Bradley Cooper | 2hr 9min

To work as a conductor and composer is to live two separate lives, according to Leonard Bernstein in Maestro. Within the privacy of his studio, he sits alone and crafts eloquent musical expressions that allow a self-examination of his own soul. This is the grand inner life of a creator, he explains to the journalist interviewing him, in direct conflict with the majestic outer life of a performer who stands on stages in front of enraptured audiences. This is where his polished genius is displayed without the trial and error, inviting people into a world that is constantly evolving according to each new note, rhythm, and shift in dynamics.

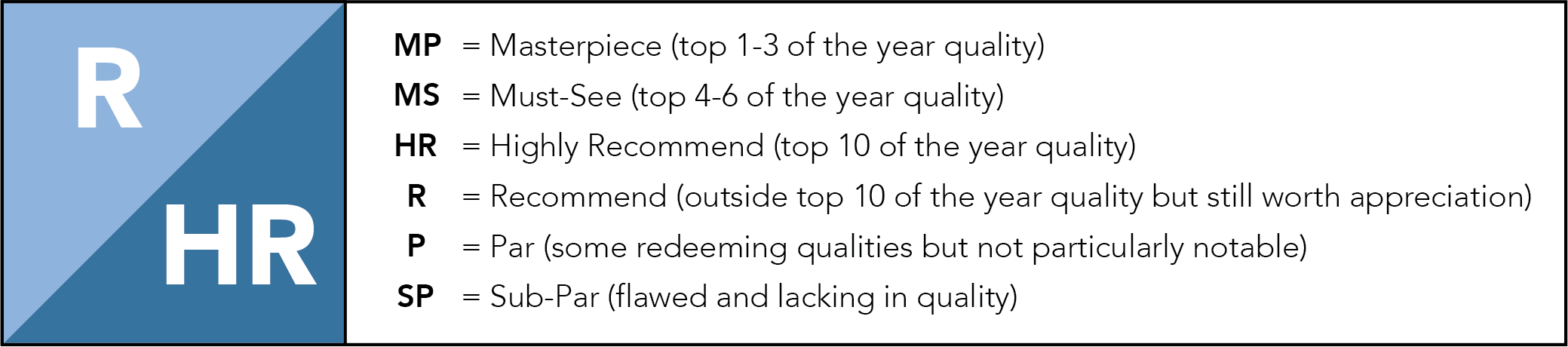

To carry around both personalities is to virtually become schizophrenic, Bernstein jokes to the journalist interviewing him, and yet the conflict between both identities is clearly a point of reckoning. “I love people so much it keeps me glued to life even when I’m most depressed,” he elucidates, putting his overwhelming dependence upon the company of others into words, though he almost immediately follows that up with the darker side of the same statement.

“I love people so much that it’s hard for me to be alone.”

Perhaps this is why Bradley Cooper sees Leonard’s complicated relationship with his wife and muse Felicia as the key to uncovering his creative essence, where both private and public lives chaotically collide. His affairs with other men become temporary antidotes to that haunting fear of loneliness, and within his marriage to Felicia, they also become an open secret. The bitterness that mounts behind closed doors and within resentful glances can only stand to be contained so long, and erupts in one particularly nasty exchange when he brings a younger boyfriend home for Thanksgiving.

