Roman Polanski | 1hr 45min

By the time Roman Polanski reached his second feature film Repulsion, he had already proved that shooting largely in a single location was no imposition on his creativity. In place of the sailing yacht where class tensions unravelled in Knife in the Water, here it is a London apartment which he distorts into disturbing hallucinations, revealing the chaotic psychological state of reclusive Belgian immigrant Carol Ledoux. The latter two instalments of his Apartment trilogy Rosemary’s Baby and The Tenant would famously enter supernatural territory, but the deterioration of Carol’s mind in Repulsion needs no such influence from cults or demons. The visceral revulsion she feels towards even the vaguest notion of sex is instead enough to cripple her for days, confronting her with intimate violations of mind and body that seek to undermine her sense of personhood, and disintegrate her grip on reality.

Coming off her grand success leading Jacques Demy’s Technicolor musical The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, Catherine Deneuve becomes the vessel through which Polanski examines an unstable, assaulted femininity in Repulsion, immediately proving her considerable range in the shocking contrast between both roles. Carol’s aloofness towards aspiring suitors in public hides the disgust that comes out more openly at home, specifically towards the boyfriend of her older sister, Helen. Even his habit of leaving his toothbrush in the same cup as hers invokes uneasy frustration, its placement taking on psychosexual significance as a figurative penetration, and the smell of his dirty clothes is enough to make her throw up. When she is left home alone for weeks without the company of another woman though, her obsessive paranoia expands uncontrollably in manic directions.

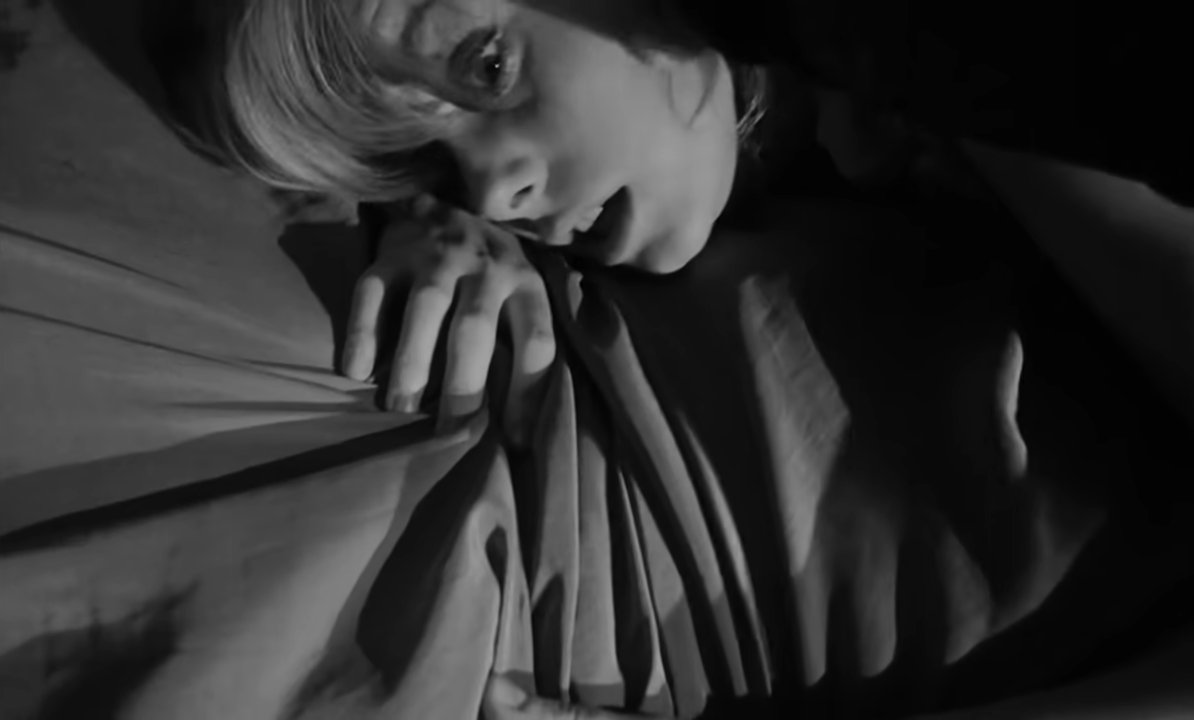

Deneuve’s performance is certainly helped as well by Polanski’s natural penchant for close-ups, isolating her disturbed reactions to the sound of Helen having sex in another room, and fragmenting her face with obstructions and shadows. This skilful framing of actors’ expressions is of course drawn directly from Ingmar Bergman’s playbook, though Polanski clearly favours it as a device to craft suspense and terror over subdued drama. Wide-angle lenses uncomfortably press us up against Deneuve’s face, invading her personal space within claustrophobic rooms, while the reflective surfaces of elevator mirrors and kettles create distorted, unsettling doubles in the mise-en-scene. Save for the epilogue which takes a step back into reality, Polanski hangs his subjective camera entirely on Deneuve and her erratic perspective, arousing an eerie discomfort from her vacant, wide-eyed gaze.

Quite crucially, the array of symbolic motifs that Polanski formally organises around this tortured woman gives sinister shape to her breakdown, keeping Repulsion from falling into meaningless chaos. If Carol’s apartment is an embodiment of the afflicted mind she is trapped inside, growing more shambolic with overflowing bathwater and rotting carcasses, then the fracturing walls that she hallucinates suggest a similar splintering of her psyche’s very foundations. The cracked pavement that inexplicably captures her attention long before this is one of many seemingly insignificant visual cues here that plants a seed in her mind early on and later flourishes as a monstrous expression of primal horror, though the most horrific instance of this doesn’t arrive until the landlord’s fatal visit.

Leading up to this point, Carol has been tormented by dreams of men breaking into her bedroom and viciously raping her, viscerally captured by Polanski’s handheld camera and set to nothing but the muted sound of a ticking clock. The first murder she commits out of extreme paranoia toward her unwanted suitor Colin seems to come as a direct result of those hallucinations, but when the landlord visits to collect rent money, attempts to take advantage of her, and brings her nightmare to life, we are given good reason to sympathise with her violent reaction. It is important to note that the razor she wields against him is in fact Michael’s, and thus she adopts its masculine power as she turns the tables on her attacker and slices him to death.

Not that this surge of retributive justice brings Carol any relief, or even an end to her rape dreams. If anything, her descent into madness only escalates from here, as she delusionally irons her clothes without power and lets the apartment sink into filthy disrepair. Where Polanski initially composes his oppressive shots in Repulsion with an Antonioni-like framing of interior architecture, his visuals evolve here into a surreal bombardment of avant-garde stylings, leading Carol down a corridor of protruding hands that forcefully grope at her body.

If we are to single out a visual motif that unlocks the key to Carol’s deepest trauma though, then we must look to the very final shot of Repulsion once Helen and Michael have returned from vacation, discovered the gruesome remnants of Carol’s murderous breakdown, and found her in a catatonic state. While panicked family and neighbours scramble to help, Polanski’s camera tracks in on the family photograph that our gaze has been drawn to multiple times throughout the film, and yet which only now reveals an insidious secret. Partially obscured by the surrounding mess, only two faces are now visible – that of an older male family member with a wide grin, and of a young girl staring at him with profound loathing. At the core of Polanski’s surreal, psychological horror, there is simply a wounded woman forced into a depraved repression, miserably trying to contain its resulting damage to her mind, home, and whatever men dare to cross the threshold into either.

Repulsion is available to purchase on Amazon.

Pingback: An Inexhaustive Catalogue of Auteur Trilogies – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Female Performances of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Female Actors of All Time – Scene by Green