Federico Fellini | 2hr 28min

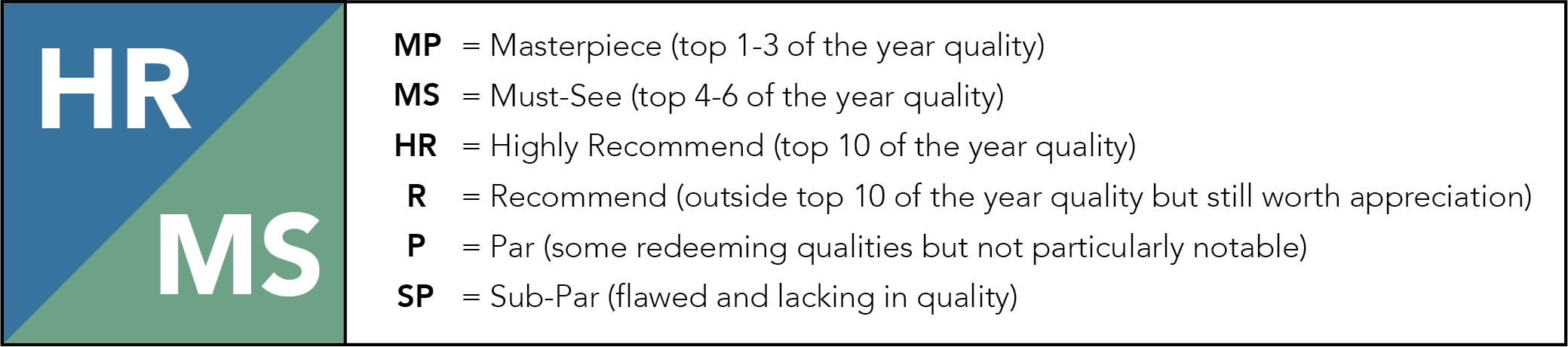

Each time famed adventurer Giacomo Casanova tumbles into another sexual escapade during his worldly travels, his wind-up bird is right there by his side, bobbing and flapping its wings in suggestive, mechanical motions. As both a literal and figurative cock, its phallic shape is not easily missed, casting giant shadows on the wall much like its owner’s. In any other sex scene, in any other film, it would be jarringly out of place – this act is meant to be one loaded with spontaneous passion after all, vulnerably exposing humanity’s most primal instincts. Within the lecherous ventures of Fellini’s Casanova though, this bird is simply an extension of the Venetian playboy’s libido, consistently ticking along like a metronome to Nino Rota’s contrived score of rigid, unwavering synths.

Though based on the memoirs of the real Casanova and his expansive voyage through 18th century Europe, Federico Fellini’s reimagining of his life manifests with demented surrealism, twisting the historical figure into a man trapped in cycles of meaningless carnal exploits. Sex in this decrepit world is not an expression of deep yearning, but rather an imitation of pleasure performed out of obligation, as if trying to convince oneself of an authentic, sensual connection that simply isn’t there.

