Jean Cocteau | 1hr 36min

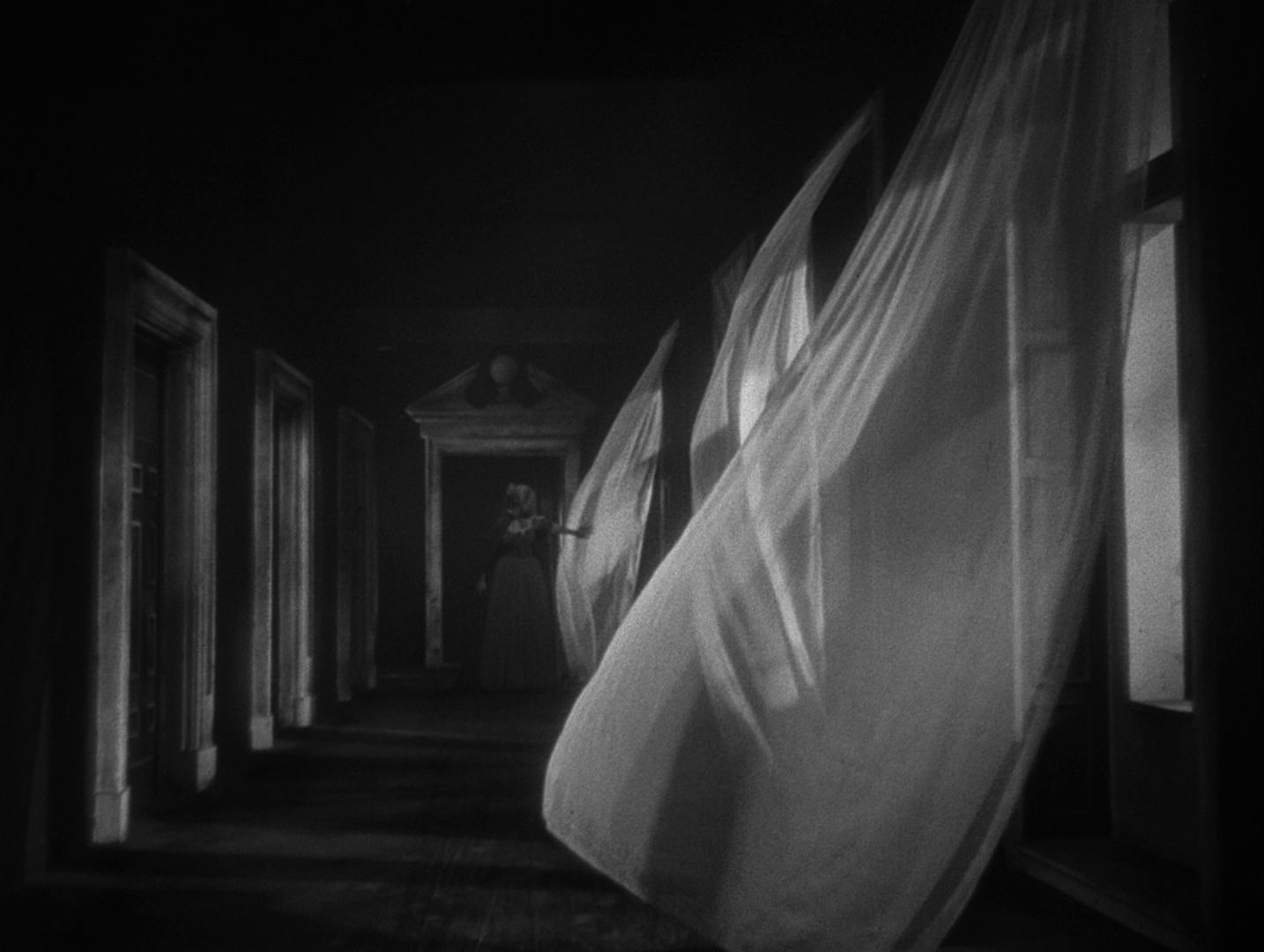

It is not just the fantastical designs and living furniture which imbue the enchanted castle of Jean Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast with an air of otherworldly awe. Time inside this ethereal realm mystically warps in unexpected directions, stretching out in delicate slow-motion when the captive Belle runs down hallways of billowing white curtains, and flipping it around with reverse photography as a collection of loose pearls magically form a necklace. Given that its days and nights are completely out of sync with the village situated just a few miles away, it might as well exist in its own time zone too, consumed in darkness when the sun should be shining.

