Radu Jude | 2hr 44min

The first layer of irony that surfaces in Angela’s job of casting workplace accident victims for an ‘occupational health and safety’ video arrives with understated derision. Contrary to the claims of the corporation commissioning this project, many of their personal anecdotes directly implicate their own employer. For the company, this culpability is irrelevant – it is much easier to feed them scripted lines advocating for their colleagues to wear proper safety equipment, implying that they are the ones at fault. But really, how would a helmet have saved the fatigued, overworked woman who slipped off a walkway, broke her spine, and ended up in a wheelchair?

The second layer of irony that Radu Jude weaves into his black anti-capitalist comedy Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World comes through its overarching portrait of the woman tasked with capturing these stories, quietly suffering under similar conditions as she drives across Bucharest from one location to the next. Angela is no doubt aware of these parallels as she reaches out with compassion to the people she is filming, but at the end of the day she is just another employee who must adhere to the company’s strict guidelines and hustle culture. If she must miss out on a break to get the work done, then so be it. If the executive should insincerely wish that she isn’t working extra hours to complete this project, then she is to meet them with an equally disingenuous response.

“Oh no, for this one no, of course not! Only eight hours, don’t worry.”

In both her job and her professional attitude, Angela is reluctantly complicit in upholding the company’s façade of accountability, while she and the rest of Europe’s working class continue to be exploited by the out-of-touch elite. Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World may be set in the modern day, but as far as Jude is concerned this is simply the progression of a slow, cumbersome apocalypse, with the title itself being attributed to a man who witnessed some of the twentieth century’s greatest atrocities firsthand. Polish Jewish poet Stanisław Jerzy Lec foresaw the fall of humanity arrive not through earth-shattering destruction, but rather the creeping dystopia of the banal, herding the middle and working classes into unending routines of mindless frustration.

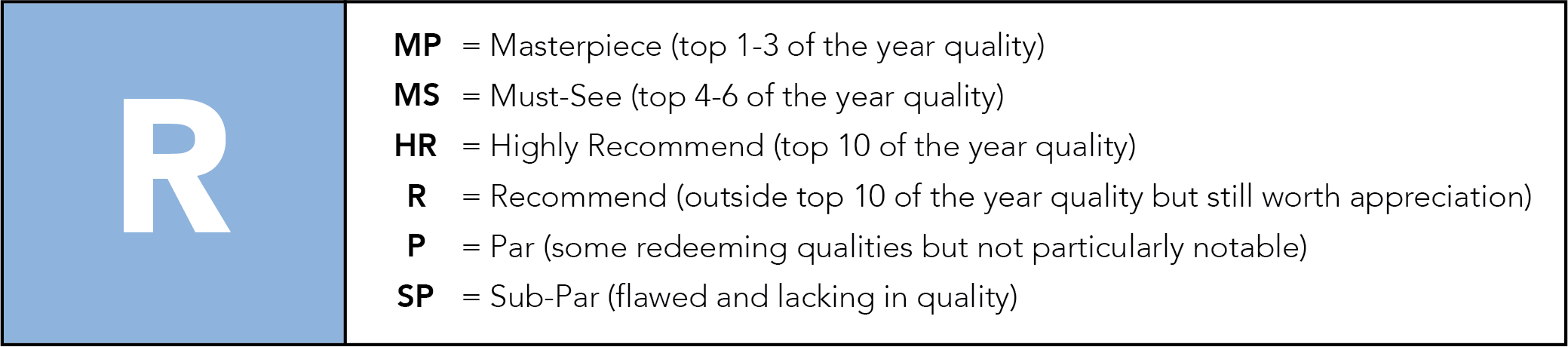

The arthouse influence of Jim Jarmusch’s deadpan humour, measured repetition, and solemn greyscale photography is considerable here, as Jude commits Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World to a minimalist formal structure that finds absurdism in the mundane. His shots are largely static and last several minutes at a time, sitting in the passenger seat of Angela’s car as she throws insults at other drivers and blares music to keep herself awake. Outside the window, blurs of Bucharest’s fountains, railways, and shops are intermittently brought to a complete standstill by traffic jams, while Jude’s jump cuts underscore the mind-numbing gaps of time that lie between one point of absolute inertia and the next.

