Alexander Payne | 2hr 13min

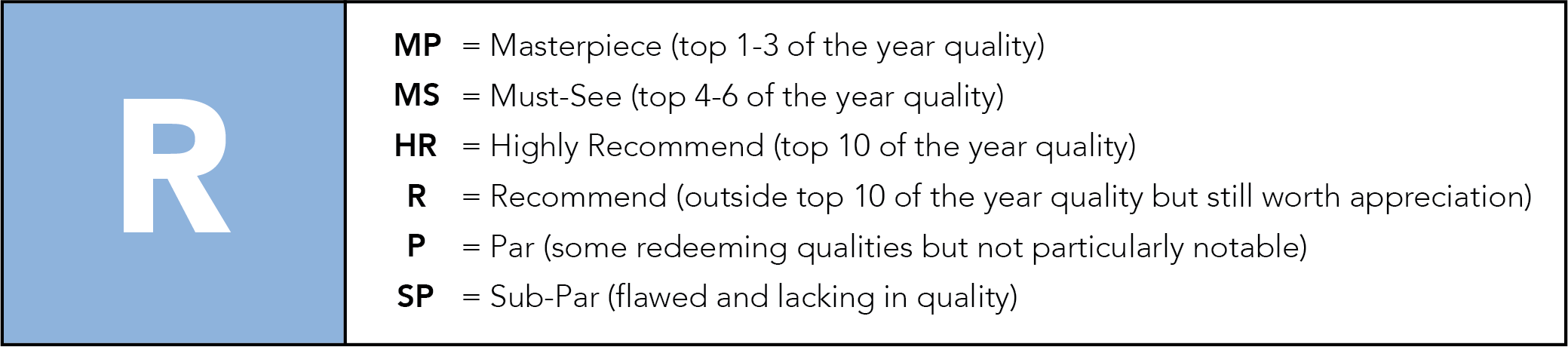

The students and teachers of all-boys boarding school Barton Academy have no issue letting Mr Paul Hunham know that he is by far the least liked member of staff. He is a hardline traditionalist who rarely gives high grades, refuses to let his class off early on the last day of semester, and freely dishes out creative insults with unfettered bluntness. Quite understandably, those few students who won’t be returning home for the Christmas break are dreading spending it with him instead. Even outside of school term, he continues to impose study and exercise schedules, and rules over their downtime with unwavering rigidity.

