Federico Fellini | 2hr 9min

Through the lens of our contemporary world, the past often looks like an alien civilisation, abiding by absurd customs and exotic fashions conceptualised by some bizarre foreign entity. Though Federico Fellini acutely identifies traces of modern decadence in his distorted refraction of Ancient Rome, this is the position he maintains throughout Fellini Satyricon, while slowly revealing an even more audacious statement at the heart of its manic weirdness. It is not merely our distant ancestors who are aliens to an impartial outsider, but humanity itself, bound to the same trivial obsessions and primal impulses across history. This age of decadence we live through today is merely an echo of many others that have come before, Fellini posits, each time heralding a socioeconomic decline brought about by gluttonous appetites and egos.

This landscape of widespread moral corruption is of course not unique in his filmography, especially given that Satyricon and La Dolce Vita both trace the journey of two lone men through episodes exposing Rome’s shameless depravity. Where Catholic iconography and ethics guided the narrative of Fellini’s 1960 masterpiece though, Satyricon’s tales draw directly from ancient pagan beliefs, and specifically the eponymous novel penned by Roman writer Petronius as a satire of Greco-Roman mythology. More specifically, this text directly parodied the majestic heroism and fantastical adventures of Homer’s Odyssey, which by the 1st century AD was several hundred years old. While its lost segments somewhat hinder Fellini’s interpretation from mustering up much formal rigour, there is still an immense dedication to epic storytelling on display within the picaresque narrative chaos, reassembling the remains of a decaying world that is only barely hanging together.

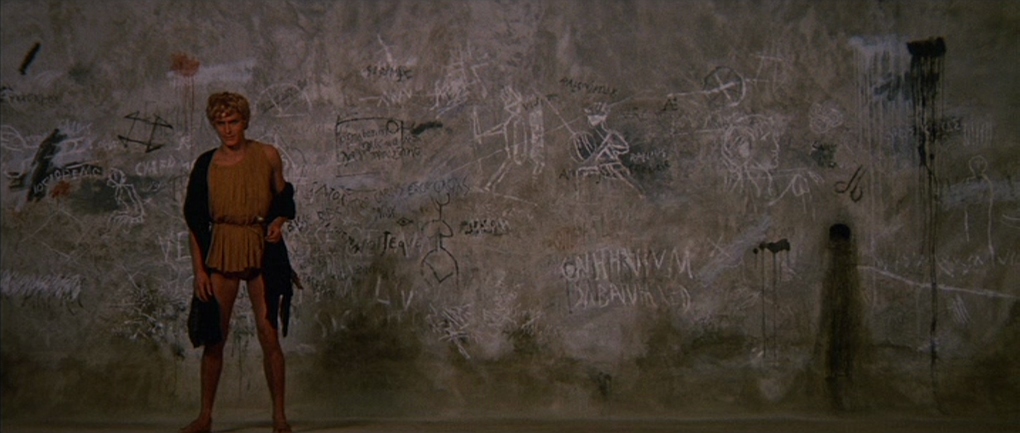

In place of the brave, charismatic hero that Odysseus typified in the Epic Cycle, Encolpius represents a far more ambiguous protagonist in Satyricon, motivated more by epicurean pleasure than love or honour. This is a man who will slaughter a temple of worshippers and kidnap a hermaphroditic demigod in hope of a obtaining a ransom, and yet who is also incompetent enough to carelessly let them die of dehydration in a scorching desert. He does not stand out from this moral cesspool, but rather blends in with its depraved surroundings, feebly falling into the off-kilter orbit of egocentric patricians, lecherous merchants, and bloodthirsty spectators who seek nothing but their own gratification. Given the self-indulgent behaviour of the Roman gods, it is fitting that their followers should celebrate them with such blatant acts of hedonism, transforming their once-glorious empire into a carnival of violence and debauchery.