Jude’s ambitious attempt at building out the form of his piece into a sprawling indictment of the daily grind becomes a little messier when his focus shifts from away Angela, cutting in clips from a 1982 Romanian film following a taxi driver with the same name. Their routines vaguely line up, and the parallels he is drawing between their struggles are clear, though without a real arc these segments become unnecessary in this nearly three-hour film. The freeze frames and jerky slow-motion he applies to cutaways of the city’s crowds are a little more formally sound, though Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World is often at its strongest when it is studying our primary subject as a low-ranking subordinate of the corporate world.

After all, Angela is not some oblivious drone existing only to serve her superiors. She clings to her individuality with coarse defiance, making the time to balance her own ‘art’ with her work duties. Most obvious and obnoxious of all are those TikTok videos she films as her chauvinist alter ego, Bobita Ewing – a vulgar pickup artist who apparently spends his life partying and travelling the world. In these segments, Jude’s cinematography briefly breaks out into low-res colour, applying a crudely unconvincing filter that gives her a beard, bald head, and monobrow.

Bobita is a blatant parody of every ‘alpha male’ influencer online who spews misogynistic trash to his followers, and even name-drops Andrew Tate as one of his friends. Angela may only be performing this persona in jest, but this is still her channel through which she is able to let loose the rage she cannot express at work, and as such she has few inhibitions about who sees it. “I’m just making fun of things. So I don’t go crazy,” she plainly justifies to her disapproving mother, and when she noisily records one video in a public bathroom, Jude’s wide shot amusingly catches another woman nervously peek her head around the corner to catch sight of this bizarre act.

