Aki Kaurismäki | 1hr 21min

In a cheap Helsinki supermarket, shelf stacker Ansa is let go for stealing expired food to supplement her meagre pay. Not too far away in the same city, depressed labourer Holappa is fired for drinking on the job, and booted from the shipping container dormitory that he shares with his blue-collar coworkers. There is no melodrama or heightened emotion surrounding these narrative beats in Fallen Leaves. They are facts of life, as fixed and unchangeable as those radio reports tracking Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which constantly cast their relatively low-stakes problems against a backdrop of largescale warfare.

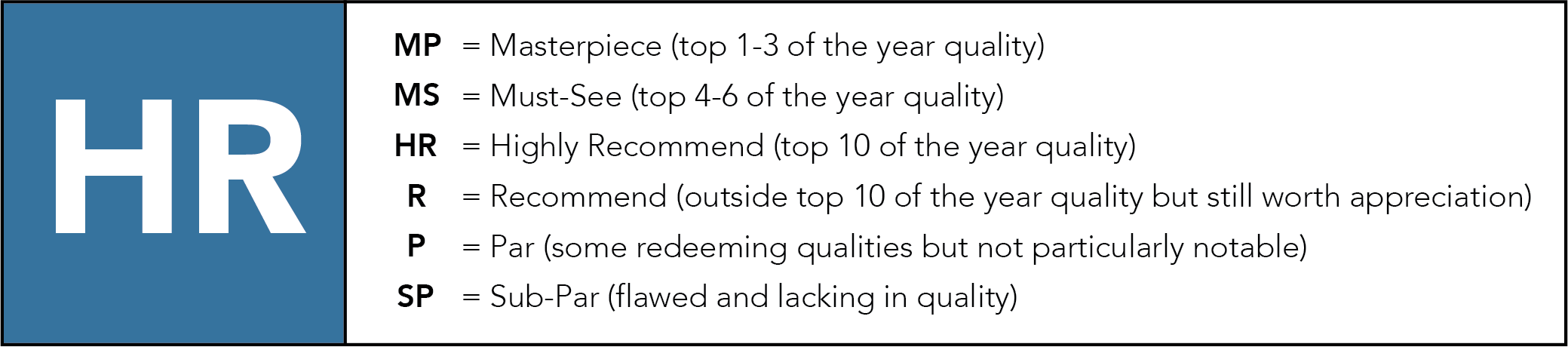

Still, Aki Kaurismäki remains sympathetic to those whose struggles are not notable enough to be broadcast internationally. The sickness that suffocates Ukraine similarly seeps over the Russian border into Finland, gripping its people in a constant state of unease with endless stories of death and destruction. The formal rigour of this news report motif is undeniable, using sheer repetition to grind us down into the same weary resignation that these characters have long inhabited, while occasionally breaking the dourness with beats of Kaurismäki’s trademark deadpan. When Ansa turns the radio on to set a romantic mood during her first proper date with Holappa, the grim Ukraine report that she tunes into instead makes for a darkly funny punchline, paying off on a long setup of news announcements begging to find some light in the mundane gloom.

This is the glimmer of hope that Kaurismäki keeps alive throughout Fallen Leaves, despite the many good reasons these lovers are given to disregard it. At first, it is shyness that maintains a distance between Ansa and Holappa at the karaoke bar where their friends strike up conversation, leaving them to simply make eye contact across the room. Their second encounter at a tram stop where Holappa has passed out is only tangential, only seeing him wake up a few seconds after Ansa has boarded, and from there fate continues to make an enemy of their potential romance.

When Ansa and Holappa finally do make it to a first date, an ill-timed gust of wind blows her phone number out of his hand and delays their reconnection, though Kaurismäki is not one to let them off so lightly without any blame either. Holappa’s alcoholism can take full credit for their eventual breakup, yet this also in turn spurs him to conquer his addiction. Even as bad luck and personal flaws continue to rear their head, perseverance keeps love alive, forging unlikely bonds in a world where random misfortune is the only escape from soul-crushing tedium.