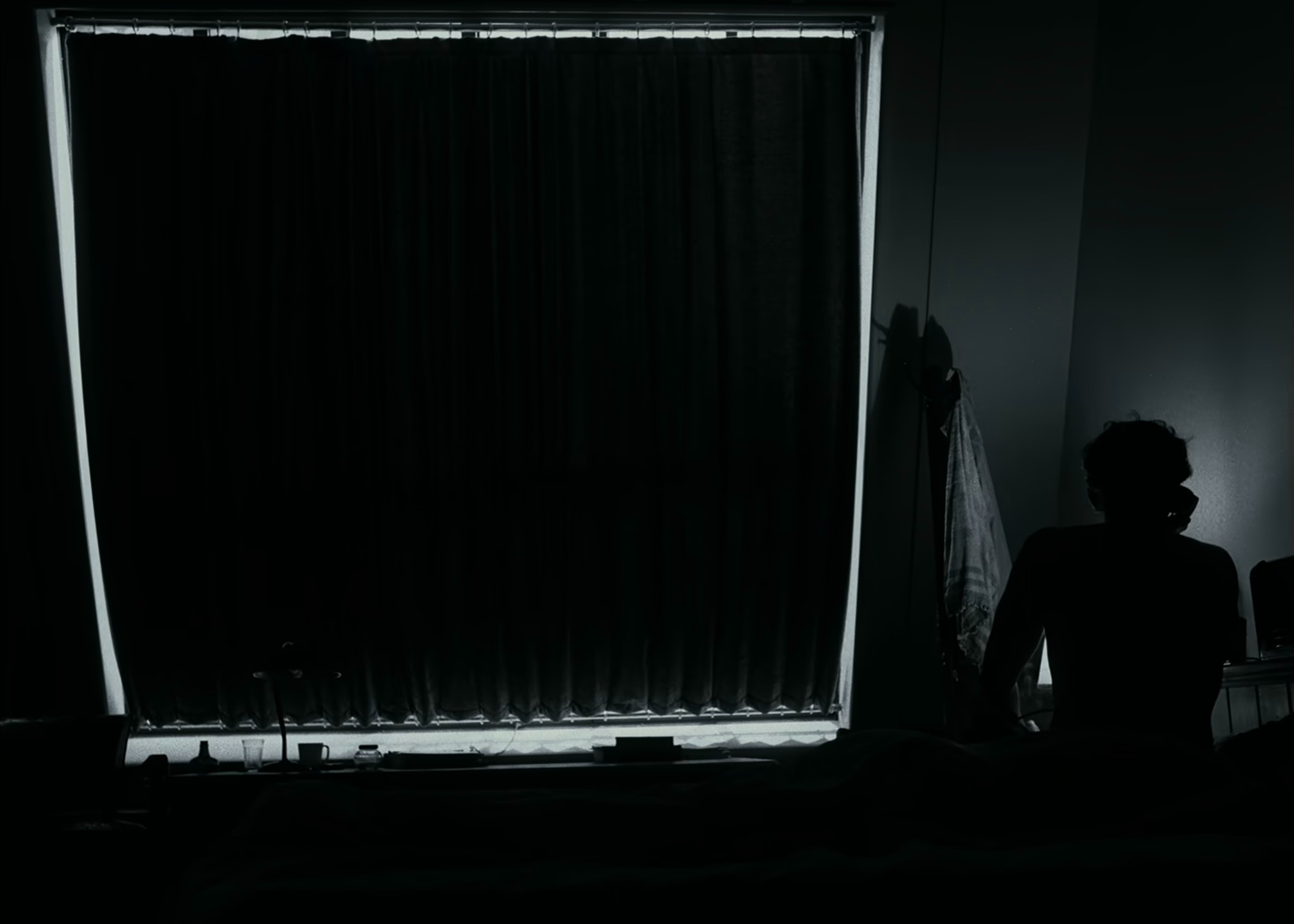

Drawing visual inspiration from Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage, Cooper stages them at the extreme edges of a wide shot in the New York City apartment where they quarrel, and hangs on the frame for several minutes. As Felicia points out his habit of framing affairs as intellectual nourishment, the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade passes by the window in the background, taunting Leonard with views of a joyful public celebration that he would much rather be at. He can’t help but love people, he weakly asserts, and yet he too can see the future she predicts where he simply dies “a lonely old queen.”