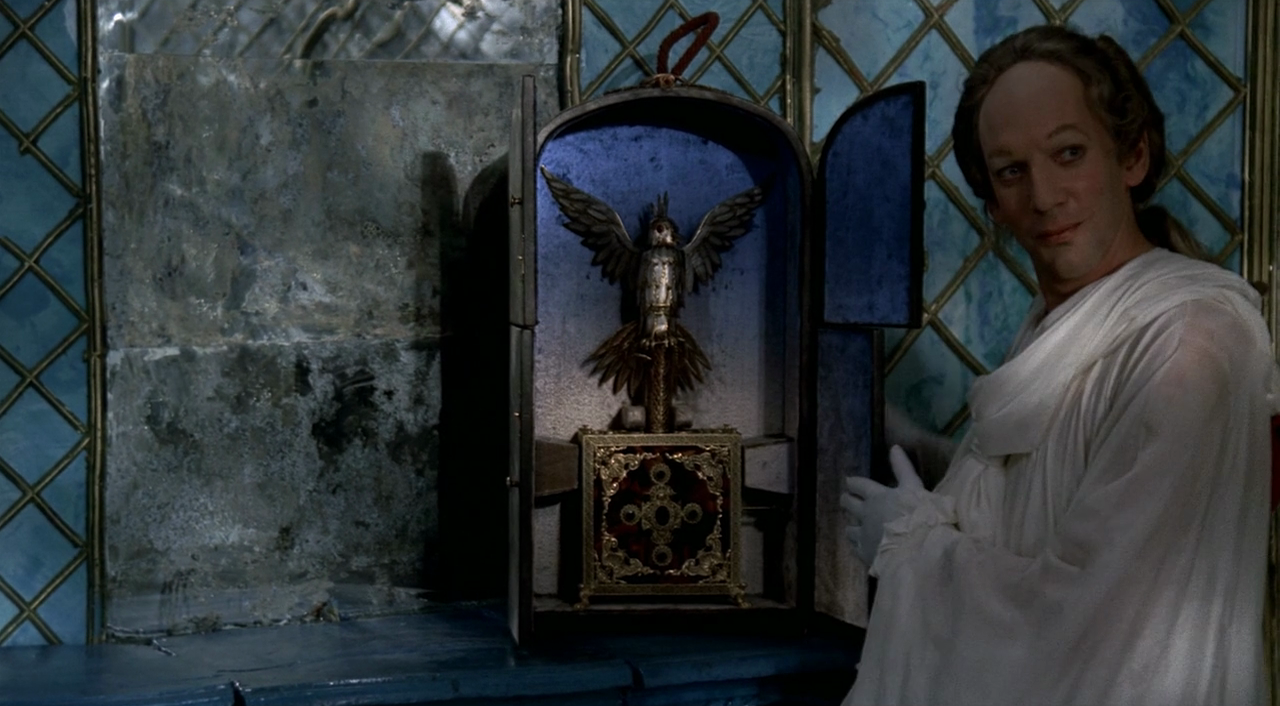

The giant head of Venus which sinks to the bottom of Venice’s Grand Canal in the opening scene becomes a symbolic reminder of this too, returning in the film’s final scene beneath the frozen surface to illustrate the abiding death of everything the goddess of love represents. In her absence, lovemaking is dispassionately chaotic. Coital partners seesaw in the most untitillating manner possible, while Fellini’s camera rocks and zooms in jerky motions as if synchronised to the ensemble’s outrageous acting.

Even outside of these scenes Casanova does not mark a significant achievement for Donald Sutherland, and yet his effeminate, foppish spin on the great Venetian adventurer nevertheless fits perfectly within Fellini’s garish scenery, thinly concealing a deeply insecure ego. After all, it is not his sexual vitality, but his intellectual pursuits as “a poet, philosopher, mathematician” which he would rather be known for – but if his prodigious reputation for bedding women is to be his legacy, then who is he to deny this extraordinary talent?

