“A cinema author should be there to stop others from taking control, not to impose his own will. Wherever the camera turns, that’s cinema.”

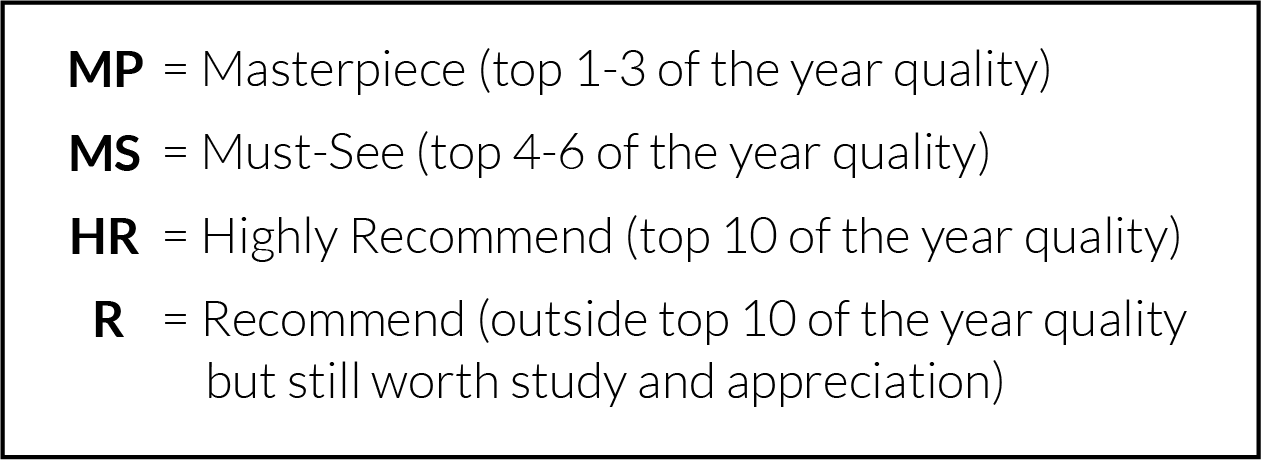

Jean Eustache

Top 10 Ranking

| Film | Year |

| 1. The Mother and the Whore | 1973 |

| 2. My Little Loves | 1974 |

| 3. Santa Claus Has Blue Eyes | 1966 |

| 4. Robinson’s Place | 1963 |

Best Film – The Mother and the Whore

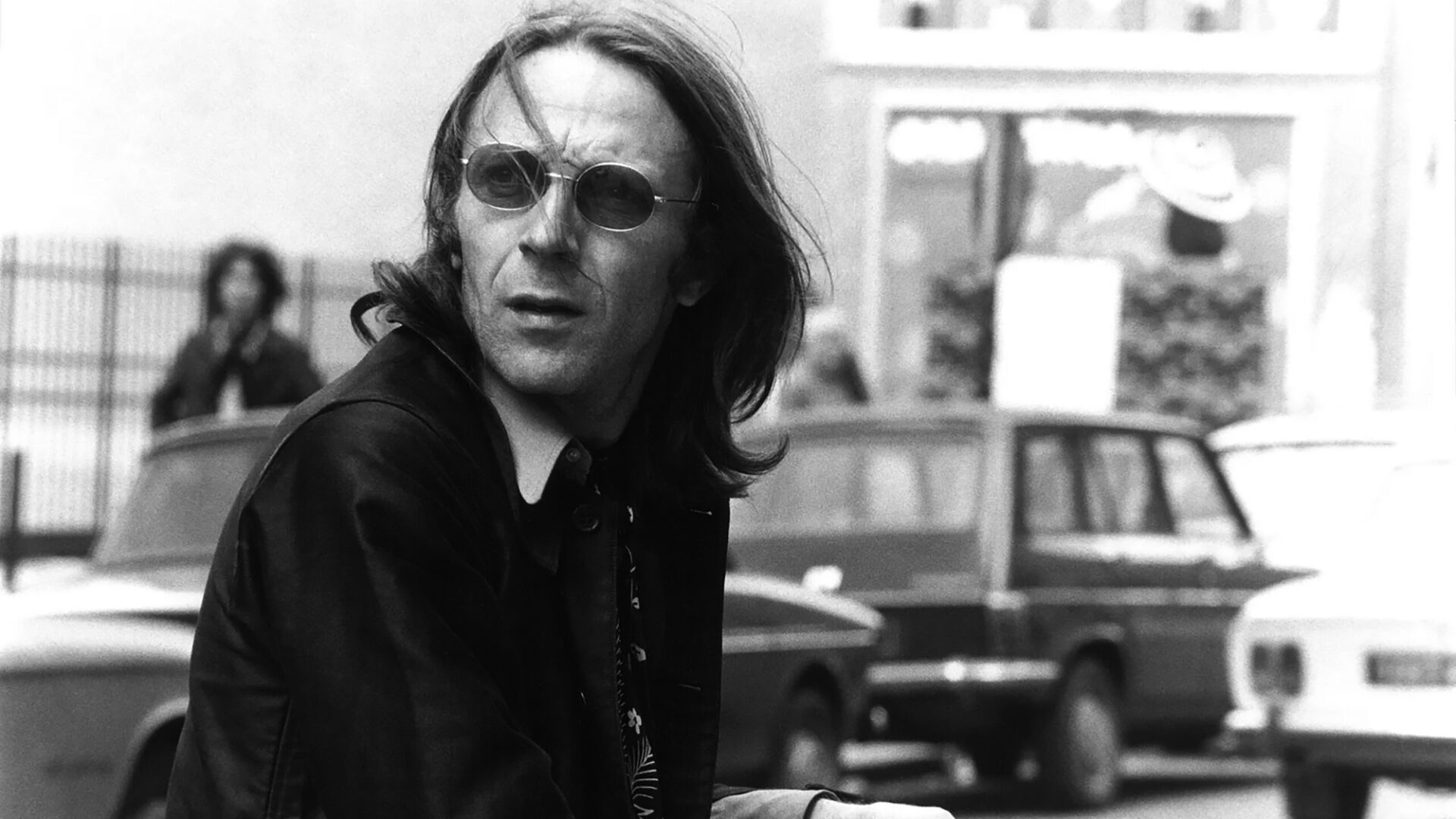

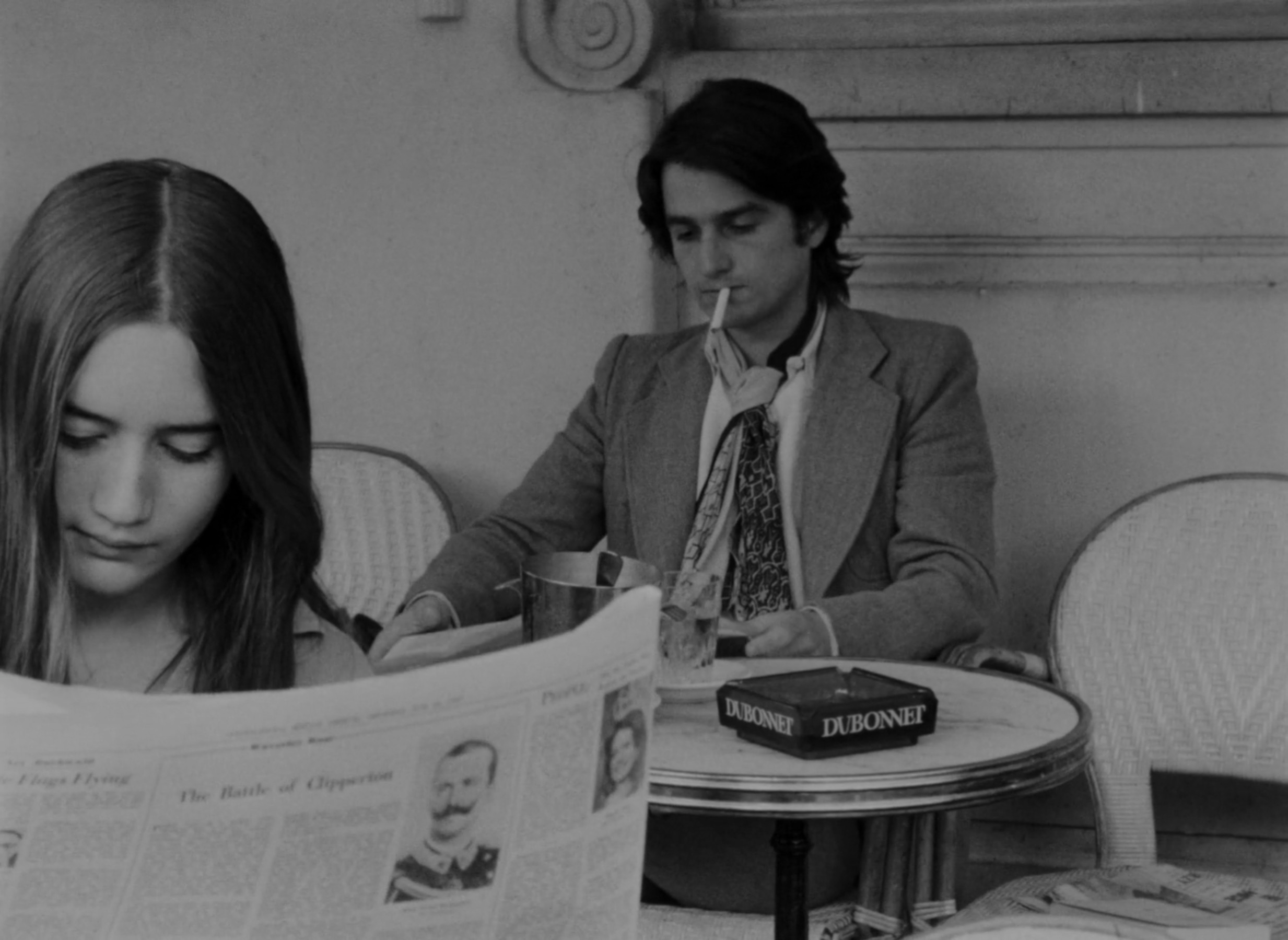