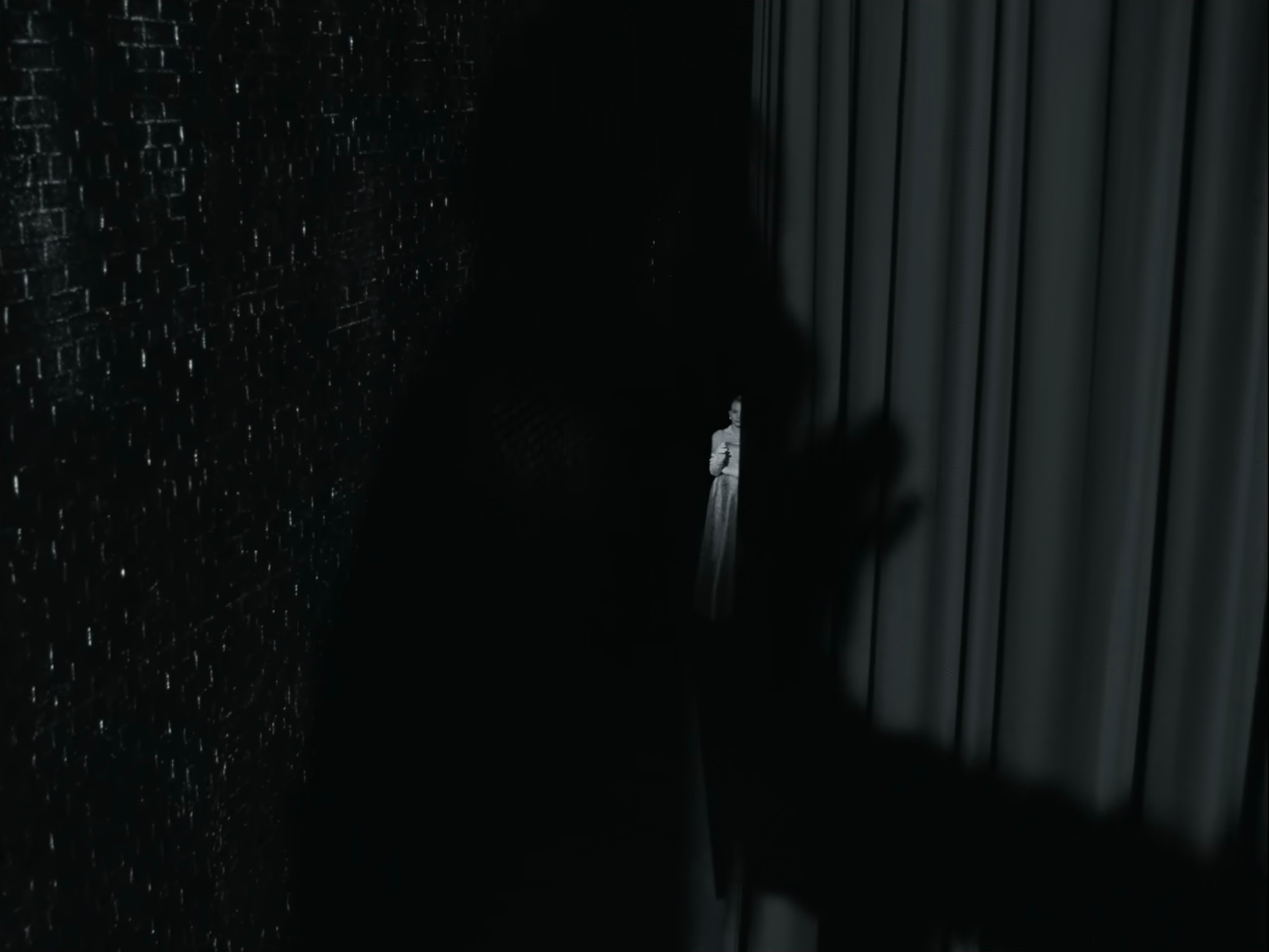

Cooper shows an impressive restraint in many domestic scenes like this, using slow zooms and static shots on beautifully staged compositions that continue long past the point most contemporary directors would have cut to a reverse shot or close-up. By opting for longer shot lengths and a steadier pacing, he is specifically styling Maestro after the pristine, glossy look of classical Hollywood films, even using the narrow Academy aspect ratio and a sharp shift from black-and-white to colour photography with the dawn of the 1960s. At its absolute strongest, he uses the lighting and framing of this polished aesthetic to craft cinematic paintings of Felicia and Leonard’s troubled relationship, brightly illuminating her as she stands in wings of the theatre while consumed by her husband’s giant shadow conducting the orchestra. Carey Mulligan’s performance is undeniably strong, but there is more conveyed through images like these than much of her dialogue.