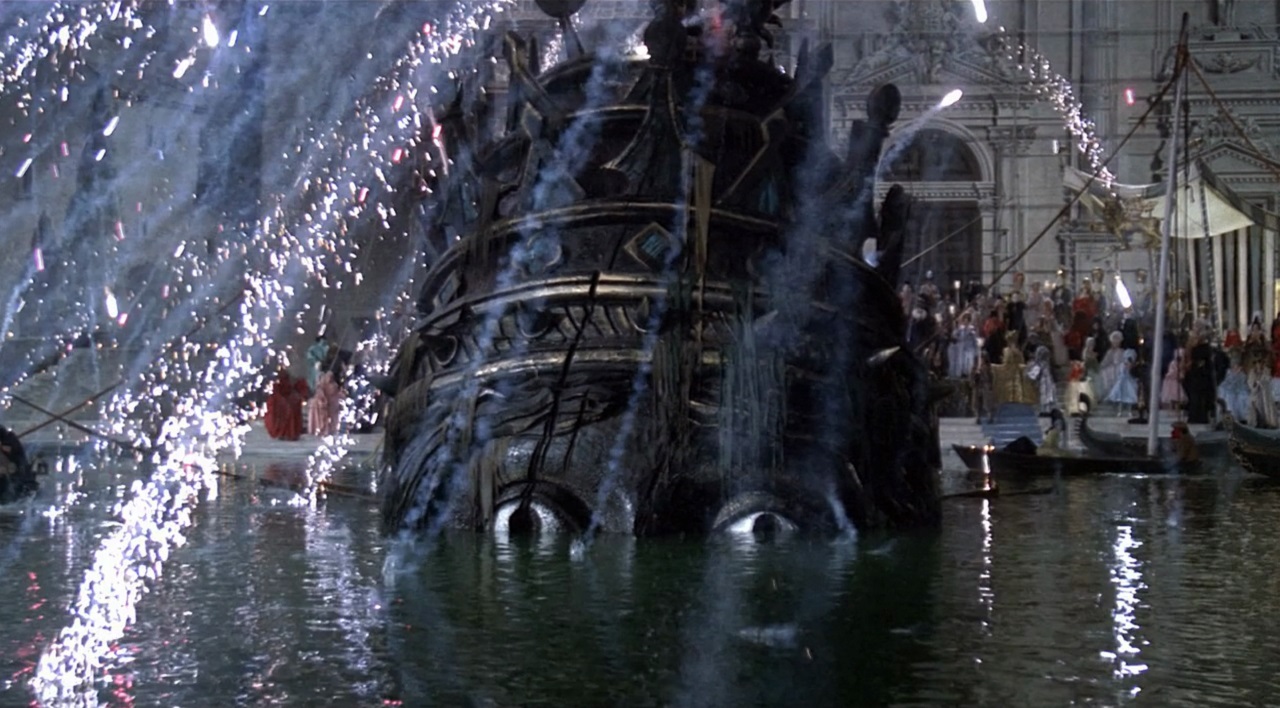

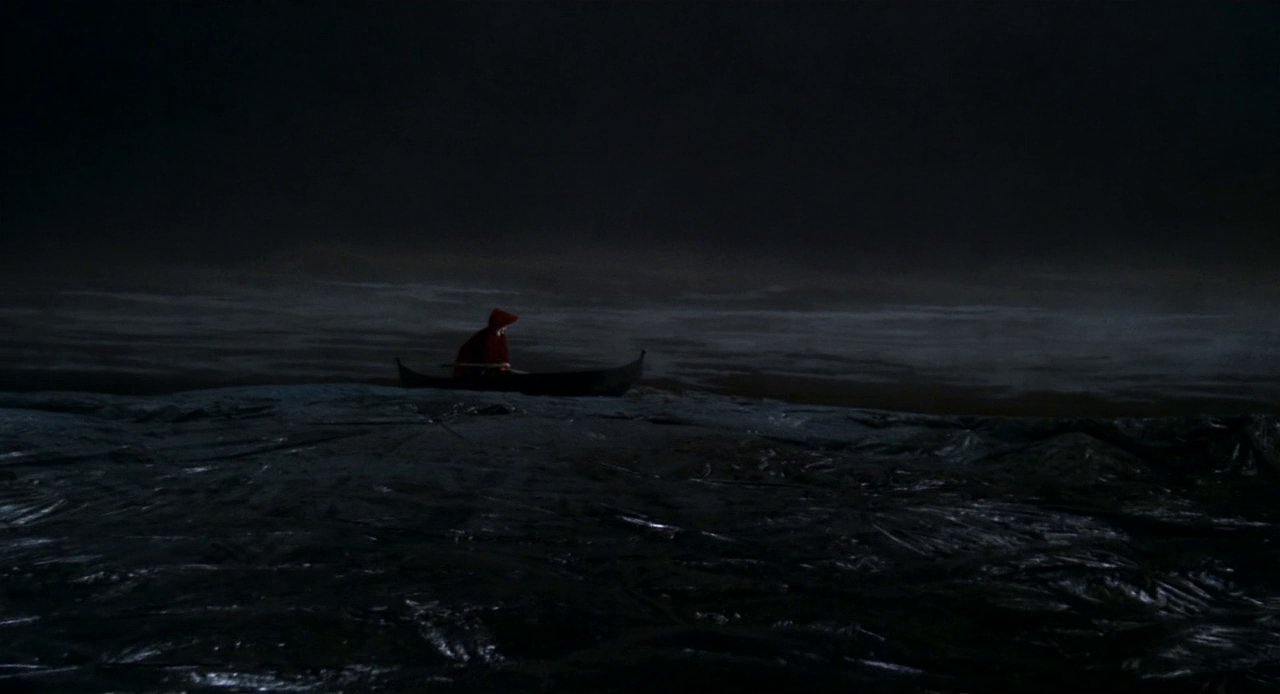

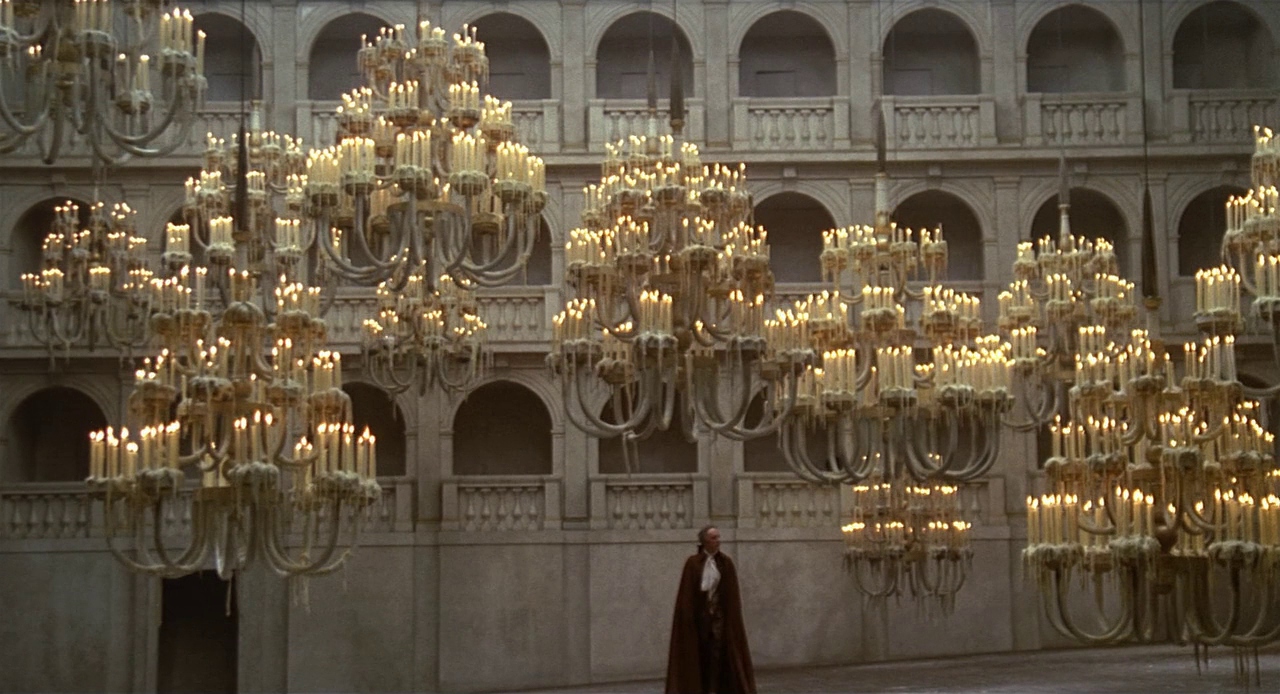

By the time Fellini adapted Casanova’s autobiography in the mid-1970s, he was no stranger to reshaping classical texts and historical eras with lurid experimentation, frequently sacrificing narrative convention in favour of episodic vignettes. As such, Fellini’s Casanova bears especially close resemblance to his cinematic interpretation of the Ancient Roman text Satyricon, which similarly journeyed through warped, theatrical landscapes that never seemed to feel the touch of natural sunlight. Casanova’s excursion to a Venetian island where a wealthy voyeur pays to watch him sexually perform lays the brazen theatricality bare in the opening scenes, sailing his boat across a black sea of billowing tarp, while his convergence with civilisation brings astoundingly anachronistic renderings of 18th century high society. Fellini carries a Sternbergian sense of unruly excess here as he clutters his colourful mise-en-scène with candles, statues, and exorbitantly large plates of food, painting Baroque portraits of overindulgence fuelled by an insatiable emptiness, and curating cinematic galleries of incredible orgiastic anarchy.

In Rome, Casanova is invited to the patrician palace of the British ambassador, where a deranged party of obscene games demeans the surrounding historical art that once signified class and decorum. There, his pretentious attempts to wax lyrical philosophy are met with bewilderment, and to curry favour he instead participates in a contest with a peasant to determine who can sexually perform the most times in the space of an hour. In London, he attends a hypnotically gloomy Frost Fair on the River Thames, where he moves on from the suicidal grief of losing his girlfriend to another man and instead pins his new obsession on a royal giantess. Later in Württemberg he attends what is meant to be “the most beautiful court in Europe,” and yet which rather appears as a haywire nightmare of insane aristocrats wreaking havoc, while musicians fill the air with a dissonant cacophony emerging from the pianos and organs hanging off the walls.

