Federico Fellini | 2hr 17min

Coming off the heels of his widely acclaimed triumph 8 ½, it seemed that Federico Fellini was done with neorealism. By delving into the fantastical dreams of a surrogate character, he had constructed a kaleidoscopic self-portrait of immense depth and ambition, while shamefully exposing his own infidelity to the world. As such, his next project Juliet of the Spirits essentially held up a feminine mirror to 8 ½, contemplating the other side of his marriage to Giulietta Masina and filtering it through an equally surreal lens. It shouldn’t come as a surprise then that he derived Juliet’s name from his wife’s, and additionally cast her as the spurned housewife whose entire identity has been defined by her relationship to men. In fact, it isn’t even until Juliet’s husband Giorgio arrives home in the first scene that her face even appears on camera, having up until then been concealed by camera movements, obstructions, and shadows conveniently rendering her non-existent in his absence.

By the time Juliet of the Spirits was released in 1965, it had been eight years since Masina’s previous collaboration with Fellini, having last starred as jaded prostitute Maria in Nights of Cabiria. Now with a few extra lines on her face, she carries a mellow wisdom in her round, dark eyes as Juliet, saddened but not embittered by her husband’s extramarital affairs. The whispered name “Gabriella” first piques her suspicion one night when he is sleep talking, and the multiple phone calls that come through with no one on the other end only feeds it, sending her to seek out the services of a private detective who might provide answers. None of this can take away from the fact that Giorgio has been her “Husband, lover, father, friend, my home,” but even now as she lists everything she is losing, she does so with a wistful smile.