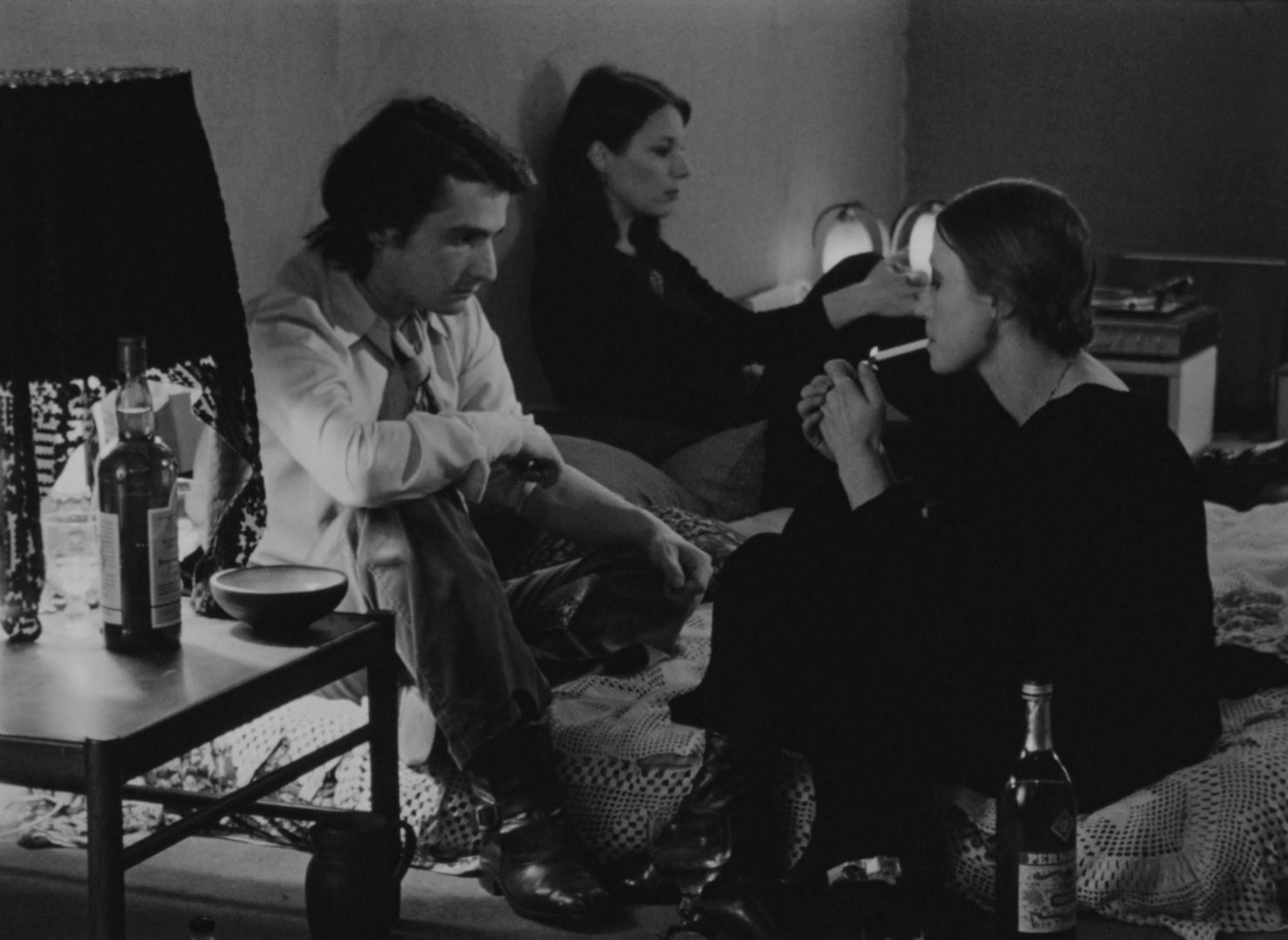

Jean Eustache’s epic drama lays out the Madonna-whore complex in simple terms, placing its young male protagonist in a love triangle between long-term girlfriend Marie and the promiscuous, free-spirited Veronika. As one of the great character studies of the 1970s, it captures this compartmentalisation with deadpan humour and biting cynicism, painting a stark image of manhood stifled by intellectual hypocrisy. Eustache’s mise-en-scène is grimly minimalist, and his camerawork intimate, often lingering on the three lead performances in long, static takes that dwell in the discomfort of their unusual relationship dynamics.

Most Overrated – The Mother and the Whore

TSPDT’s ranking as the 105th best film of all time puts this in high masterpiece territory, which would suggest its visual or formal accomplishment rivals some of the all-time greats. As admirable as these qualities are, it is a couple of hundred spots too high.

Most Underrated – My Little Loves

At #849 on the TSPDT consensus list, it could easily move at least two hundred spots higher. The distant nostalgia that Jean Eustache composes here is not made up of particularly momentous occasions, yet it is in its mundane minutia that the self-discovery of a pre-adolescent boy moving far away from his childhood home unfolds, watching him grapple with the expectations of a restrictive society while seeking to understand his own nascent masculinity.