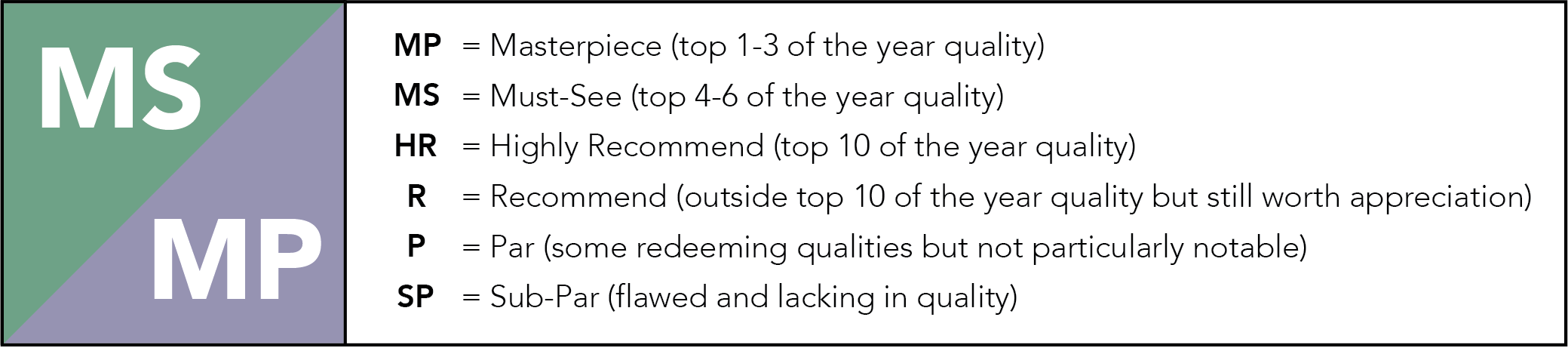

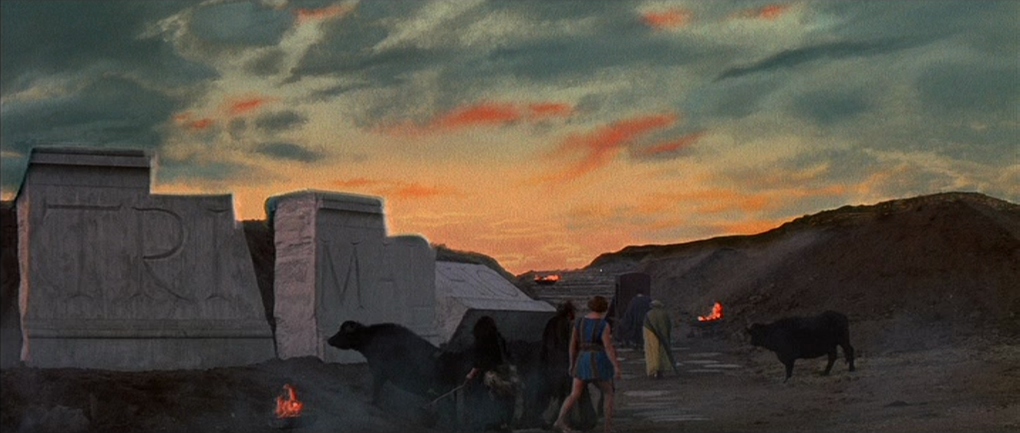

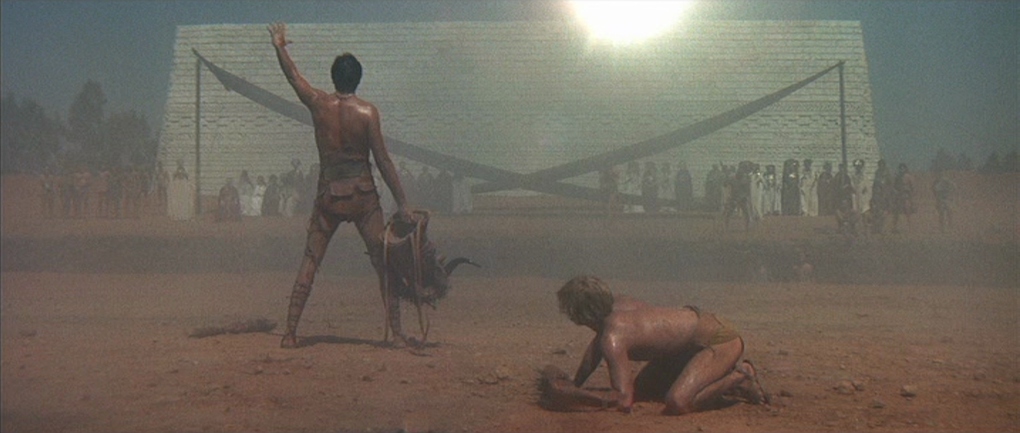

Now fully consumed by his love of Technicolour photography, Fellini doesn’t hold back either in his frenetic visual recreation of Satyricon’s Rome, especially with genius cinematographer Giuseppe Rotunno joining his troupe. This is expressionistic world building at its most imposing, based around colossal, anachronistic sets that might almost belong in a theatre were it not for their vast expansion in all directions. The giant ziggurat of apartments where Encolpius lives with his slave and lover Gitón towers menacingly in the darkness above a grey courtyard, and of course to reach it from the other side of the city one must pass through a brothel where strange sexual acts unfold in full view of the public. Where 8 ½ and Juliet of the Spirits once blended reality and surrealism in fragmented dreams, Fellini immerses Satyricon in a feverish hallucination that has taken over the lives of the Roman people, and even infected the skies with a deep red that casts the land below as an infernal underworld.

It is no coincidence that some of Fellini’s most demented imagery arrives with the novel’s most famous episode, set at a banquet held by wealthy freeman Trimalchio for the entertainment of the commonfolk. Encolpius has been invited by his new friend, the eccentric poet Eumolpus, and as they venture towards the meeting place they come across an absurdly confronting sight – a hundred nude men and women waiting outside in a giant, steamy bath, surrounded by an even greater number of candles. The erotic of nature of Fellini’s blocking here is crucial to the carnal madness of Satyricon, bringing together bare bodies in uncomfortably intimate arrangements which simultaneously satiate and disturb the senses.

Inside Trimalchio’s gaudy manor, he continues this staging as guests lounge around the edges of the room in extravagant costumes and makeup, imprinted against red walls and enveloped in thick clouds of steam. Insanity reigns when the crowd frenetic dances to dissonant live music and organs spill across the floor from a giant roast hog, yet Fellini’s focus never wavers from the codependent relationship between the narcissistic host and his guests. Supposedly based on Emperor Nero, the insecure Trimalchio holds these lavish parties for no other purpose than to be adored by the commonfolk. He is evidently little more than a talentless, egotistic fraud using his wealth to gain respect, though his patience is short when they do not play according to his rules, even having Eumolpus tortured in the furnace for calling out his plagiarised poetry.