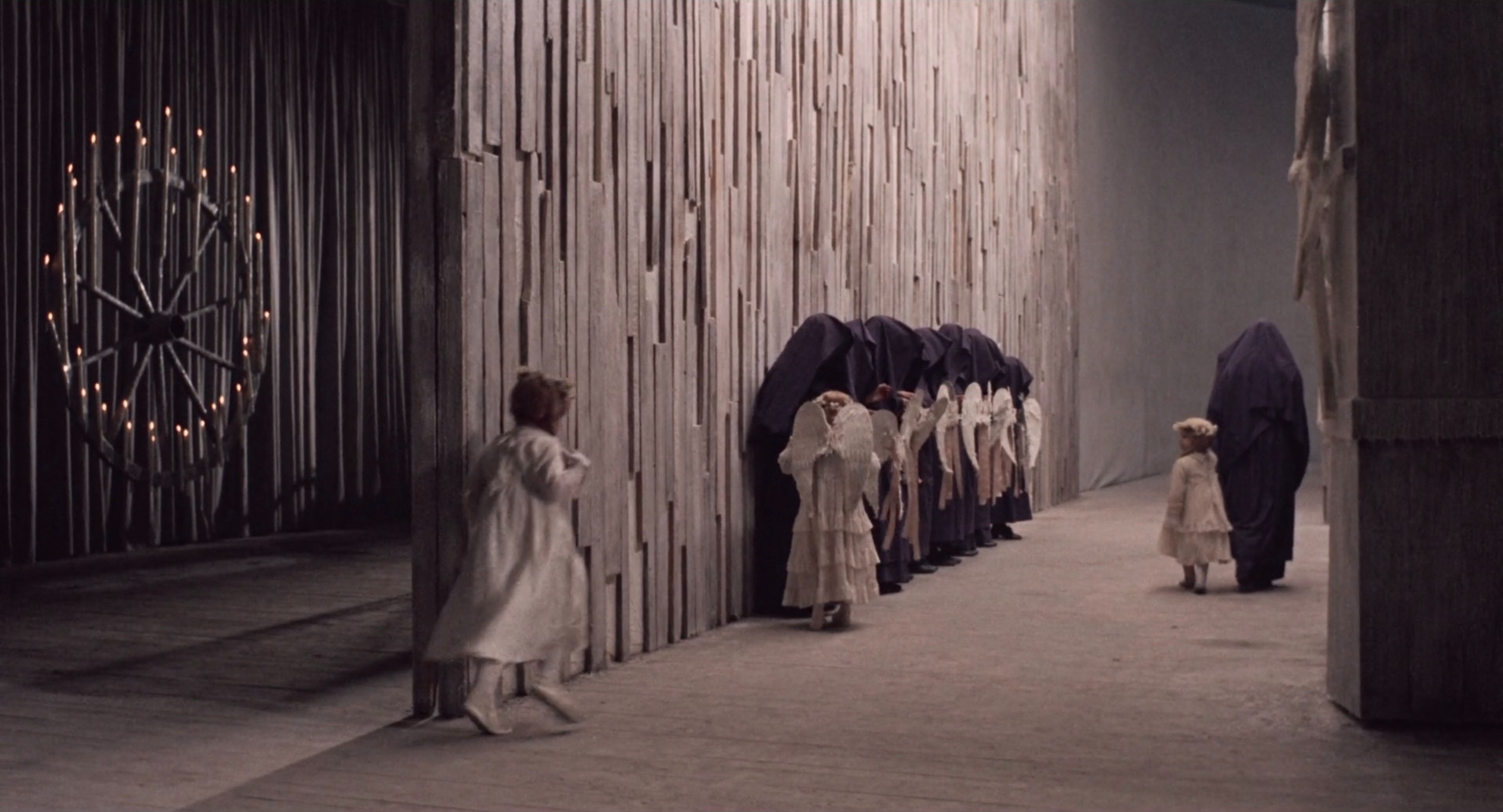

Though Juliet tries to explore facets of her suppressed identity through an assortment of vibrant costumes, within her home she is most often garbed in chaste white tones, while guests light up the mise-en-scène with purples, greens, and pinks. Most of all though, it is Fellini’s radiant crimson hues which dominate his palette in Juliet of the Spirits, opposing our protagonist’s virginal neutrality with a sexual passion considered dangerously out-of-bounds. With so many clashing visual elements, his production design is deliriously chaotic, yet also flamboyantly united under an aesthetic that blends circus-like extravagance with regal Baroque architecture in varying proportions. While Juliet’s lavish, upper-class house is adorned with lighter tones, Sylva’s grand manor makes for a magnificent recurring set piece, each time hosting an orgiastic fever dream of wild hedonists revelling in rowdy opulence. Further bringing these extraordinary settings to life is the slow, dollying movement of Fellini’s camera too, peering through the multicoloured gauze curtains draped around Sylva’s bed as it slowly drifts past, and dollying in on actors with dramatic grandeur.

This bold venture into Technicolor filmmaking is no doubt a breathtaking visual achievement for cinematographer Gianni Di Venanzo, but even more crucially it commences Fellini’s trajectory into manic expressionism, evocatively painting out his characters’ reminiscences and hallucinations. For Juliet, these only really begin taking over her life following a séance on her fifteenth wedding anniversary, conducted by the gate-crashing friends of her husband who has entirely forgotten the occasion. From there, the spirits Iris and Olaf are summoned into her life as conflicting voices in her mind and surreal visions interrupt her reality with increasing ambiguity, beginning with a dead raft of horses and a sunken tank of studly weirdos dredged up from the ocean.

With Juliet’s stream-of-consciousness voiceover often running through her life and dreams though, fortunately not all these visions are so impenetrably abstract. Many of these fragments are rooted directly in childhood memories that have become foundational to her identity, unfolding like reveries distorted by decades of distance and Fellini’s purposefully disjointed editing. In particular, her recollections of a circus and a pageant play formally mirror each other as a pair of theatrical performances sitting on either side of a moral divide – one being a gaudy spectacle of feathers and sparkles that satiates the senses, and the other starring Juliet herself as a virgin martyr being executed for her faith.

In the former, Fellini constructs a visual extravaganza that pays homage to Italy’s rich tradition of performing arts, and the seductiveness of this lifestyle that lured her grandfather into an affair with a beautiful dancer. The career he had built as a respected professor was thrown out with this decision, and by the decree of Juliet’s disapproving mother, so too was his relationship with his family. As he runs with his mistress towards a stunt plane, each of these figures chase him from behind, playfully staged in a long shot that evokes Ingmar Bergman’s ‘Dance of Death’ from The Seventh Seal. It is clear to see here how infidelity has impacted Juliet’s life once before, and yet quite curiously her feelings towards her philandering grandfather are far more positive than those towards her controlling mother, who in her mind represents an unattainable standard of self-righteous morality and untouchable beauty.