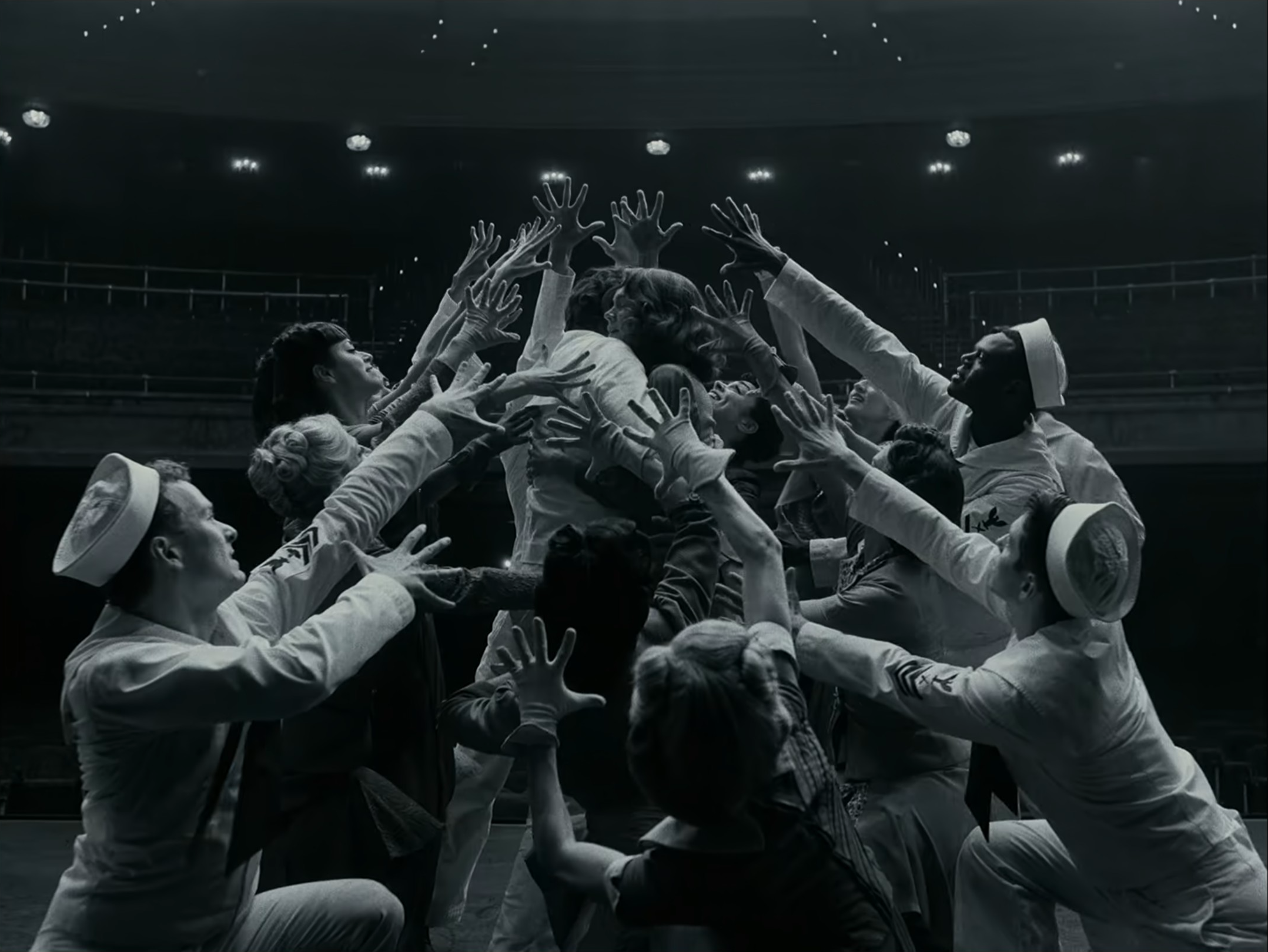

When Cooper does kick the energy of the film up a notch, he does so with formal purpose, separating these bursts of theatrical vigour from his home life. Overhead shots keep pace with him as he excitedly runs to take his place on a stage, and when he stands in front of an orchestra, he throws his entire body into the act with magnificent passion and control. This is the image of Leonard Bernstein that the public recognises and that the maestro himself indulges in, engaging with the souls of audiences stirred by his evocative musical expressions, and Cooper has rarely been better than he here as he disappears into the role.

At the peak of both his performance and direction, he smoothly navigates his camera in a majestic six-minute take through the orchestra during Bernstein’s famous conducting of Mahler’s ‘Resurrection’ Symphony at Ely Cathedral, tracking in on his sweaty, grinning face and lively movements before travelling around the edges of the stage. It is nothing less than a demonstration of virtuosic brilliance, capturing a magnetic presence that the camera can’t seem to tear itself away from, while elsewhere Cooper interprets his passion with greater abstraction in a romantic dream ballet set to the song ‘New York, New York.’ Even when he is at home or in a restaurant, the theatre is apparently never far away, as Cooper’s transitions between locations are so slick that they virtually become invisible within unbroken shots.

Where Cooper’s vision for Maestro begins to falter is in the same place as many other biopics, as he covers such a large span of the musician’s life to the point of stretching the narrative thin. Fortunately, there is just enough of a focus on his and Felicia’s relationship to hold it together as a decades-spanning study of his deepest loves, addictions, and insecurities, none of which really fade over his lifetime but rather take different forms in shifting circumstances.

The sensitivity and support that Leonard unselfishly gives to Felicia as she battles cancer might be surprising given his past unfaithfulness, and yet it is also entirely consistent with his claim that his overwhelming love of others is also his greatest struggle. On the darker side of this, he also never quite breaks his habit of grooming young male students following her death, as he instead runs even faster from the loneliness that threatens to consume him in his old age. The genius that Cooper so vividly captures in Maestro is one that can see no other option than to lead double lives of a conductor and composer, a family man and philanderer, a heterosexual and homosexual – yet whether by the pressures of social convention or personal inhibition, even he cannot reconcile the contradictions of his own humanity.

Maestro is currently streaming on Netflix.

Pingback: 2024 Oscar Predictions and Snubs – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 25 Best Male Actors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green