Federico Fellini | 2hr 54min

Beneath the open, outstretched arms of the giant Christ statue that flies over Rome in the opening minutes of La Dolce Vita, every sin he preached against two thousand years ago is being committed by its self-indulgent citizens. Aristocrats shamelessly fornicate in drunken orgies, greedy journalists overstep boundaries to fill their own pockets, and children’s lives are chillingly taken by those most trusted to protect them. Still, at least these people are willing to pause for a moment to wave at the sacred spectacle blessing the crowds with his abundant grace – or is it judgement he is casting down, condemning them to the miserable hellscape that they have built at the global capital of Catholicism?

Just because gossip reporter Marcello Rubini laments this underworld of fetishised religion and vacuous principles doesn’t mean he is absolved from indulging in the hedonistic lifestyle that feeds it. Though he follows the movements of the flying statue in his news helicopter, apparently not even that is impressive enough to keep his eyes from drifting to the rooftop of sunbathing woman calling out to him. “What’s going on with that statue? Where are you taking it?” they yell, only to be drowned out by the whirring blades. With Marcello quickly abandoning any hope of chatting them up beneath the noise, it would seem the disconnection is mutual, as he flies away to his destination and on with his life.

This is the plague of loneliness which has infected Federico Fellini’s depiction of Rome in La Dolce Vita, distilled into pure allegory. The most basic communication between lovers, friends, and strangers is hopelessly lost in the noise of superficial distractions, stifling the few genuine attempts to find some deeper sense of purpose within an empty life. Like parasites sapping the lifeblood of humans, Rome’s media and celebrity culture are partially responsible for this spiritual epidemic, with Marcello’s photographer friend Paparazzo even being named after the Italian slang for mosquito, and in turn giving birth to the term ‘paparazzi.’

Up to now, Fellini had explored similar moral tragedies within the fables of La Strada and Nights of Cabiria, though for the first time the poverty-stricken woes of the working class are not where his focus lies. Instead, he aims both disdain and conditional sympathy towards the upper end of society where there is a complete vacuum of personal responsibility, while only occasionally noting their impact on the suffering of those below. In true Christian style as well, seven is the all-important number which guides Fellini’s episodic structure, breaking this landscape of false idols into a series of parables that take Marcello ever deeper into Rome’s moral corruption – not unlike Dante’s physical descent into the circles of Hell.

The other key characteristic carried over from Fellini’s previous films as well is his location shooting within Rome itself, building on neorealist tradition while departing wildly from his mentors’ sensitive examinations of post-war poverty. For the first time he is shooting in widescreen CinemaScope, which itself is a fitting choice for this film of eclectic environments and bustling crowds, though his lush depth of field and meticulous blocking across the full horizontal length of the frame lifts La Dolce Vita to even greater stylistic heights that not even Fellini had touched before. At the many decadent parties Marcello attends, the camera frequently sits close to the ground as it observes inebriated guests mill around the bright, modern interiors, while one such gathering inside a Baroque castle treats its imposing history as little more than a consumable luxury. At the same time though, La Dolce Vita isn’t some conservative, high-minded condemnation of modern festivities. Like Fellini, Marcello is both lured in and repelled by its seductive glamour, the paradox of which incites a Catholic guilt that lingers from his childhood.

Beyond the ornate walls of Marcello’s parties, Fellini guides us through busy streets and neighbourhoods crowded with glossy black convertibles, reflecting the lights of Rome’s raucous nightlife. Only the wealthy can afford to live here, right by the majestic historical monuments that become little more than status signifiers, while the poor are kept out of sight on the city’s rundown outskirts. Though not all settings here were filmed in the real locations, such as the studio sets recreating the interior of St Peter’s Basilica and the Via Veneto, the artifice isn’t readily available from the sheer detail of the mise-en-scène.

