Michelangelo Antonioni | 1hr 57min

Ever since young mother Giuliana was caught in a car collision that left her with lingering trauma, the world hasn’t seemed quite right. The industrial Italian town where she lives with her husband Ugo and son is an inhuman landscape of bizarre, alien structures, twisting steel beams and pipes around engines that never seem to stop churning, and chimneys that spit out blasts of fire. There is nothing vaguely hospitable about the harsh angles they impose on their environment, and neither is there any warmth to be found in strange beeps and clangs that constantly echo through polluted open spaces.

Still, under Michelangelo Antonioni’s dreamy direction we are left to question – how much of Red Desert is simply the perception of an unstable psyche, and how much is the real degradation of modern society? It is often difficult to discern where the cold, metallic sound design ends and where the synthesised score begins, ringing electronic wavelengths through the atmosphere to maddening effect. Few others who live here seem as disturbed by the ravaging of nature as Giuliana, who wanders its greasy factories and contaminated estuaries in a state of lonely discontent. She desperately desires the company of others, but even more than that she yearns for them to protect her from the sickness of the world, blocking it out like a barrier of empathy rather than steel or cement.

“I don’t know myself. I never get enough. Why must I always need other people? I must be an idiot. That’s why I can’t seem to manage. You know what I’d like? I’d like everyone who’s ever cared about me… here around me now, like a wall.”

For now though, all that surrounds Giuliana is the industrial “architecture of anxiety” as critic Andrew Sarris labels it, physically dominating her slight frame at every angle. Red Desert is visually distinct from Antonioni’s previous works as his first film shot in colour, but it is also very much a thematic continuation of his ‘Alienation’ trilogy, using the shapes and patterns of modern infrastructure to lose his characters in confusing, inhospitable environments. Rather than islands or cities though, Red Desert is primarily shot on location around the petrochemical plants and rustic docks of rural Italy, uncovering an awe-inspiring beauty in those manufactured structures that were not designed with aesthetics in mind. Instead, it is the purely functionality of these formations that Antonioni relishes, framing their spatial symmetries, parallel lines, and geometric configurations with rigorous precision in his astounding long shots, and carefully blocking his tiny human subjects among them.

Not content with limiting himself to the landscape’s natural colours though, Antonioni pushes his visuals even further with tints of vibrant artifice that break through the monotonous, desaturated greys. Proclaiming his desire to “paint the film as one paints the canvas,” the Italian filmmaker took to his mise-en-scène with literal cans of paint, subtly accentuating the scenery’s neutral tones while aggressively splashing lively reds across the frame.