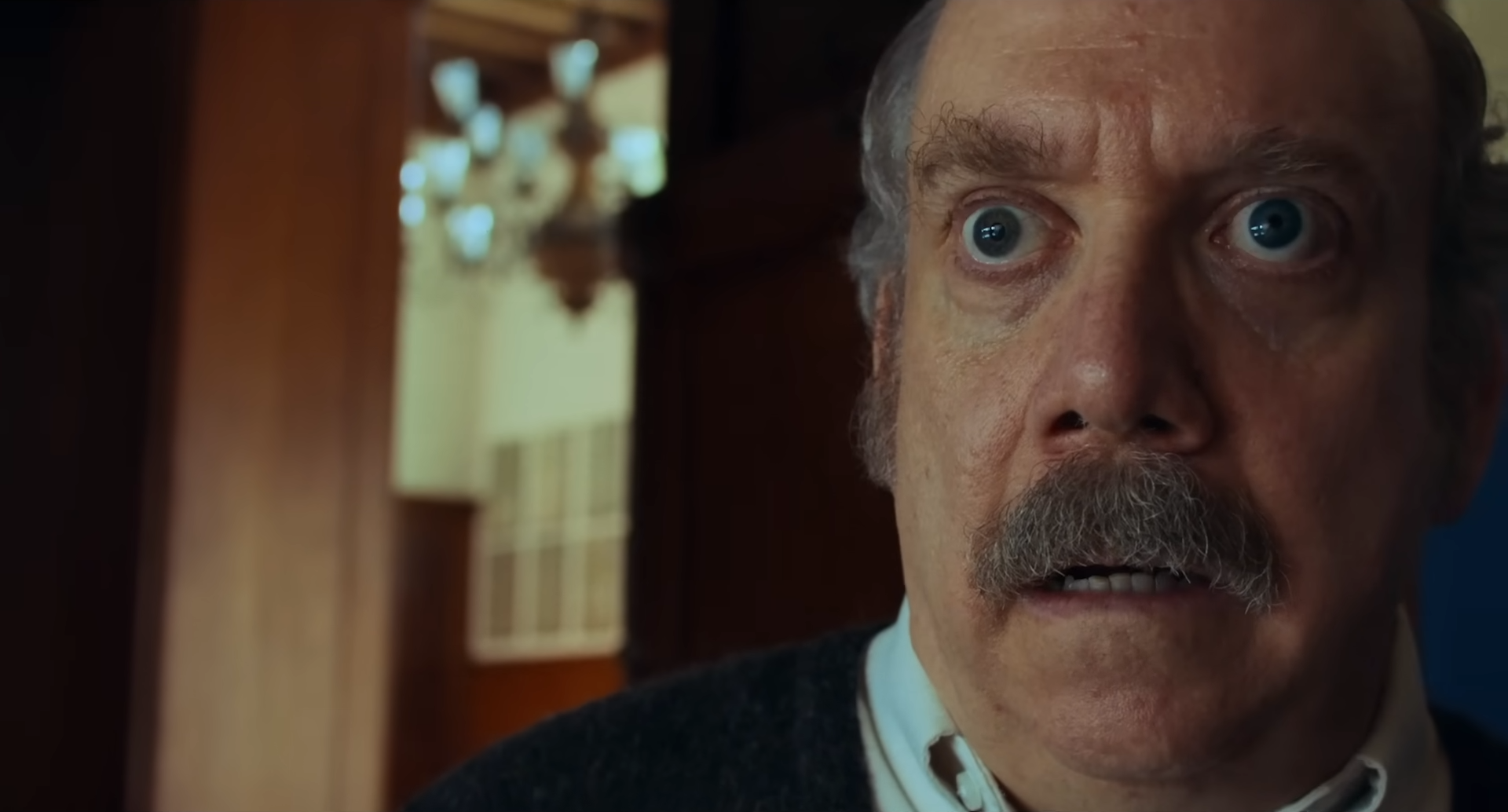

It is through the warm, festive magic of The Holdovers though that Paul crucially separates himself from the hostile teachers of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off or The Breakfast Club. Alexander Payne instils his protagonist with an amiable sincerity that is scarce to be found in so many contemporary films, using both style and narrative to call back to the cinema of the era that these characters are living through. Just as America was caught between its mid-century innocence and a horrific grappling with the Vietnam War in the 1970s, so too are the teenagers of Barton coming to grips with a harsher world than they once believed, making for a coming-of-age film that unites generations in common emotional struggles.

More specifically, it is the comedy-dramas of Hal Ashby that inspire Payne’s direction in The Holdovers, many of which were in conversation with the decade’s political issues. The relationship that forms between Angus and Paul obviously lacks the romance of Harold and Maude, and yet the bond they form similarly transcends a significant age gap, while the appearance of Cat Stevens’ song ‘The Wind’ within the 70s pop soundtrack draws the connection even deeper. The long dissolves that link scenes in their unauthorised excursion to Boston also recall the snowy, cross-state road trip of The Last Detail, blending frozen landscapes and close-ups in transitions that thoughtfully evoke a distinct time and place in American history.

The film grain that Payne emulates in his digital cinematography takes the nostalgia of 70s cinema a step further, but more than anything else it is the complex character work which richly embodies the decade’s counterculture. Most of the boys’ parents are relegated to minor roles here, setting off on winter vacations that leave their children emotionally isolated over the Christmas break and struggling to find any meaning in the holiday season. Angus’ relationships with his mother, father, and stepfather are particularly delicate, forcing him to shield a raw, wounded heart behind layers of white lies.

