Cord Jefferson | 1hr 57min

The point of no-return for novelist Monk Ellison has long passed by the time he winds up on a literary judging panel trying to expose the stupidity of his own anonymous parody book. The idea for ‘Fuck’ struck one night after a string of frustrating experiences with white publishers looking for a more racial perspective in his writing, as well as those Black authors who cater to their expectations, and so the sudden influx of serious critical praise towards his novel is equal parts revealing and frustrating.

Complicating matters even further is the character he has invented for his pseudonym Stagg R. Leigh, an offensively crude ex-convict on the run from the police who has since become widely celebrated in the public eye. Meanwhile, Monk and his intellectual, non-racial novels continue to fly under the radar – and so when he finds himself on that panel listening to his fellow judges exalt ‘Fuck’ as a raw, honest piece of African American literature, Cord Jefferson does not pass up the chance to deconstruct the uncomfortable absurdity of the entire situation.

With this social criticism set as its base argument, American Fiction’s sharp-edged screenplay continues to wield an impressive self-awareness of its own premise, satirising the liberal elite and their attempts to assuage their white guilt by gleefully consuming what Monk calls “Black trauma porn.” When Monk finally gets a chance to sit down with the only other African American judge on this literary panel, Sintara Golden, our expectations have been thoroughly set him up to tear apart her wildly successful and indulgently racial book ‘We’s Lives in Da Ghetto,’ and yet what follows unexpectedly turns a mirror back on our own smug cynicism.

The first subversion of the scene comes when Sintara agrees with Monk that ‘Fuck’ is inauthentically pandering – “The kind of book that critics call important and necessary but not well-written.” His relief to finally hear a voice of reason leads to confusion when he asks how she can then persist in her career of frivolously humouring white audiences, to which her manner suddenly hardens. Much of her writing was drawn directly from interview transcripts and comes from hours of research, she tells him. Besides, he hasn’t even read her book, and she’s not to blame if readers happen to form stereotypes from genuine artistic expression. What justification does he have to criticise the hard work of others and accuse them of phoniness, simply because he has never shared their experiences?

The biting punchline to the entire affair comes shortly after when the rest of the panellists reconvene to finally decide the winner of the literary prize, and it is no surprise that Monk and Sintara’s opinions are passed over in favour of the white majority who adore ‘Fuck.’ Of course, in a moment of self-congratulatory praise, one of the white judges can’t help but miss the irony of the entire farce either.

“It’s not just that it’s so affecting. I just think it’s essential to listen to Black voices right now.”

The balancing act of comedy and drama that Jefferson pulls off all through American Fiction is expertly executed, though the contribution of Jeffrey Wright’s performance to this symmetry should not be overlooked. As valid as Monk’s point is about the state of racial sensitivity in America’s creative arts industry, his own intellectual arrogance frequently seeps through, distancing even his new girlfriend Coraline when she admits to liking ‘Fuck’ without realising he wrote it.

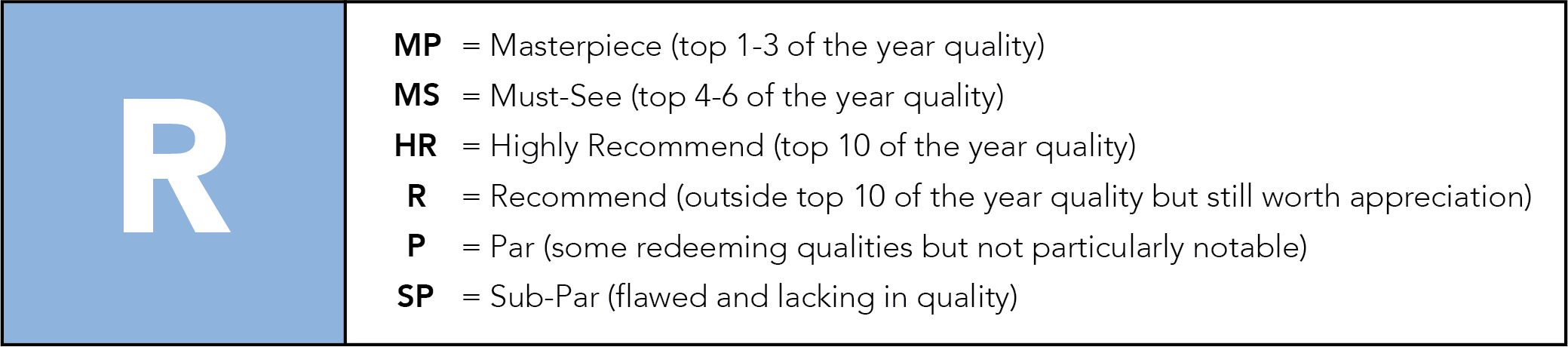

This second narrative thread that revolves around Monk’s romantic and family life draws that line down the middle of the film even further, but most importantly Jefferson also cleverly uses it as a self-aware response to its other, more satirical half. As Monk navigates complications around his sister’s sudden passing, his brother’s wild lifestyle, and his mother’s degenerative dementia, Jefferson reveals dimensions to his life that only ever tangentially interact with his race.

Not that the readers who fawn over ‘Fuck’ would ever appreciate such personal, non-race related stories, should he ever choose to weave them into his fiction. Monk is a difficult man who is familiar with many different types of grief and often falls to his own hubris, and yet for the sake of American consumers these complex characteristics must be flattened into a single identity apparently shared by all people of his colour. American Fiction’s metafictional epilogue only serves to underscore the artificial manipulation of these voices by executives, filtering itself through different genre lenses until it too submits with comical self-awareness to a marketable tragedy, not unlike the inverted, faux-happy ending of Robert Altman’s The Player. Even as Jefferson levels critiques at the publishers, critics, and audiences who twist his artistic expression to their liking, he realises that their naïvely simplistic takes are inescapable, ultimately submitting American Fiction itself to the very subject of its cleverly inspired interrogations before anyone else can get there first.

American Fiction is currently streaming on Amazon Prime Video.

Pingback: The Best Films of 2023 – Scene by Green