Todd Haynes | 1hr 53min

There is always something authentically human lost in performative imitations of reality, and no matter how much actress Elizabeth Berry tries to capture it in her twisted attempts at method acting, that missing element continues to elude her. The subject of her research in May December is former schoolteacher Gracie, who was caught twenty-three years ago sleeping with her student Joe and was consequently sentenced to prison. The fact that they have since gotten married and raised three children together does little to quell the nauseating discomfort of her manipulation, but if Elizabeth is to deliver an accurate portrayal of Gracie for her upcoming movie, then such judgements must be put aside.

Not that the creative results are necessarily worth the pain inflicted. In Todd Haynes’ eyes, both the art and the humanity it imitates are drained of their dignity, tragicomically warping the suffering of Gracie’s abused husband into superficial imagery. Even at Elizabeth’s subtlest, her shadowing of Gracie’s everyday movements is entirely intrusive, offering insights that she later records as voice memos describing her subject’s visual features and odd mannerisms. When she runs a Q&A at a local high school drama class, she explains her acting process that compels her to study humanity’s darkness and spontaneously give into its organic rhythms, though it isn’t until we see this in action that we truly appreciate the emptiness of her endeavour.

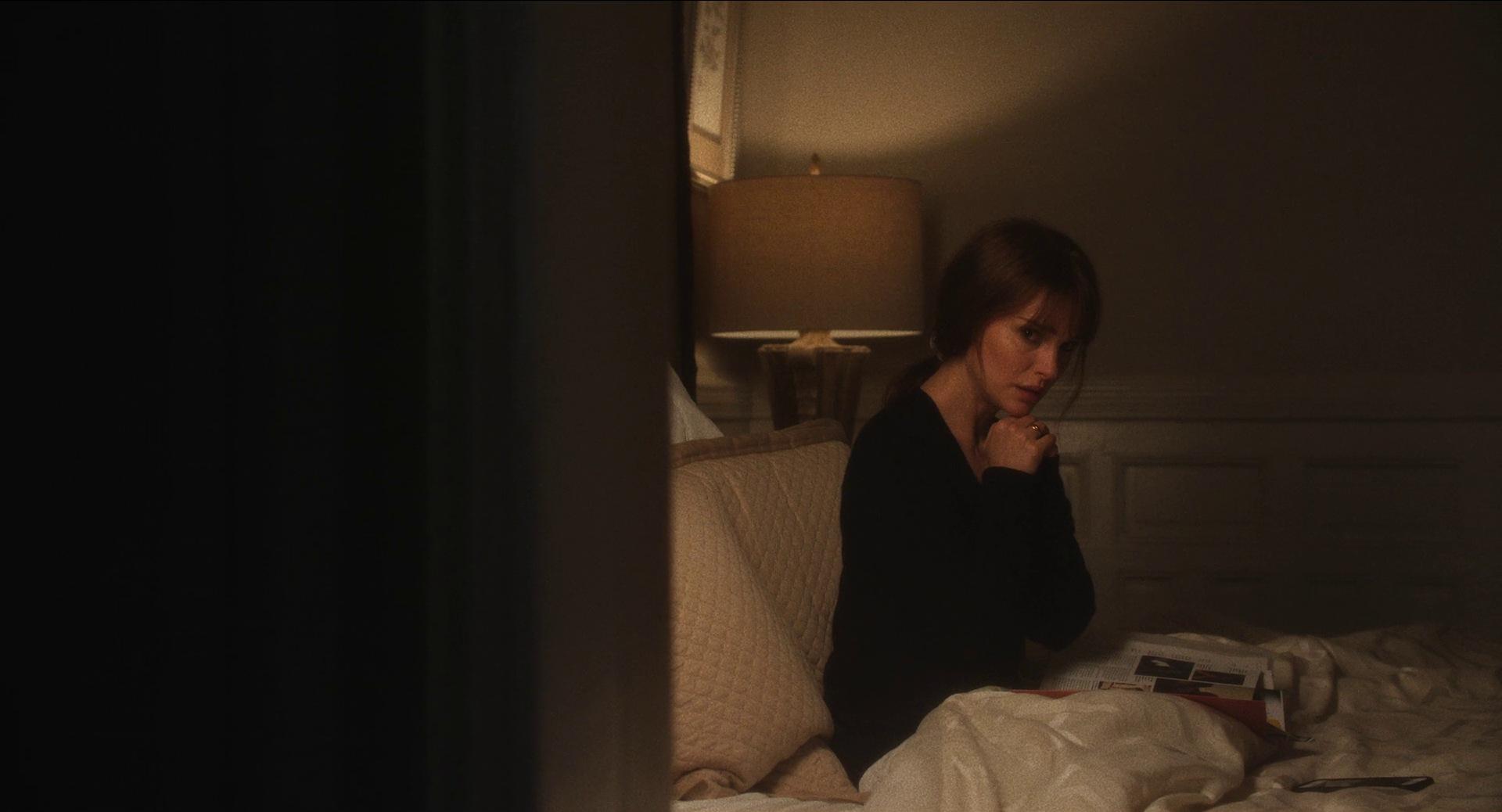

It is especially in the pet shop storeroom where Gracie was first caught with Joe that Elizabeth finds herself overcome with that passion. As she leans back against the wall, she begins to pleasure herself, while Haynes silhouettes her in a dim blue light and slowly zooms his inquisitive camera in on her shallow re-enactment. For the sake of her own full-bodied immersion, some degradation of Gracie and Joe’s lived experience is required, crossing the line of good taste so that it may be offered up for mass consumption in cinemas and living rooms.

Later, this blurring of identities extends to an illicit affair between Elizabeth and Joe, though one which she claims no personal investment in. His heartbreak is made all the more tragic by his gradual recognition of the innocence he lost to Gracie, and his desperate attempt to find a real connection with a woman his own age. When he asks Elizabeth what their intimacy actually means to her, her response is chillingly condescending, with Natalie Portman’s deadpan line delivery reinforcing the same blasé attitude that Gracie used to justify her paedophilic molestation twenty-three years ago.

“This is just what grownups do.”