“In my house, I’m the poet!”

These characters are not actively engaged with the political climate of Ancient Rome, yet at every turn Fellini is placing Encolpius’ fate in the hands of more powerful men. The few times he does take an active role in his own story, his efforts are rapidly undercut by the turmoil of a crumbling world, whether depicted literally in the earthquake that violently tears down his home or the insurgents who install a usurper as their new emperor.

That Encolpius is the closest thing to a Greek hero that Imperial Rome has to offer is pathetic indeed, making for a comparison that only cuts deeper in Fellini’s bastardised recreation of King Minos’ Labyrinth and its fearsome Minotaur, seeing our protagonist escape only by begging for his life and confessing that he is no Theseus. Through Satyricon’s retelling of the Widow of Ephesus myth, Christian doctrine does not entirely escape Fellini’s scathing satire here either, though his most direct parody is reserved for the final minutes where Eumolpus requests for his body to be devoured by the beneficiaries of his will.

True to the source material which records this as the final scene, missing segments notwithstanding, Fellini abandons his narrative mid-sentence with Encolpius leaving on Eumolpus’ ship to Africa. It is difficult to label this an anticlimax when we were never promised a great catharsis to begin with, though by taking a step back to reveal Satyricon‘s characters painted in frescoes upon ancient ruins, Fellini breaks the immersion to acknowledge that plot was never paramount in this absurd dreamscape. Cinematic surrealists like David Lynch and Alejandro Jodorowsky would later centralise this tenet in their own filmmaking too, adapting archetypes and allegories with a subversive, Felliniesque irreverence that believes greater truth lies in the fanciful stories we fashion from skewed perceptions of our past rather than history itself. Through its surreal blend of modern art and classical antiquity, Fellini Satyricon not only examines this grand paradox of truth and fiction – it becomes a direct embodiment of our most maddening psychological conflict, farcically recognising the indelibly primal self-contradictions of humanity across all ages.

Fellini Satyricon is currently available to purchase on Amazon.

Pingback: Federico Fellini: Miracles and Masquerades – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Film Editors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Cinematographers of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Directors of All Time – Scene by Green