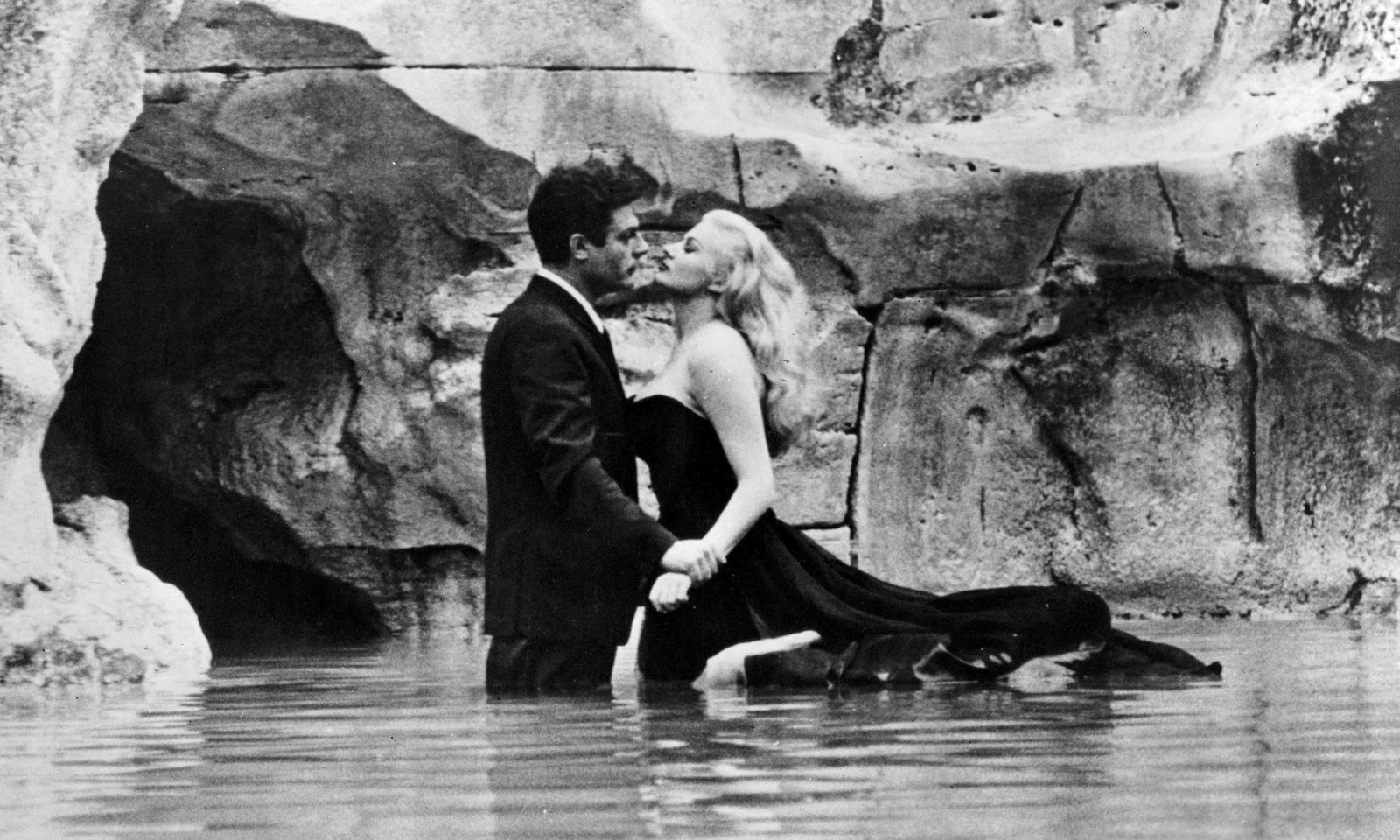

When it comes to La Dolce Vita’s most memorable and iconic scene though, Fellini wisely chooses to use the real Trevi Fountain as the basis of Marcello’s fleeting romance with lively Swedish movie star, Sylvia Rank. Played by up-and-coming actress Anita Ekberg, Sylvia makes a sizeable impact in her relatively short time onscreen, becoming celebrity incarnate with her ditzy public persona, buxom beauty, and moody sensitivity. She may not live outside the superficial glamour of the entertainment industry, but her radiant passion is unlike anything Marcello has encountered before, and so over the course of one night the subject of his gossip column evolves into an icon of angelic veneration.