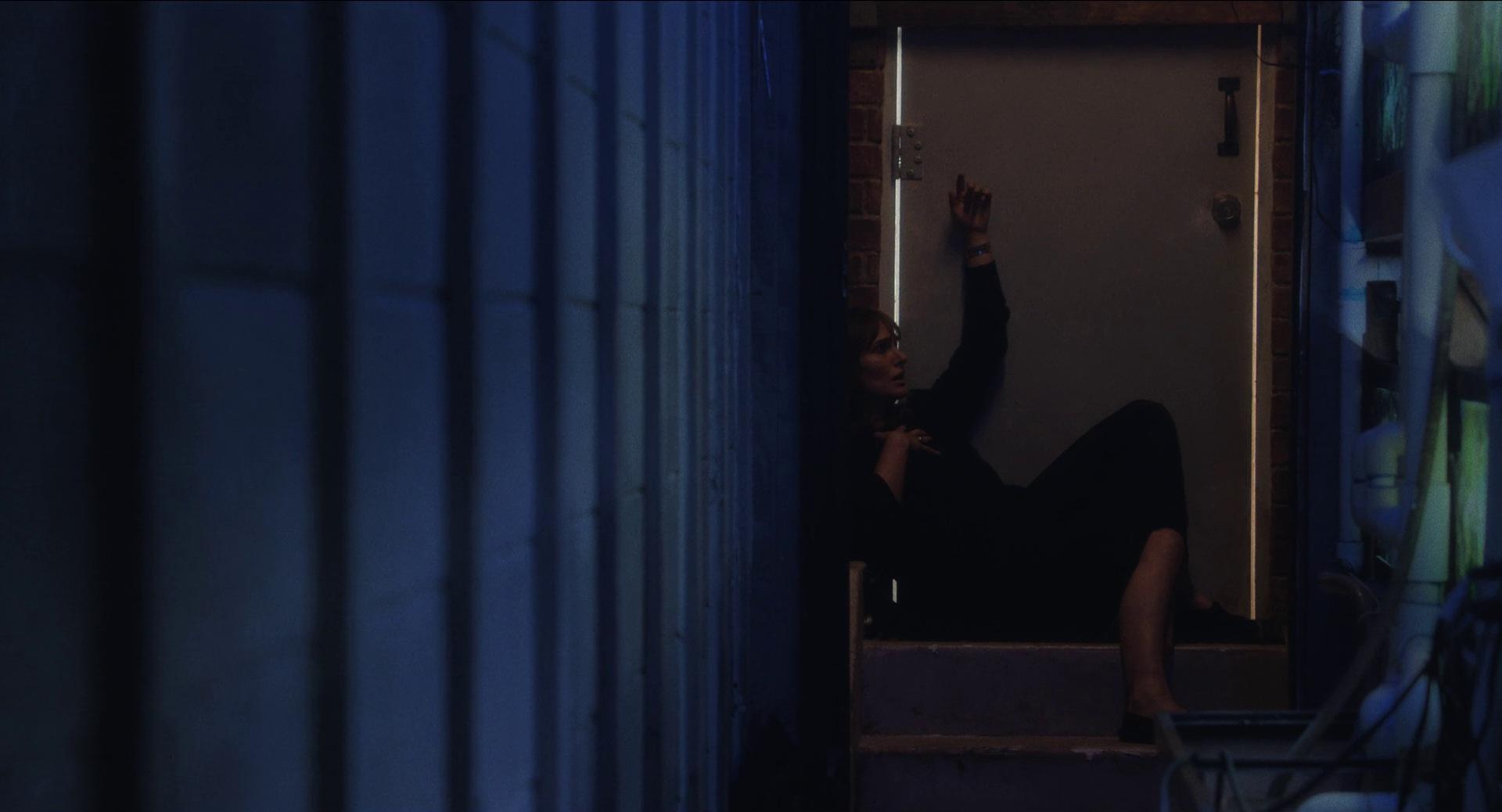

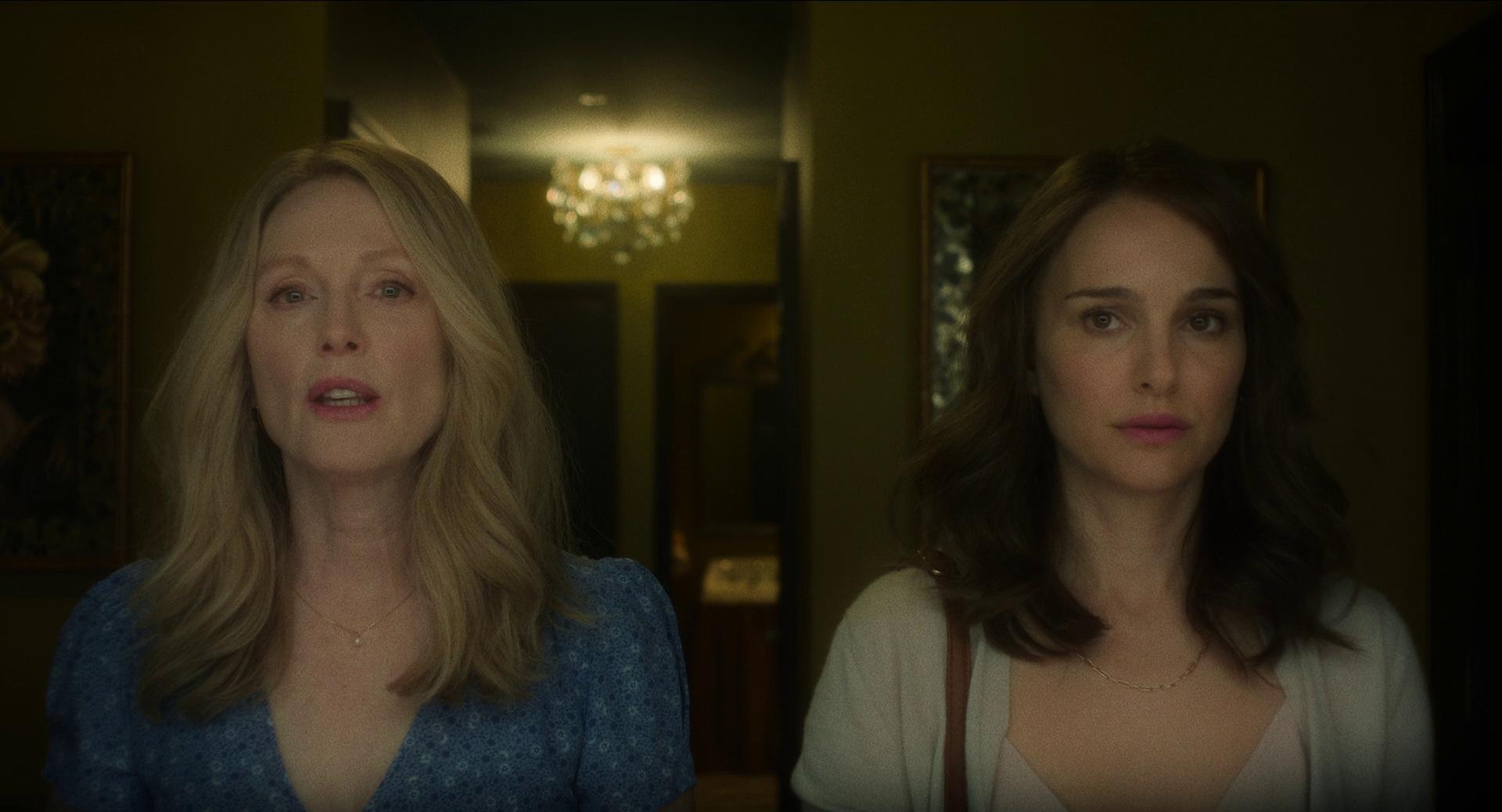

As Portman begins to adopt Julianne Moore’s unassuming lisp and self-absorbed naivety, a parallel contrast emerges between their characters’ outward mannerisms and internal amorality, marking a prime achievement for both actresses. While 1950s Hollywood melodramas are typically Haynes’ main source of inspiration, the probing of unstable psyches here bears the distinct mark of Ingmar Bergman, and follows in the Persona lineage of films that obscure boundaries between strikingly similar women.