The disconnection between these wandering vignettes somewhat hurts the overall form of Casanova, and yet this detachment also serves to underscore the wistful isolation at the core of Sutherland’s performance, elevating the moment where he discovers what he deems true love. It is during his adventures in Germany that he meets Rosalba, a life-sized mechanical doll who dances stiffly with the voyager like a ballerina in a music box, and whose only objection to his sexual advances is a silent, pained grimace. She is a bastion of unchanging purity in this world of absurdist mayhem – a clockwork contraption not unlike Casanova’s metal bird who reflects his desire for fastidious control over his emotions, relationships, and libido.

Clearly little has changed in the decades that pass between their awkwardly romantic tryst and Casanova’s retirement from travelling, choosing to take up the role of librarian in a cold, draughty Bohemian castle as he approaches the end of his life. Still he attempts to impress audiences with dull poetry recitations, and still he is ridiculed for his pomposity, leaving him to retreat in shame to his darkened chamber where dreams of waltzing with Rosalba upon an icy Venetian lagoon await. As Rota’s music box motif tinkles a soft, metallic melody for the last time, they rotate like tiny figurines, eternally frozen in plastic. There, at the end of this traveller’s long life, Fellini finally reveals the impossible fantasy which has eluded him through many cities, parties, and romances – the frigid, lifeless embrace of a woman as hopelessly inhuman as him.

Fellini’s Casanova as currently available to purchase from Amazon.

Pingback: Federico Fellini: Miracles and Masquerades – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Directors of All Time – Scene by Green