Federico Fellini | 2hr 7min

Spring arrives in the Italian village of Borgo San Giuliano with white, fluffy poplar seeds floating on the breeze, bearing a striking resemblance to the snow that has just melted away. In summer, school student Titta relishes the warm weather on a family day trip to the countryside, with his Uncle Teo being granted short-term leave from the psychiatric hospital where he resides. Autumn later brings cooler temperatures, and sees the vast majority of the population sail out on boats to witness the passage of the ocean liner SS Rex, while winter’s frozen grip on the small town heralds sickness and tragedy in Titta’s family.

The year that passes over the course of Amarcord is not bound by plot convention, and yet each vignette has its formal place in the eccentric portrait of 1930s Italy that Federico Fellini sentimentally models after his own childhood. Unlike the wandering odyssey of Satyricon or the pseudo-documentary of Roma, Amarcord never falters in its lively, easy-going pacing, loosely building its episodic formal progression around the seasonal changes and communal traditions of these villagers’ mundane lives.

Perhaps then we must look even further back to I Vitelloni for the closest comparison in Fellini’s filmography, similarly trapping young men within cyclical routines that connect them to a larger community and hamper their dreams of escape. Like his 1953 hangout film, the camerawork here is dynamic, gliding and panning in breezy tracking shots that gently soak in the remarkable scenery. Even then though, the difference between Fellini’s early neorealist-adjacent style and the vibrant surrealism of Amarcord is gaping, as if his own nostalgic reflections have grown more playfully distorted with age. Characters here slip into dreams with careless abandon, dwelling on fables that infuse Borgo San Giuliano with its own spectacular mythology, and distant fantasies that may only ever live in their minds.

Little do these people know, they themselves will one day become legends to be wistfully recalled by a grown Titta in years to come as well, colouring in the vibrant ensemble of his life with effervescent idiosyncrasies as they rotate in and out of Amarcord’s narrative. Much like Saraghina from 8 ½, the town’s beach-dwelling prostitute Volpina becomes a subject of fantasy for Titta during his adolescent sexual awakening. Local hairdresser Gradisca is conversely a far more untouchable beauty, frequently drawing stares in her shapely red dresses and hiding a loneliness that delicately parallels Titta’s own discontent. The Grand Hotel where she is rumoured to have slept with a prince also plays host to a tall tale propagated by food vendor Biscein that comically details his wild night with 28 foreign concubines, while the long-suffering town lawyer perseveres through the heckling of neighbours to relay this village’s culture and folklore directly to the audience.

The absolute persistence of ‘Mr. Lawyer’ in offering a scholarly perspective on Borgo San Giuliano is amusingly at odds with its pragmatic, free-spirited people, and it is telling that he is the one of the few to regularly break the fourth wall. “Theirs is an exuberant, generous, loyal, and tenacious nature,” he kindly elucidates, describing their proud heritage that runs “Roman and Celtic blood in their veins.” His appearances are intermittent, yet his self-aware monologues work powerfully to divorce Amarcord from the naturalism it occasionally leans towards, sweeping us into the subjective realm of memory where Fellini is at his strongest as a filmmaker.

Nino Rota’s endless variations of the film’s main theme capture this whimsy with carnivalesque panache as well, and are absolutely crucial to the sensitive evolution of each scene. The motif swoons on strings as the camera romantically glides through a frozen tableau of soldiers, forms the jazzy underscore to Titta and his friends’ waltz with imaginary women in the foggy darkness, and even passes diegetically to a musician playing his flute in a barbershop. Its joviality is resilient, never quite losing its optimism even as it fades out with the village lights dimming at night, and ultimately becoming a pure expression of the town’s own flamboyant character.