After wandering away from the party, he and Sylvia approach the Trevi Fountain. She is the first to dance in its waters before inviting him in, where he reaches his hands out to touch her face. Once there though, he simply can’t bring himself to cross that threshold of intimacy. Like the Roman gods carved from stone that stand above them, Sylvia has frozen, as if taking her place among their divine company. She may be revered and even desired, but never must something so sacred be grasped by mortals as spiritually corrupt as Marcello.

Perhaps then wealthy socialite Maddalena might be a more attainable prospect for the cynical journalist, seeing as how her discontent with modern-day Rome mirrors his own. For a time, he tries to cover that up with shallow praises of it as “a jungle where one can hide well,” though her desire to set up a simpler life elsewhere slowly wears away at his false positivity. When they run into each other again at a party hosted in an aristocrat’s castle, he once again wanders off with a woman who has drawn his eye, yet one who this time curiously leaves him in an empty room.

From a nearby chamber, Maddalena speaks into a well, revealing a trick of acoustics that hauntingly carries her voice to where he is seated. It is through this ghostly separation that Fellini plays out what seems to be the most sincerely romantic dialogue of La Dolce Vita, as she confesses her love and proposes marriage. Marcello tentatively dances around his answer for a time before finally returning the sentiment with a heartfelt monologue, and yet it isn’t until he is met with total silence that he realises Maddalena has been quietly seduced away by a fellow partygoer. The tangible vision of potential romance that faded into a disembodied echo has now disappeared entirely, and thus Fellini breaks Marcello’s heart again with another reason to despair.

How can Marcello blame Maddalena though when he too has fallen so many times to the same temptations, even as he has complained of wanting to excise them from his life? His moral offences are not victimless, as throughout the course of La Dolce Vita he continues to cheat on, neglect, and physically abuse his mentally troubled fiancée, Emma. He has a “hard, empty heart,” she claims, while he accuses her of smothering him with a sickening, maternal love. Even at their lowest though, just as it seems they have cut ties for good, there he is picking her back up from where he dumped her on the road. In a more conventional Hollywood film this act might be framed as persevering love, and yet Fellini pierces the glib idealism to expose their reunion as little more than a desperation for companionship, and a passive willingness to let its toxicity eat away at their self-respect.

Delving deeper into Marcello’s inability to maintain healthy relationships, Fellini introduces his womanising father. It is through his sins after all that we gain some insight into the self-destructive hedonism that he passed onto his child, and on an even larger scale, from older generations down to all of Rome. The discomfort that crosses actor Marcello Mastroianni’s face here exposes a new kind of insecurity we haven’t seen before, reluctant to expose a formative piece of his childhood which lacked a stable, loving paternal figure.

At the nightclub where Marcello meets his father, Fellini chaotically fills the frame with the glitzy spectacle of giant balloons tumbling from the ceiling, and draws their lustful eye towards burlesque dancers. It is during one clown’s sad trumpet solo though, incidentally reminiscent of Gelsomina’s from La Strada, that Marcello’s father grows disinterested and strikes up a chat with the woman next to him – his son’s ex-girlfriend, Fanny. His eagerness to cross that line and pursue his own impulsive desire not only speaks to his selfish, weak-willed character, but also offers some explanation for the vices ingrained in Marcello, who at the very least recognises them as such.

Between the seven parables of La Dolce Vita, Fellini continues to trace the path that leads from small transgressions to a larger culture of cruel exploitation, most acutely capturing that evolution in the media frenzy that congregates around a fake sighting of the Madonna. Just outside the city, two children from a poor family lay claim to witnessing this miracle, while their parents spur them on. Marcello is among the more sceptical visitors – “Miracles are born out of silence, not in this confusion” – and yet he follows through on his report anyway, feeding the blind faith of believers to keep the news cycle moving along.

At the tree where the Madonna was sighted, sick people and their families pray for healing into the night, as if desperately trying to reclaim the Christian spirituality that Rome has lost. Fellini positions his camera at high angles above the crowd as rain begins to fall, short circuiting the flood lights and saturating spectators, yet still they all remain. Their devotion might almost be considered inspiring were it not for the mindless fanaticism that escalates when the children claim to witness the Madonna’s return. As they run from one spot to another, Fellini fills his frame with the crowd’s confused, disorderly movements, growing more frenzied until they begin violently tearing branches off the tree that she apparently touched.