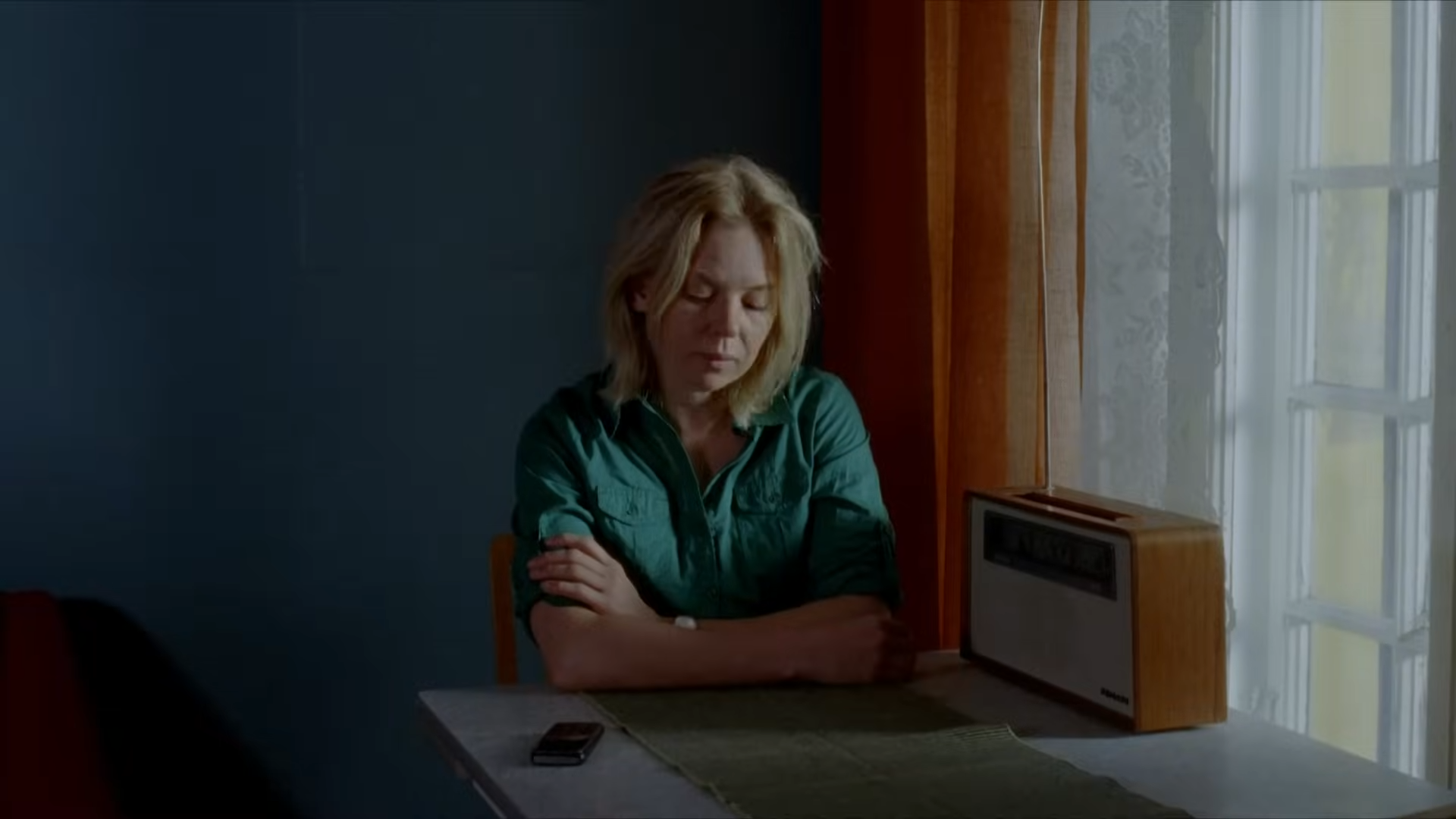

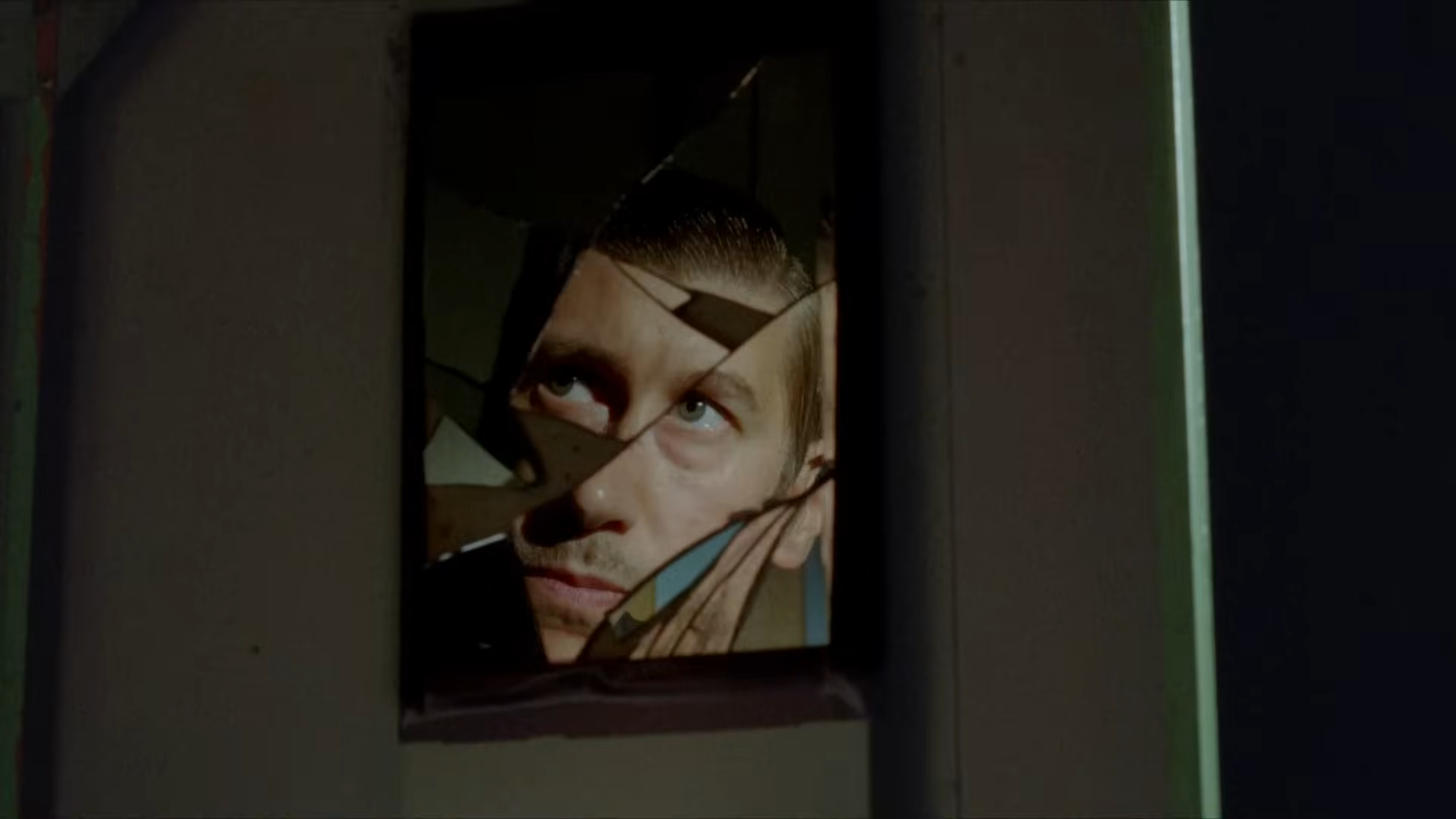

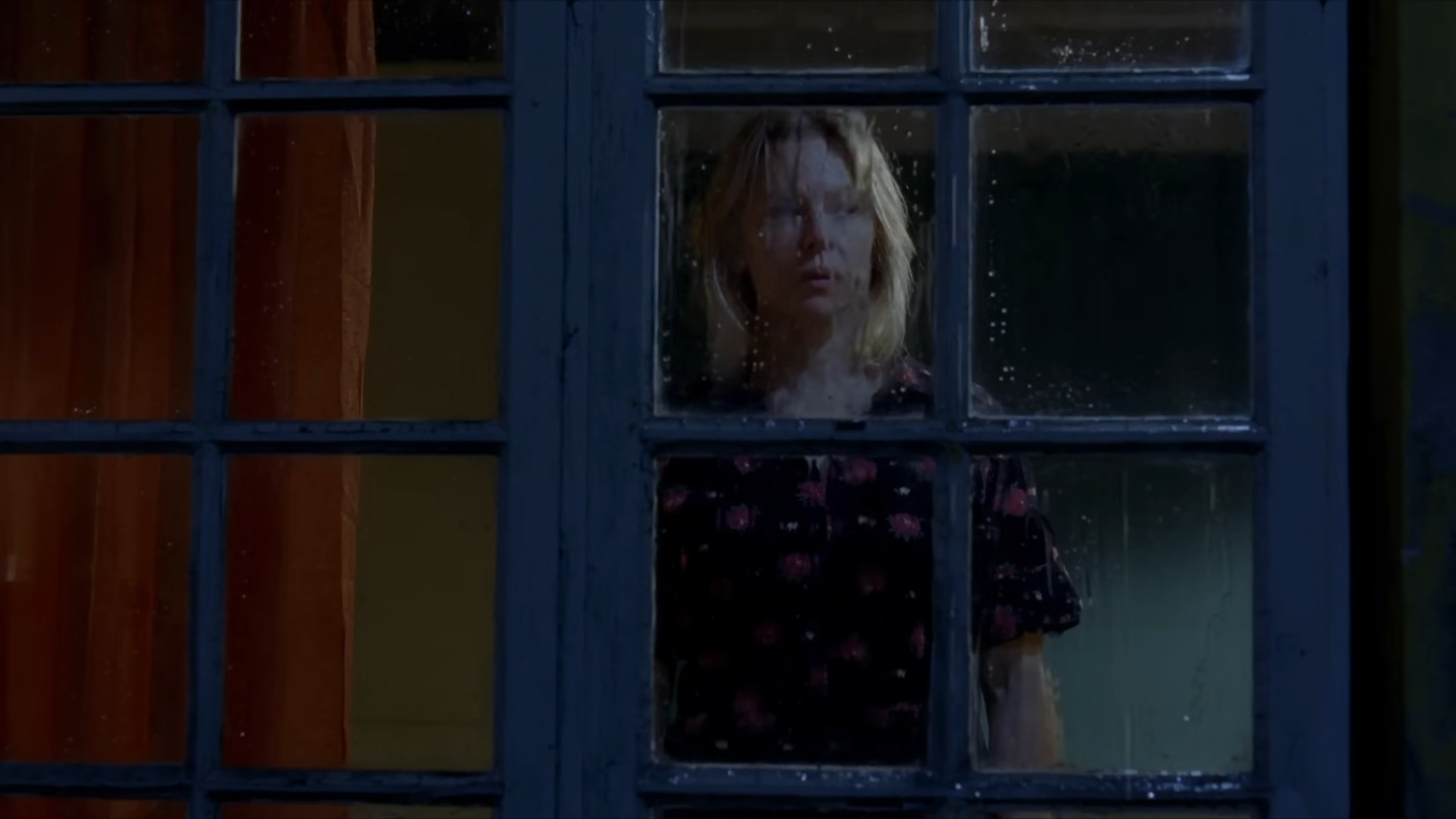

Visually, this optimism frequently manifests as vibrant interior décor decorated with bold primary colours, like a Rainer Werner Fassbinder melodrama minus the expressive performances. Kaurismäki lets his framing speak for his characters where they are otherwise incapable, in one instance shooting Holappa with a yellow shirt and Ansa with a red blouse on either side of a dinner table, and then uniting their respective colours through an arrangement of flowers in the middle. Conversely, the distance between them is emphasised when they sit on either side of a red couch in awkward silence, imprinted against the blue wall of Ansa’s apartment.

Quite significantly, the image of modern-day Finland that Kaurismäki constructs around these lovers is also one that is strained by a lingering Communist influence from the nation’s most powerful neighbour, imbuing Fallen Leaves’ setting with a timeless, retro quality. Though set in 2024, Ansa and Holappa are entwined in a mesh of eras – radios haven’t quite been replaced with televisions yet, mobile phones are notably primitive, and the movie posters that decorate theatres and bars advertise the 1960s works of Godard, Visconti, and Bresson.