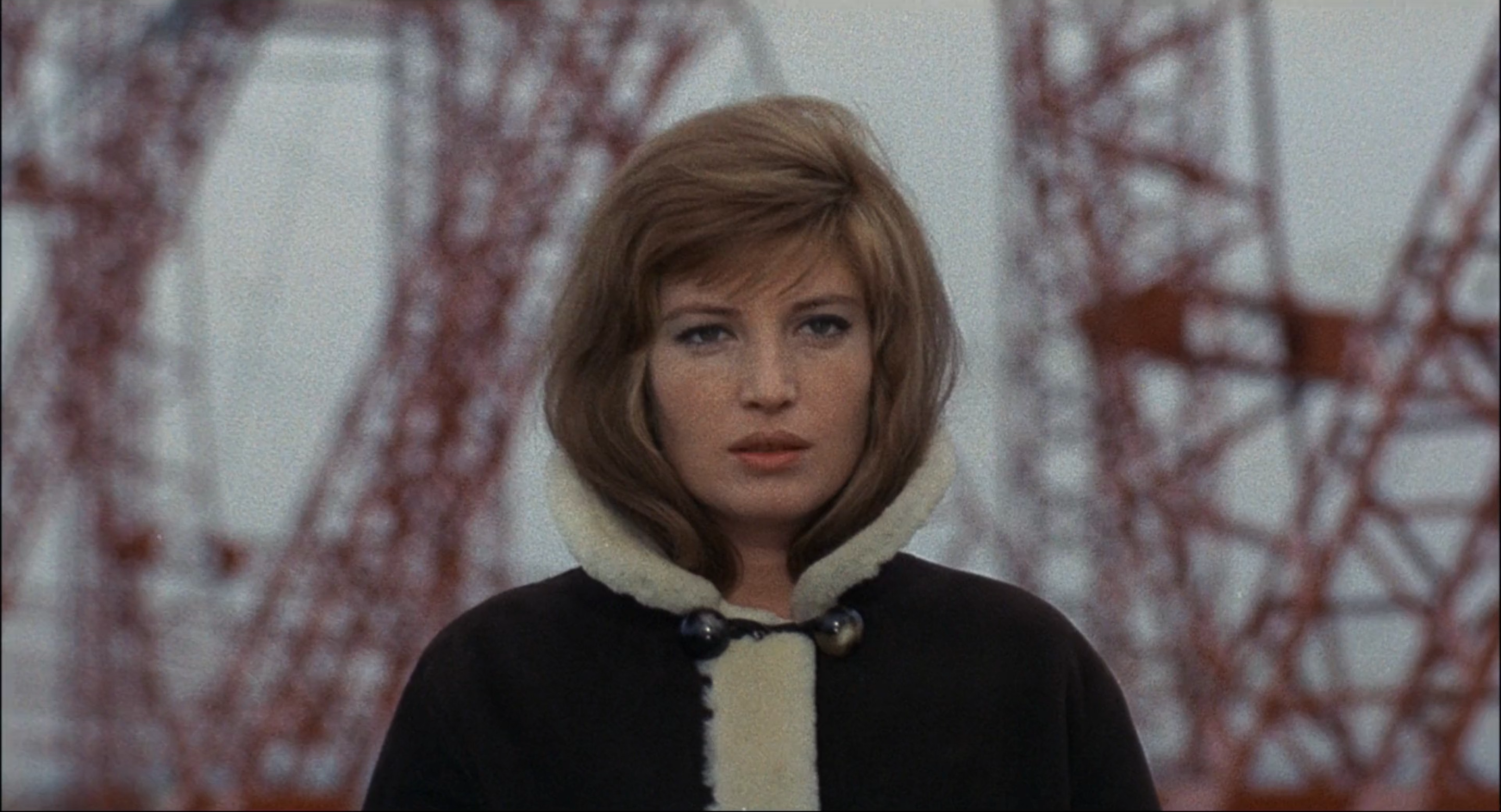

The strongest use of this palette comes in the radio telescope set piece, stretching an enormous length of crimson scaffolding far into the distance while workers climb its triangular trusses. Given its alien appearance, the structure’s purpose is not immediately obvious, though the explanation that it allows humans to “listen to the stars” makes sense. This is a culture with its eyes turned upwards rather than inwards, paying far more attention to the undiscovered ceiling of human progress than the quality of day-to-day living. While impressive leaps are made in astronomy and energy technologies, the Earth and its inhabitants waste away in silence, struck by physical and psychological illnesses that all originate from the same place.

As a result, the settings that Antonioni captures in Red Desert often border on apocalyptic. Piles of corroded debris obstruct shots of Giuliana’s aimless roaming in junkyards, and a brief retreat into a riverside shack with friends offers only temporary respite from the dense fog gathering outside. Antonioni’s blocking of bodies remains impressive even in medium shots here, tangling them around each other in lounging positions that look none too comfortable, and continuing to weave in his red palette through the tarnished wooden walls.

The moment a ship carrying diseased passengers drifts into shot through a window though, the brief comfort that Giuliana that found here immediately dissipates, and she reverts to the hysterical state that her nightmares have often brought on. Not only did she attempt suicide shortly after her car accident, but her following experience being hospitalised left her with a harrowing fear of “Streets, factories, colours, people,” and of course any illness that might once again render her helpless. The silhouetted figures of her friends staggered through the mist outside are more ominous than they are comforting under these circumstances, agitating her to the point that she tries to escape in a panic and nearly drives off the end of the wharf. The visual metaphor that Antonioni composes here of Giuliana’s car ready to tip over the edge of the world is devastatingly bleak, with the tall, unlit beacon tower diminishing her presence and the grey negative space eerily beckoning her into the void.

When Antonioni isn’t trapping Giuliana within wide open expanses and behind architectural obstructions, it is his shallow focus which softly detaches her from these surroundings, envisioning her subconscious defence mechanism. It is an unusual device for a filmmaker so attached to his crisp depth of field, and yet its formal introduction in the out-of-focus opening credits and emphasis on Monica Vitti’s subtly expressive face in close-ups is wielded with exceptional care, isolating her marvellous performance against red, liquefied backdrops. She is filled with an aching hunger to simply connect with another being, and yet the more she reaches out, the more lost she becomes. When she finally makes love to a man, Antonioni’s disjointed editing keeps their passion at a cold distance, and her attempt to communicate with a German sailor by the dockyard is painfully hindered by the language barrier between them.

Unfortunately, the emotion that Vitti pours into this role is not always reciprocated by Richard Harris as Corrado, her husband’s business associate and the one man she connects with on a personal level. Neither does the magical realist bedtime story interlude that whisks us away to a distant island paradise formally integrate so well with the rest of Red Desert’s grim naturalism. Still, Antonioni’s stark cinematic ambition cannot ultimately be overshadowed by these flaws as he works his obsession with rich pigments into Vitti’s capricious character.