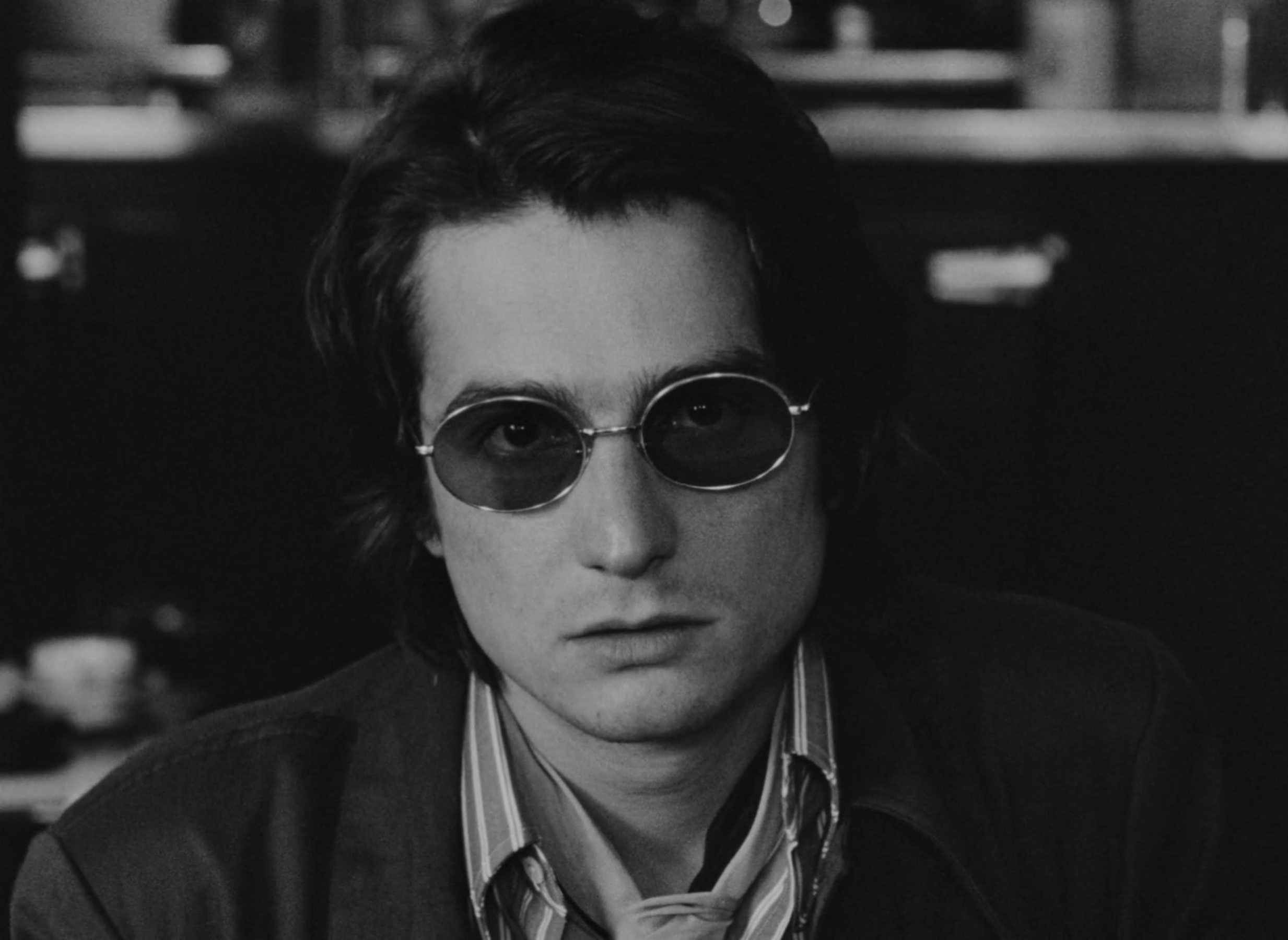

Gem to Spotlight – Santa Claus Has Blue Eyes

Before his two big features, Jean Eustache was laying the groundwork of his gendered character studies with this 47-minute study of identity and desire. Our protagonist Daniel only dons the Santa suit for a bit of extra money as Christmas approaches, but he soon discovers that it his greatest pickup tactic yet, intriguing women who are compelled by the anonymity of the costume – what handsome stranger could possibly be lurking beneath that cheap beard and hat? The moment he reveals his identity to a date amusingly undercuts his inflated ego, seeing them rapidly lose interest. It is a modest entry in Eustache’s brief canon, but nonetheless a fascinating precursor to his greater successes.

Key Collaborator – Jean-Pierre Léaud

In a career as short as Jean Eustache’s, all it takes is a couple of films to be named in this category. Although Léaud is often far more associated with more prolific New Wave directors such as Francois Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, The Mother and the Whore features one of his finest performances, second only to his acting in The 400 Blows. He is given almost four hours here to tease out the insecure, narcissistic character of Alexandre and his toxic Madonna-whore complex. His role in Santa Claus Has Blue Eyes continues to prove the kinship he had with Eustache, who frames Léaud as a younger version of himself in both films.

Key Influence – François Truffaut

Jean Eustache picked up The 400 Blows’ conception of coming-of-age dramas and ran with it, even casting its star Jean-Pierre Léaud as a surrogate version of his younger self. The fleeting moment where Léaud’s character stops by a poster of that exact film in Santa Claus Has Blue Eyes is amusingly self-referential, though Eustache also very much emulates the naturalism and irreverence of Truffaut’s work, similarly taking his camera to the streets of Paris and experimenting with narrative form.