When our protagonists do finally enter a cinema, the screening of The Dead Don’t Die is notably out-of-place in Fallen Leaves as one of the few modern movie references, and yet it also falls in line with Kaurismäki’s admiration for the deadpan comedy of Jim Jarmusch. Not only is The Dead Don’t Die an odd choice as a lesser film in Jarmusch’s career, but the absurd comparison drawn by two other cinemagoers to Diary of a Country Priest and Bande à Part underscores the scene’s offbeat incongruency even further, with Ansa’s straight-faced review that she’s “never laughed so much” completing the hilariously ironic sentiment.

None of this dissonance is without purpose in Kaurismäki’s rigidly minimalist world though, locating Ansa and Holappa in a culture that cannot quite figure out its own identity. It is no wonder that every interaction in Fallen Leaves is so burdened with awkward uncertainty, moving conversations forward at a cumbersome pace. When pressed as to why he drinks, Holappa explains it is because he is depressed, and when asked why he is depressed, he links it back to his drinking. Circular reasoning leads to loops of self-degradation in these characters’ lonely lives, and so when Ansa realises that Holappa isn’t ready to break out of the miasma with her, she seeks comfort in the innocence of a stray, abandoned dog.

These lovers may be set back by their own flaws, but the greater cosmic joke being played on them can’t be ignored, testing their willingness to fight for a sincere, patient love. That Ansa and Holappa both remain totally unaware of each other’s names right to the romantic, Chaplinesque end of Fallen Leaves speaks eloquently to their incredible will and intuition, rejecting their lonely destinies seemingly written out for them and fighting for their right to happiness. When the potential for authentic, selfless love is discovered in a world as unpredictably offbeat as Kaurismäki’s, the power to nourish it lies solely with those at its centre, stubbornly overcoming whatever fated obstacles may seek to challenge their most basic human need.

Fallen Leaves is currently playing in theatres.

Pingback: The Best Films of 2023 – Scene by Green