Any objective observer can see the blatant irony of their desecration, breaking an apparently holy icon into lifeless parts so they might selfishly take a little bit of it home for themselves, though the scene’s final stinger doesn’t arrive until the following morning when the dust has settled. In the heat of the moment, a small, sick boy has been trampled to death, literally killed by Rome’s religious herd mentality and its corresponding media circus.

After such a reprehensible display of abhorrent human behaviour, there is only one person who Marcello can turn to for some restoration of hope, and whose own storyline is split up into three smaller parts across La Dolce Vita. Affluent intellectual Steiner is the man that Marcello wishes he could be with his balanced lifestyle, loving family, and sophisticated hobbies, and Fellini even sets him up as a spiritual guide of sorts who plays jazz and Bach on a church organ. His party of artists and philosophers is relatively subdued to the others featured in La Dolce Vita, inviting Marcello to thoughtfully ponder his two great passions of journalism and literature, and how he might follow in his host’s footsteps to find peace within himself. In rebuttal though, Steiner is quick to divulge his own discontent.

“A more miserable life is better, believe me, than an existence protected by a perfectly organised society.”

Only when Steiner’s story is wrapped up in its third act do the terrible depths of his anguish come to light with a gut-wrenching twist. Outside his house, journalists gather to get the scoop on the man who allegedly killed his children before committing suicide, and swarm his unaware wife whose confusion turns to horrified realisation of what has happened. “Maybe he was afraid of himself, of us all,” Marcello tries to reason, grasping for answers that don’t entirely make sense in the wake of such immense tragedy. If a smart, self-assured man like Steiner couldn’t hold onto some thin thread of moral order in this universe though, then what hope is there for Marcello?

It isn’t quite clear how much time has passed between this scene and Fellini’s final episode, but the shift in Marcello’s disposition is notable, having abandoned both his passions of journalism and literature to sink deeper into the entertainment industry as a publicist. After he and some new friends break into one of their ex-husband’s beach house, the night quickly devolves into a bacchanalian orgy which sees Marcello cover a female companion in cushion feathers and ride her around the room, degrading her to the level of a beast. No longer do we see any inhibition or hesitation in his debauchery, but rather a listless resignation to his moral depravity that thoroughly blends in with the licentious crowd.

In these closing moments, Fellini formally unites the end of Marcello’s spiritual journey in La Dolce Vita with its start and midpoint, and draws on two crucial symbols from both. As the sun rises the next morning after the party, Marcello and company loiter down to the beach where fishermen have hauled a bloated Leviathan from the water. “It insists on looking,” Marcello reflects as he stares into its dead, godless eyes, feeling them pierce his conscience. Where La Dolce Vita began with Christ flying over Rome, it now ends with Satan being dredged up from its depths, as Marcello finally reaches the innermost circle of Hell and faces the hideous disfiguration of his soul.

And yet even here at Marcello’s lowest point, still there is a divine presence by his side – a young girl he had previously encountered at a seaside restaurant, whose soft features he noted resemble those of an angel from an Umbrian church. In a key piece of foreshadowing, the cha-cha song ‘Patricia’ she innocently hummed along to while waitressing is perversely revisited in the closing moments as the soundtrack to Marcello’s orgy, hinting at her return and final attempt to reach him. From across a channel on the beach where he now stands with his friends and the dead sea monster, she waves and shouts at him, eventually getting his attention.

Ultimately though, Fellini chooses to end La Dolce Vita the same way he started it – with Marcello’s complete failure to connect with others, even as his Umbrian Angel tries to reach him over the noise of the waves. With a defeatist shrug, he returns to his decadent life, and consequently leaves behind the purest icon of divine grace that he has encountered yet. Through Fellini’s cynical subversion of theological iconography, the greatest religious epic put to film does not trace the paths of great men like Judah Ben-Hur or Moses, but a tortured soul’s weary descent to the depths of an amoral, existentialist hell.

La Dolce Vita is currently available to buy from Amazon.

Pingback: Federico Fellini: Miracles and Masquerades – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Male Performances of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Male Actors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Screenplays of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Screenwriters of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Film Editors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Shot Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Cinematographers of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Film Composers of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Directors of All Time – Scene by Green