Cultural Context and Artistic Innovations

Experimenting through Shorts (1963-66)

Jean Eustache was the little brother of the French New Wave, getting his start in the Cahiers du Cinema offices after marrying a secretary there, and soon finding mentors in Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut. He did not come out swinging with a culture-defining debut like Breathless or The 400 Blows, but rather spent several years honing his skills on smaller scale projects, even making a cameo appearance in Godard’s film Weekend.

There are two featurettes which stand out in this period, both interrogating the insecurity which lies beneath images of self-confidence projected by young men. The first is Robinson’s Place, following two male friends who are divided over their love for the same woman, compete for her affection, and ultimately unite in cruel revenge when she turns them both down. Their self-entitlement would carry over into Santa Claus Has Blue Eyes as well, introducing another protagonist desperately trying to disguise his total lack of integrity, though the pity that Eustache holds for these characters also points to himself as their prime inspiration. These are sad, lonely men who lack the capacity to properly express themselves, trying to project carefree attitudes that mask deep bitterness.

Eustache adopted Truffaut’s distinct naturalism in these films, shooting on location throughout the streets of Paris to infuse them with an urban grit, and even using Kodak film stock donated by Godard to shoot Santa Claus Has Blue Eyes. This penchant for capturing authentic moments would extend to his work in documentaries as well, though it wasn’t until the 70s that he left his footprint on cinema history.

Developing through Features (1973-74)

Having drifted around the edges of the French New Wave for around a decade, Eustache eventually fell victim to creative block, before the idea for his first feature film suddenly struck him in 1972. There was no holding back his immense ambition at this point, using the nearly four-hour runtime of The Mother and the Whore to apply an intensive focus to the lives of three young adults and their juvenile struggles in love.

Eustache did not break the trend of French auteurs directly reflecting their own lives and philosophies in their films, though he did display an unusually perfectionistic streak. One of his girlfriends described an argument they had which ended with him immediately sitting down to transcribe it verbatim for The Mother and the Whore’s screenplay, using the real names of the women he based the characters off. Even the apartment which much of the film is set in is his own, drawing an autobiographical connection between art and reality.

Although Eustache was clearly far more capable of self-examination than his character Alexandre, he freely admitted to their shared passions and anxieties. Smugness goes hand-in-hand with insecurity, and it isn’t hard to see how Alexandre’s loquacious brand of intellectual pretence would later go on to shape the characters of Woody Allen and Richard Linklater films, especially considering the gaping chasm that lies between his obnoxious ego and feeble masculinity. It is much easier for him to blame women at large for his romantic struggles than to turn a critical eye inwards, as he shallowly longs for an era with old-fashioned values while remaining ignorant to the fact that he still would have been just as undesirable back then.

The visual aesthetic of The Mother and the Whore is largely a continuation of the black-and-white realism Eustache established in the 60s, though far more ambitious in virtually every aspect. A year later in 1974, My Little Loves diverged significantly with its far less talkative screenplay and astounding colour photography, soaking in the summery warmth of small-town France. Its dreamy vignettes reveal the nostalgia of a man looking back to his formative years, re-examining those tiny moments that exposed him to the joys and complications of adulthood. Here, children are observers of the world who learn through imitation, and consequently reflect the lessons they learn back into it.

Rather than indicting any single male character, My Little Loves composes a thoughtful consideration of the society which defines manhood for boys at an early age, and so Eustache draws from further back in his life than ever before. Like the character Daniel, he too grew up in the French village of Pessac with his grandmother, before moving to Narbonne to live with his mother. As such, it is easy to imagine how Daniel might one day become the leading protagonist of any other Eustache film.

As quickly as The Mother and the Whore lifted Eustache into the public eye, the commercial failure of My Little Loves sunk him again. The late 70s saw him return to documentaries and short films with far less ambitious scopes and visuals, even as they experimentally blurred the lines between truth and fiction. In 1981, he was partially paralysed in a road accident, and shortly after committed suicide by gunshot at the age of 42.

Director Archives

| Year | Film | Grade |

| 1963 | Robinson’s Place | R |

| 1966 | Santa Claus Has Blue Eyes | R |

| 1973 | The Mother and the Whore | MS/MP |

| 1974 | My Little Loves | MS |