As a skilled technician of practical effects, Cocteau is fully dedicating his illusory craft to our complete disorientation, further manipulating our own suspended disbelief as spatial dimensions disappear altogether in feats of teleportation and clairvoyance. The Beast’s castle defies logic in more ways than just its eccentric mise-en-scène. The very system of logic it operates on exists entirely outside of our own, making for a world that is as inventively surreal as it is fearsome.

Especially in contrast to Disney’s animated adaptation of the French fairy tale, Cocteau’s vision possesses a far more whimsical horror. When Belle’s father first enters the Beast’s domain after getting lost in the forest, he is welcome by arms protruding from stone walls and holding candelabras to light his way, while faces carved into the dining hall’s ornate fireplace quietly observe his movements. These are not humans transformed into objects, but rather embodiments of the castle’s own sentience, opening doors and whispering to its inhabitants as if possessed by ghosts.

Where Georges Auric’s fabulously lush orchestrations build to grand crescendos outside this estate, the addition of a haunting choir within its dark chambers gives the eerie setting its own non-diegetic voice, effectively breathing life into that which is inanimate. Cocteau’s curious camera underscores the mystery even further too as it moves in dangerous anticipation of what we might find at the end of long corridors, while the cluttered Gothic décor obscures our clear view of what lies submerged in dark voids of negative space.

From the doorways encased in ornamental carvings to the grand stone sculptures guarding the castle walls, Beauty and the Beast is a towering landmark of cinematic production design, constructing an architectural marvel as phantasmagorical as its cursed master. The Beast’s anthropomorphic design is beautifully detailed, marking an incredible accomplishment of prosthetic makeup in his realistic fur and fangs, while possessing a low, raspy voice and human eyes which reveal a deep sorrow. It isn’t just that he is ugly, but this Beast also confesses that he is hopelessly dim-witted, and feels that this dehumanises him in Belle’s eyes. “You stroke me like you stroke an animal,” he laments, though it is her thoughtless response that stings even more.

“But you are an animal.”

To further underscore his monstrosity, the curse which was placed on him as a child also causes his hands to smoke whenever he is driven by his primal instinct to slaughter a forest creature, betraying his barbarity and driving him deeper into shame around his civilised guest. Though this version of Beauty and the Beast is far more faithful to the classic fable than Disney, these small, cinematic inventions shape it into its own fantastical character study, examining the thin line that separates virtuous honour from depravity.

The dual casting of Jean Marais as both the Beast and Belle’s vain suitor Avenant works brilliantly in this formal comparison too, especially as the Beast eventually finds himself becoming human, and Avenant respectively takes on his hideous form. “Love can turn a man into a beast. But love can also make an ugly man handsome,” the newly transformed Prince poetically expounds, before lifting into the air with Belle in a sudden gust of smoke and wind.

Beyond this anti-hero and villain, Cocteau continues to lay out humanity’s shortcomings in Belle’s jealous sisters who manipulate her into turning down a more prosperous life, as well as her brother Ludovic who decides to help Avenant kill the Beast. Even Belle herself is forced to come to terms with her own selfishness when she realises her actions have led to the Beast’s impending demise, kneeling over his ailing body by a stream and tearfully confessing “I am the monster!”.

Indeed, moral virtue and corruption exist within each character to varying extents, though it is only through the filter of twisted dreamscapes that this sort of nuance becomes visible, allowing us to penetrate their deceptive facades of beauty and ugliness. Just as worlds of the conscious and subconscious collide in the love shared between Belle and the Beast, Cocteau also reconciles contradictions of the body and spirit with poetic justice, embracing a wishful ending that he recognises with whimsical poignancy may only ever exist in the boundless, imaginative possibilities of fairy tales.

Beauty and the Beast is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and the DVD is available to purchase on Amazon.