don’t have an issue with it as someone’s GOAT though, its peaks are certainly good enough for it even if I find some scenes a bit static and dull (yes the conference, also when he speaks to the daughter with the planet gif in the window), and it makes A New Hope that came out a decade later look like a sitcom. It’s so unlike everything else at the time that I have to remind myself that it’s a 60s film yet my brain tends to group it with the 70s and 80s unconsciously. Watching the apes… I’m also not too fond of lol…besides the bone edit. I think the Blue Danube montage sequence is my favorite.

Can’t help with The Shining, last time I watched it was like 7 years ago and I was a different watcher then. I did have it behind all of Barry Lyndon, EWS, 2001, A Clockwork Orange and Paths of Glory, but who knows what I would think if I saw it again. I can appreciate a wild pick however, like Declan with The Tree of Life. It would be boring if everyone just always had the same TSPDT ranking slightly re-arranged all the time.

Good to see a fellow Marienbad rep, the fact Drake used to have it as an HR grade made me do a triple take. Easily one of the greatest as far as I’m concerned, each rewatch is like being struck by cinematic lightning and then put in a transe for an hour and a half.

Pingback: The 50 Best Cinematographers of All Time – Scene by Green