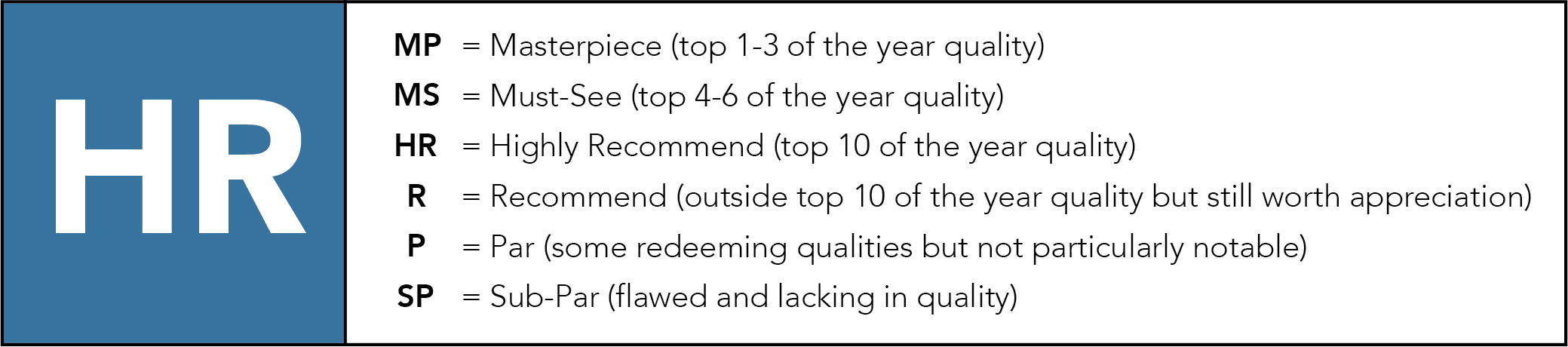

The mirrors that Haynes formally lays throughout his mise-en-scène develop this idea of doubles further, catching their reflections in evocative compositions that suggest a hint of illusory deception, and at times even psychological domination. Behind the neatly patterned wallpaper and lush piano score, dark undertones creep forward to underscore the malevolent artifice of the entire power dynamic, carefully constructed to frame Gracie as an innocent victim of the judicial system. Even though she asserts that it was Joe who first seduced her, we can’t help but notice the glint of self-recognition in her eyes when she goes out hunting, encounters a fox, and shares a silent moment of understanding with her fellow predator.

The frequent cutaways to Joe’s caterpillars are employed with even more acute purpose in May December, tracing them through their chrysalis stage and right to their emergence as monarch butterflies, though this time it is the young husband’s evolution which is bound to Hayne’s primal metaphor. As Joe witnesses his teenage children coming of age and relishing the freedom of youth, he mournfully begins to recognise how much of his own was stolen from him, and the immense betrayal he suffered at a trusted adult’s hands. The trauma hidden behind years of denial begins to break free, and his gradual escape from Gracie’s grip brings the same bittersweet liberation that he offers his butterflies.

Of course though, the entertainment industry would never show such interest in a character of actual substance. Joe’s side of the story is simply not as scandalous as Gracie’s, and he is thus doomed to remain a supporting role in Elizabeth’s cheap, second-hand recount of their illicit affair, the facts of which she can’t quite manage to nail down. The information that Gracie’s embittered son from her first marriage provides about how she was sexually abused by her old brothers becomes the bedrock of Elizabeth’s research, providing a rational psychological explanation for his mother’s actions, but her complete denial of these events muddies the waters even further. Perhaps he is fabricating a story simply to earn himself a movie credit, or maybe it is Gracie who is lying to maintain the illusion of a perfect life – though ironically this lack of a tragic backstory makes her appear even less sympathetic, and her actions unjustifiably cruel.

Either way, Elizabeth finds herself immensely frustrated over the lack of answers keeping her from getting to the heart of Gracie’s character, if there is a heart there at all. With no comprehensible motivation for this actress to cling to, all she is left to play with are hollow mannerisms and an all-too-suggestive snake to stroke as she finally reconstructs the pet store seduction in front of a camera. “It’s getting more real,” she insists after the director calls cut on the third take, though clearly her attempt to reconcile easily digestible entertainment with a complicated reality is futile. After all, the amiable masks that Elizabeth and Gracie wear to conceal their parasitic habits are no replacement for a genuine, empathetic understanding of humanity, or even art for that matter. Within May December’s strange duality of life and fiction, all that matters is the artificial image of feminine sensitivity projected by its two women, winning the unearned sympathy of neighbours and audiences alike through performances of astoundingly shallow proportions.

May December is currently playing in cinemas.

Pingback: The Best Films of 2023 – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Female Actors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 25 Best Female Actors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green