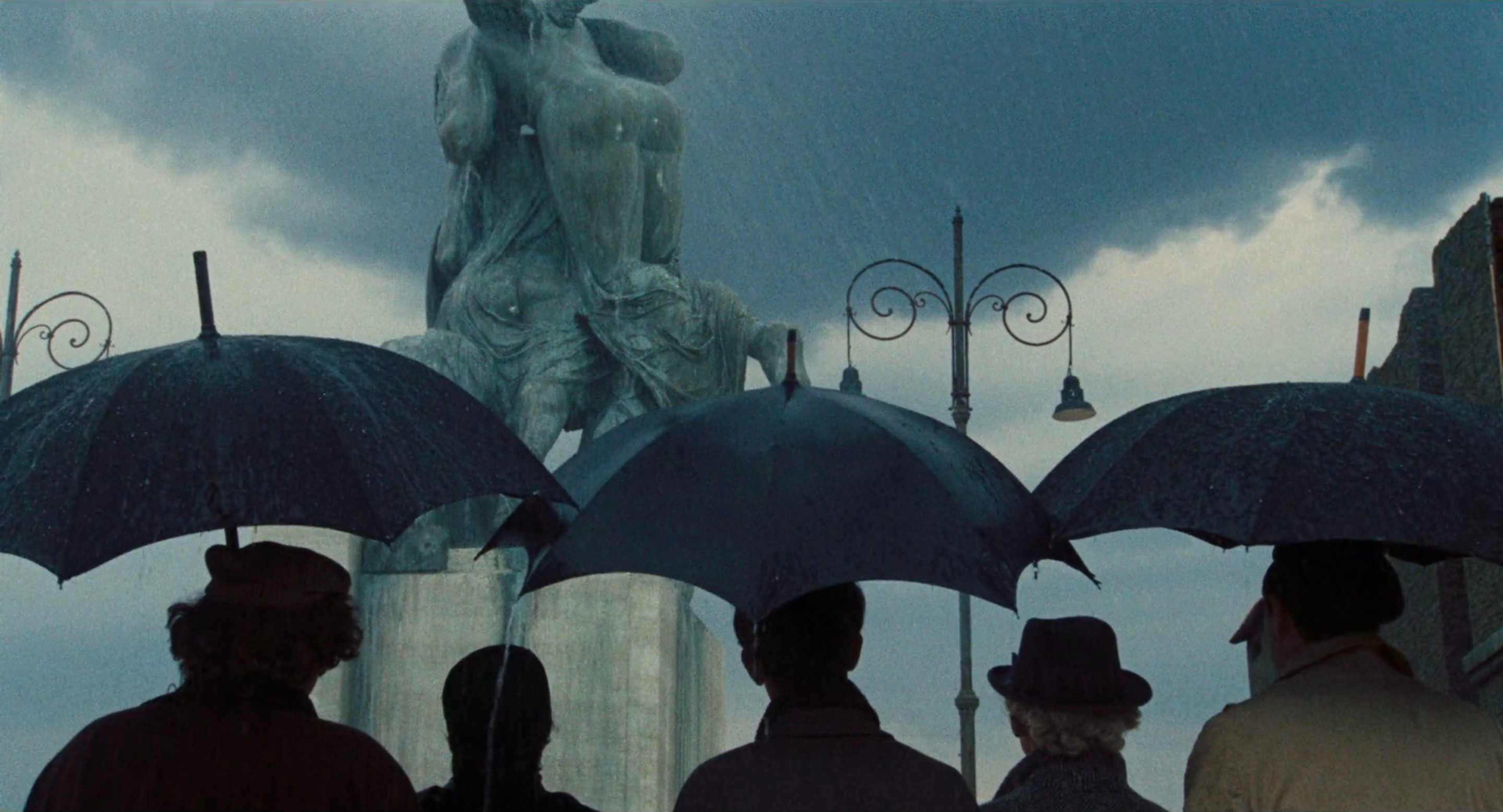

It is quite remarkable as well that every street, building, and monument of Borgo San Giuliano is entirely constructed on studio sets, allowing Fellini a level of control over his handsomely offbeat mise-en-scène that captures a specific era in an isolated region of Italy. At the same time, the scale of Amarcord’s production is enormous, transforming this village into an entire world – which of course it is to an adolescent Titta. The cultural and historical detail woven into the architecture is particularly rich, though Fellini also chooses opportune moments to subtly let authenticity slide for a more wistful evocation of his hometown of Rimini instead, cutting out sharp shadows and silhouettes in his low-key lighting. Even the Victory Monument which stands in its square is recreated with impressionistic elegance, baring the backside of a woman that draws the lustful gaze of visitors, while the small addition of angel wings elevates this voluptuous figure to a level of divinity that exists only in Fellini’s memory.

In those moments of surrealism where this narrative departs from reality altogether, Amarcord moreover reveals a pointed, satirical edge aimed towards the nationalistic tyranny bearing down on Italy’s younger generations. When Mussolini comes to town, the red-and-white papier-mâché model of his face that is raised in a formal procession is laughably cartoonish, and even begins speaking when Titta’s lovestruck classmate Ciccio imagines it marrying him to his crush, Aldina. Suddenly, this military ceremony transforms into a wedding before our eyes, and the fascist pageantry is defanged as red, green, and white confetti is joyously tossed over the underage newlyweds.

Fellini continues to send up the stern teachers at Titta’s school and the church’s ineffective Catholic priests with mischievous glee as well, and yet he is also delicately aware of the malice which lurks within these institutions. There is no comedy to be found in the local authority’s torture of Titta’s father for making vaguely anti-fascist remarks, nor in their chilling speeches of “glowing ideals from ancient times.”

With baggage like this attached to otherwise cheerful memories, maybe it is best for them to remain in the past, Fellini contemplates, though not without sparing a sad thought for those like Gradisca who were carried away by the cultural norms of the era. She may have been the subject of many fantasies in her eye-catching red, black, and white outfits, but she is still a woman with her own hopes and insecurities, revealed in fleeting glimpses behind her veil of cool, feminine confidence. Perhaps then the loneliness which brings her to tears one night in front of a crowd is also what spurs her to marry a fascist officer in the final scene of Amarcord, even as her own fate beyond the inevitable fall of Italy’s totalitarian regime is left sorrowfully ambiguous.

She is evidently not the only one leaving Borgo San Giuliano with dreams of brighter futures either. As the camera slowly pans with the remaining wedding guests across the countryside, their distant shouts offhandedly mention Titta’s departure with little elaboration. Given the recent passing of his mother from an infectious illness though, it isn’t hard for us to surmise the reason. The winter months have wreaked devastation on his family, and their funereal grief has been absorbed into yet another communal ritual carried out with depressingly rote perseverance.

Still, time continues to traipse forward, seeing spring’s puffballs replace the glacial winter snow and old memories give birth to new beginnings. Escaping the routines that govern this community need not arrive as a grand epiphany, but may even be as subtle as a silent, unremarkable departure, leaving one’s name to be fondly recalled by those who have stayed behind.

After all, within Fellini’s portrait of evaporated childhood, memory moves in both directions. Distance across time and space may erode our physical connection with old friends, yet those relationships are revived in the mercurial oceans of nostalgia. Just as the past wistfully lingers in the present, the present sways the past, constantly remoulding it into new forms that reveal previously hidden truths. Only through Amarcord’s reality-warping hindsight can Fellini recognise the absurd norms of his youth with the nuance they deserve, from the oppressive evils and mournful insecurities of his neighbours, to the sweet, boundless joys that have faded with the encroachment of adulthood.

Amarcord is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, is available to rent or buy on Apple TV, and Amazon Video.

Pingback: Federico Fellini: Miracles and Masquerades – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Screenwriters of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Film Editors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Cinematographers of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Directors of All Time – Scene by Green