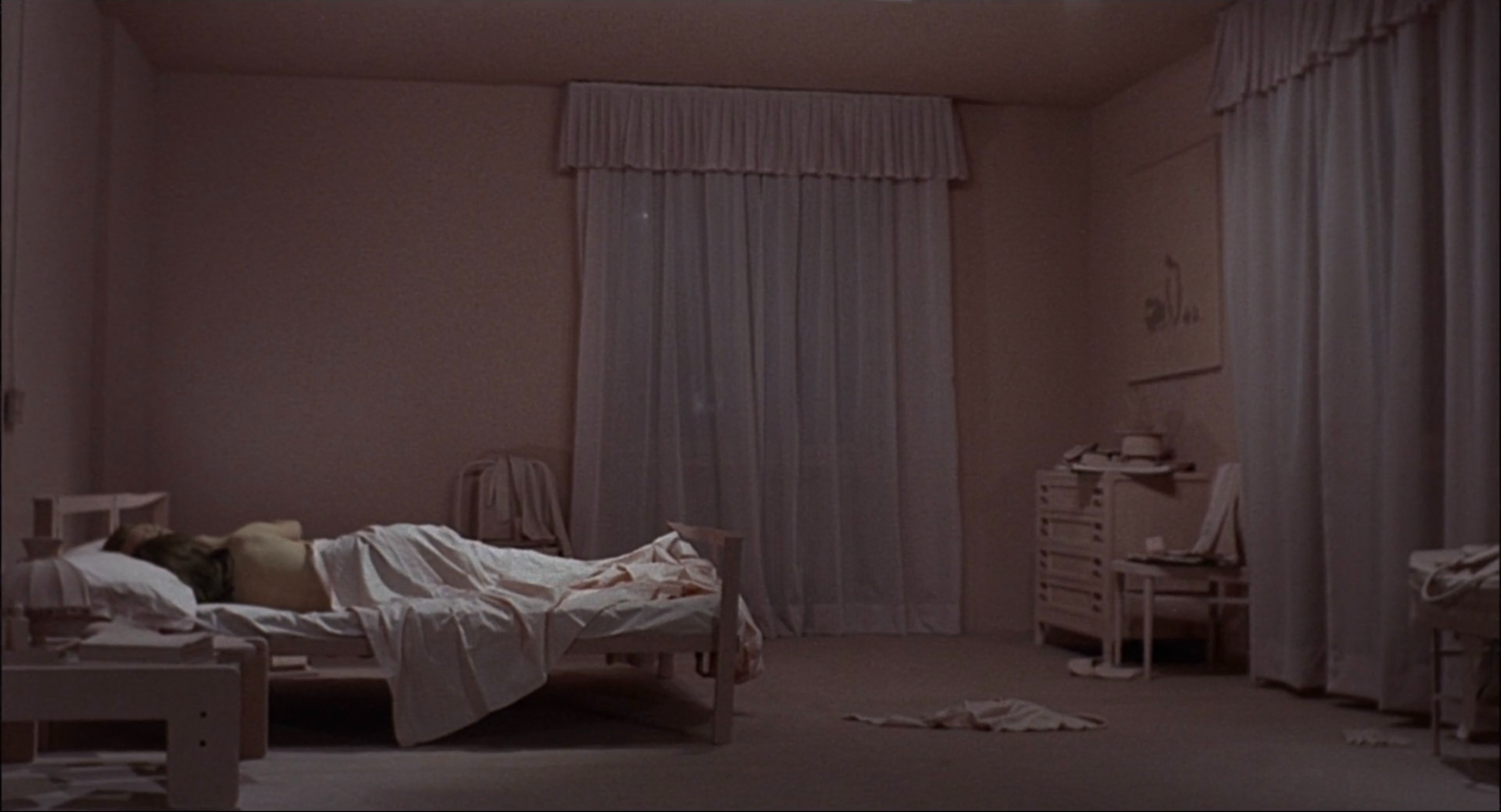

Though she erratically claims to be scared of colour, she also dreams of filling her unopened ceramics shop with it, opting for light blues and greens in a subconscious reaction against the angry red steel of her outside environment. Whether it is the pink walls of her bedroom of the green décor of Corrado’s tidy living room, Antonioni often uses the soft palettes of his interiors to offset the vibrancy of his landscapes, though visually these amount to little against the sheer mass of the world’s barren greyness.

If our humanity is to break through at all, it is not in acts of individual expression, but the giant displays of human industry mounted on arid plains, spewing yellow smoke into the dirty air. Passing birds know not to fly there, Giuliana poignantly explains to her son, though it is a sad state of affairs to begin with that such innocent creatures must be taught to navigate manmade danger in a world that no longer has a place for them. At this point, there are no easy solutions to reverse society’s reckless pursuit of progress and profit, Antonioni realises. To live is to merely survive, and yet in though slow deterioration of Red Desert’s earth, air, and water, even that is dangerously at risk.

Red Desert is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and the DVD or Blu-ray are available to purchase on Amazon.

I thought Richard Harris was decent here. Nice to see him in a younger role. But the dubbing of him is not great.

With some retrospect I think it’s mostly that he’s a bit forgettable and doesn’t make a huge impact – though admittedly that would be a tough task next to Monica Vitti.

Pingback: The 100 Best Female Performances of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Female Actors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Film Editors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Shot Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Cinematographers of All Time – Scene by Green