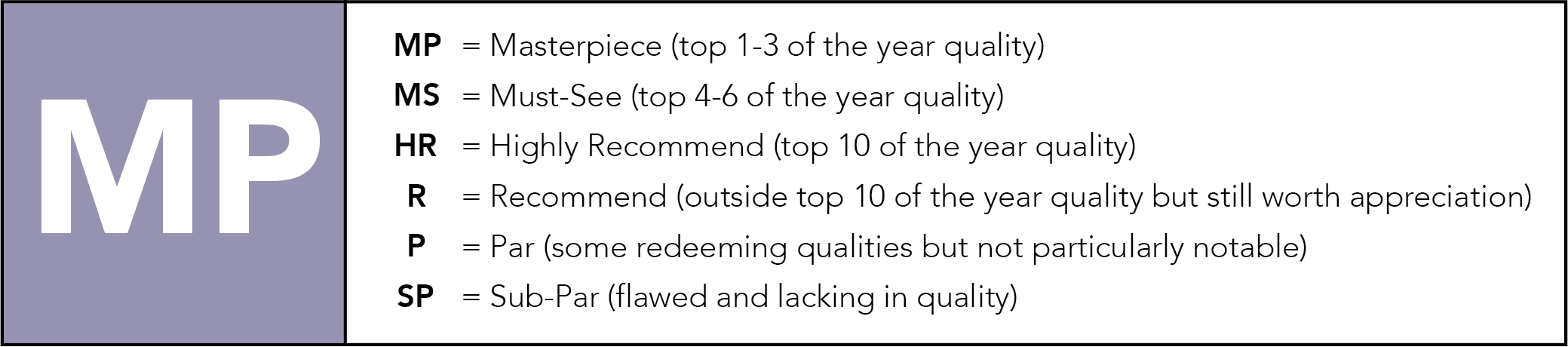

In comparison, Juliet’s pageant play arrives as a far more modest affair, surrounding her with spectral nuns in purple hooded cloaks who planted the seed of Catholic guilt in her mind. As she watches her child self be sacrifice on a pyre of paper flames and lifted to the heavens, the adult Juliet similarly recites her lines, and perhaps even finds some inspiration in them – “I don’t care about the salvation you offer me, but about the salvation of my soul.” As it is though, both versions of Juliet have essentially been sacrificed to society’s gender expectations and forced to become a virginal Madonna, serving men as a sexless, maternal figure.

While Juliet’s hallucinatory flashbacks begin as self-contained vignettes, each one introduces spirits that linger through her waking life, tormenting her with obscure reminders of her psychological self-doubt. Just as she is about to give up her marital vows and have sex with a guest in Sylva’s manor, the camera swings down from the reflection of their romantic liaison on the ceiling mirror to reveal the horrifying image of a demonic girl in white robes, roasting above a fire. Whenever Juliet feels she is straying too far from her morals, that demonic vision of her younger self from the play arouses a disturbing guilt, while nude women hiding around her bedroom conversely laugh and sneer at her insecurity.

To complicate the conflicting pressures further, Fellini challenges Juliet’s belief in Christian salvation with a mixture of pagan alternatives, including the aforementioned séance, an Egyptian rite of passage, and an oracle named Bishma who is said to enlighten those who are lost. Speaking in a raspy voice from behind transparent white drapes though, this raving clairvoyant offers nothing but shallow advice to submit to one’s husband, even at the expense of Juliet’s own welfare.

“Love is a religion, Juliet. Your husband is your god. You are the priestess of this cult. Your spirit must burn up like this incense, go up in smoke on the altar of your loving body.”

As for the private detective who represents a more secular approach to seeking truth, there is no doubt that he offers far more practical answers, yet hard proof of Giorgio’s affair does not bring with it the spiritual guidance that Juliet craves. It seems as though every character she meets is following their own path to self-fulfilment, and while many are convinced of their own eminent wisdom, few are able to satisfy her longing to reconcile moral virtue, carnal desire, and holistic enlightenment. By giving tangible form to the intangible Christian God for instance, her sculptress friend Dolores seems close to comprehending the infinite bounds of His grace, and yet Juliet also realises that she has degraded a divine beauty into objects of lust.

“Let’s give back to God his physicality. I was afraid of God before. He crushed me, terrified me. And why? Because I imagined him theoretically, abstractly. But no. God has the most superb body ever. In my statues, that’s how I sculpt him. A physical, corporeal God, a perfectly shaped hero who I can desire and make my lover.”

Even easier still is ignoring the existence of God altogether as Sylva and her hedonistic guests seem to do, encouraging a similar attitude in Juliet. “I fulfil my desires in life. I don’t deny myself a thing,” this glamourous starlet proclaims, and though she is clearly out-of-touch with any spirituality, Fellini does not paint her as a wholly negative influence. The confidence she instils in Juliet is absolutely crucial to her journey, driving her to pursue an independent life that sources happiness from within, rather than from her husband or any religious authorities. It is not that she is afraid of being alone, one American therapist who regularly attends Giorgio’s parties explains, but her only true fear is rather of the happiness she might find in independence that allows her “to breathe, to live, to become yourself.”

That Giorgio is the one to eventually pack up and leave at least eases the burden on Juliet to instigate the separation, though there are no tears to be shed on her part anyway. Left alone, she must venture into her soul one last time, but this time not to confront any new memories or insecurities. A small, previously unseen door in her bedroom wall opens up, and against her mother’s demands, she enters to find a long, narrow corridor. There, her inner child is strapped to that flaming grill, alone and scared. Finally untying the ropes that have kept her bound to society’s scalding judgement all these years, she lets her run free, right into the arms of the man her mother had kept her from all these years. “Farewell, Juliet,” her grandfather warmly imparts. “Don’t hold me back. You don’t need me anymore. I’m just another one of your inventions. But you are life itself.”

As present-day Juliet walks outside the large white gates of her home, so too does she find liberation from its persistent spirits. Suddenly, new voices she had never heard before begin speaking to her, coming from a deep sense of self-acceptance rather than the nagging judgement of others. There is no aggressive expressionism or cluttered opulence to found in the green, natural expanse that she walks into, and much like the final seconds of Nights of Cabiria, Masina’s eyes once again drift towards the fourth wall in poignant recognition of our presence in her story. With a simple glance, Juliet takes control of her narrative, finally escaping into new beginnings away from the imposing gaze of society, religion, and Fellini’s own prying camera.

Juliet of the Spirits is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.

Pingback: Federico Fellini: Miracles and Masquerades – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Female Performances of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Female Actors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Edited Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Film Editors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Shot Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Cinematographers of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Directors of All Time – Scene by Green