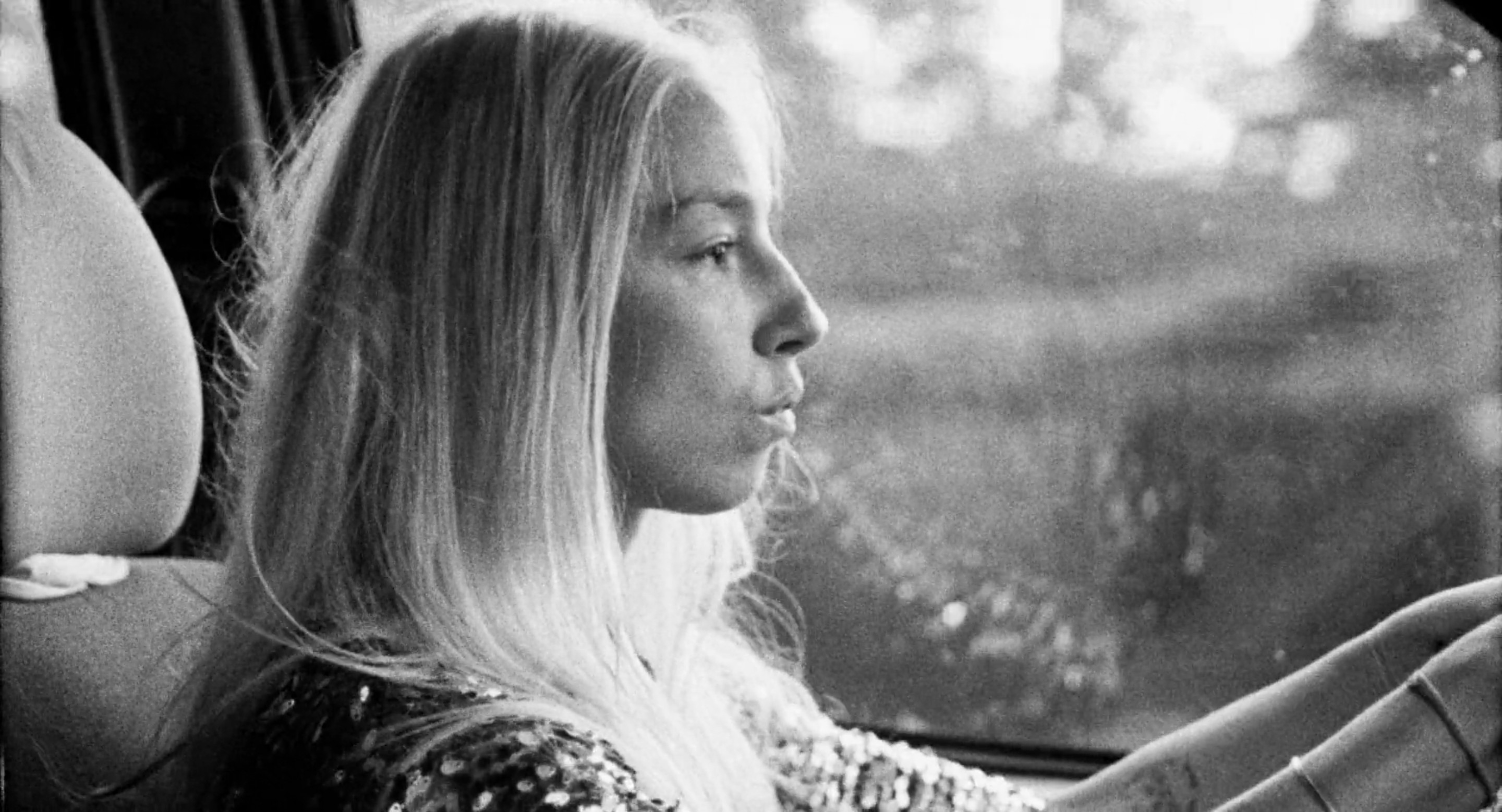

The small detours that Angela makes throughout the day on an already-tight schedule further develop the non-conformist side of her character, especially as she winds up on a film set and finds a kindred spirit in Uwe Boll, notorious director of bad movies. Together, they rail against the limitations that the establishment imposes on creativity, though Jude remains cynically aware of the tasteless, unsophisticated art they are essentially arguing for. When Angela later finds the chance to furtively meet up with her boyfriend during work hours, the two make love in her car, which later forces her to comically cover the stains he left on her dress with an airport pickup sign as she meets a high-profile client. On a more sombre note, she even finds herself at one point contending with a hotel chain that is exhuming her grandparents’ bodies due to a land dispute, adding to the pile of unnecessary stresses wreaked by corporate domination.

With additional references to Queen Elizabeth’s passing, the war in Ukraine, and American gun control, Jude very gradually expands Bucharest’s localised decay into a global dystopia that is pervasively documented in every form of modern media. Angela is unavoidably attached to her iPhone, using it to record videos for both work and leisure that capture different angles of society’s deterioration, just as the taxi driver interludes represent it through the artifice of cinema.

Ultimately though, it is the final act of Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World where Jude’s media collage delivers its strongest blow, baring the microaggressions of corporate exploitation for all to see in a static, unbroken 35-minute shot inspired by Michael Haneke’s own surveillance-like photography. This is the culmination of all Angela’s hard work, with wheelchair bound Ovidiu Buca and his family being chosen to star in the work safety video, while the factory where his accident took place looms large in the background. It matters little that he might have been spared this fate had the metal barrier which knocked him into a coma been made from a lighter material, or at least been visibly marked so that the driver who sent it flying had seen it to begin with. Once again, the blame is laid at his feet. Never mind that the incident took place after work hours as he was heading home – he should have been wearing a safety helmet.

Together, the talent and crew suffer through take upon take, with the director making tiny tweaks each time. To avoid giving ammunition to the “enemies,” the incriminating bar must be moved out of the background, and Ovidiu’s mother must hold his hand at a key point to force a bit of sympathy. Behind the scenes, this film shoot quickly evolves into a mock courtroom drama with Ovidiu’s actual lawsuit against the company at stake, but of course none of this is to be shown in the final product. A ‘creative’ stroke of genius sees them pivot towards copying Bob Dylan’s music video for ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’, with Ovidiu holding up giant, green cue cards to the camera so the editor can insert whatever words they like. “I hope they won’t write anything that might hurt us,” Ovidiu’s mother voices as they wrap shooting, though the director’s words of assurance couldn’t be emptier.

And of course, Angela is still there through it all, recording her Bobita videos without a care for which bystanders may be unnerved by her offensive monologues. The switch to colour in this section also reveals her glittery dress in full, inconsequentially rebelling against the culture of corporate conformity that has a stranglehold over every other aspect of her working life. These dramatic expressions of identity are amusingly trivial, not quite earning Angela our sympathy so much as demonstrating how feeble they are in the grand scheme of civilisation’s dreary downfall. Jude’s narrative may be tightly confined to a single working day, and yet the dismal landscape that Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World stitches together from media fragments stretches far beyond the city of Bucharest, helplessly watching the slow, mechanical grind of modern civilisation into a never-ending traffic jam.

Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World is currently streaming on Mubi.

One of the strongest films of 2023, in my opinion. Formally rigorous and, at the same time, unapologetically wild. Truly a one of a kind work.

There’s room to go higher, I’m just not entirely sold on some of those weaker sections I mentioned. What do you make of the taxi driver scenes?