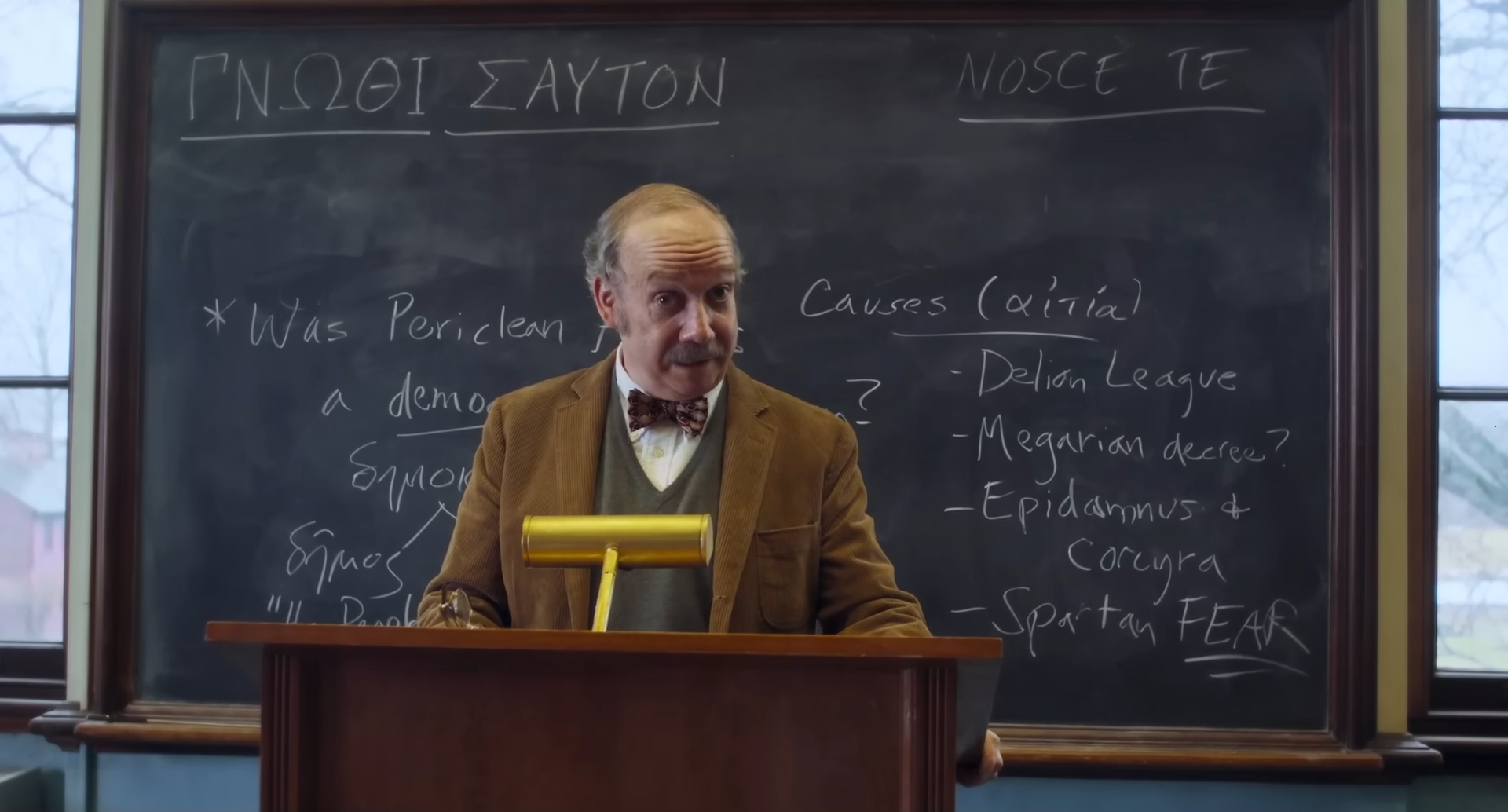

That his cantankerous classics teacher turns out to be the most well-equipped adult in his life to nurse those afflictions comes as a surprise to Angus, and perhaps even more so to Paul himself. He too has learned to hide his insecurities, though his defence mechanism manifests as a front of cerebral confidence, awkwardly inserting ancient historical facts into conversation and even outright lying to an old college classmate about his academic career. It is the small details of Paul Giamatti’s performance that develop this professor into such a nuanced portrait of middle-aged loneliness, from the lazy eye that keeps others guessing which one to look at, to the shyness around women that hints at a life of celibacy. Should he let the air of intellectual authority disappear for even a second, then he might just be exposed as a social outcast whose entire self-worth rests on his job.

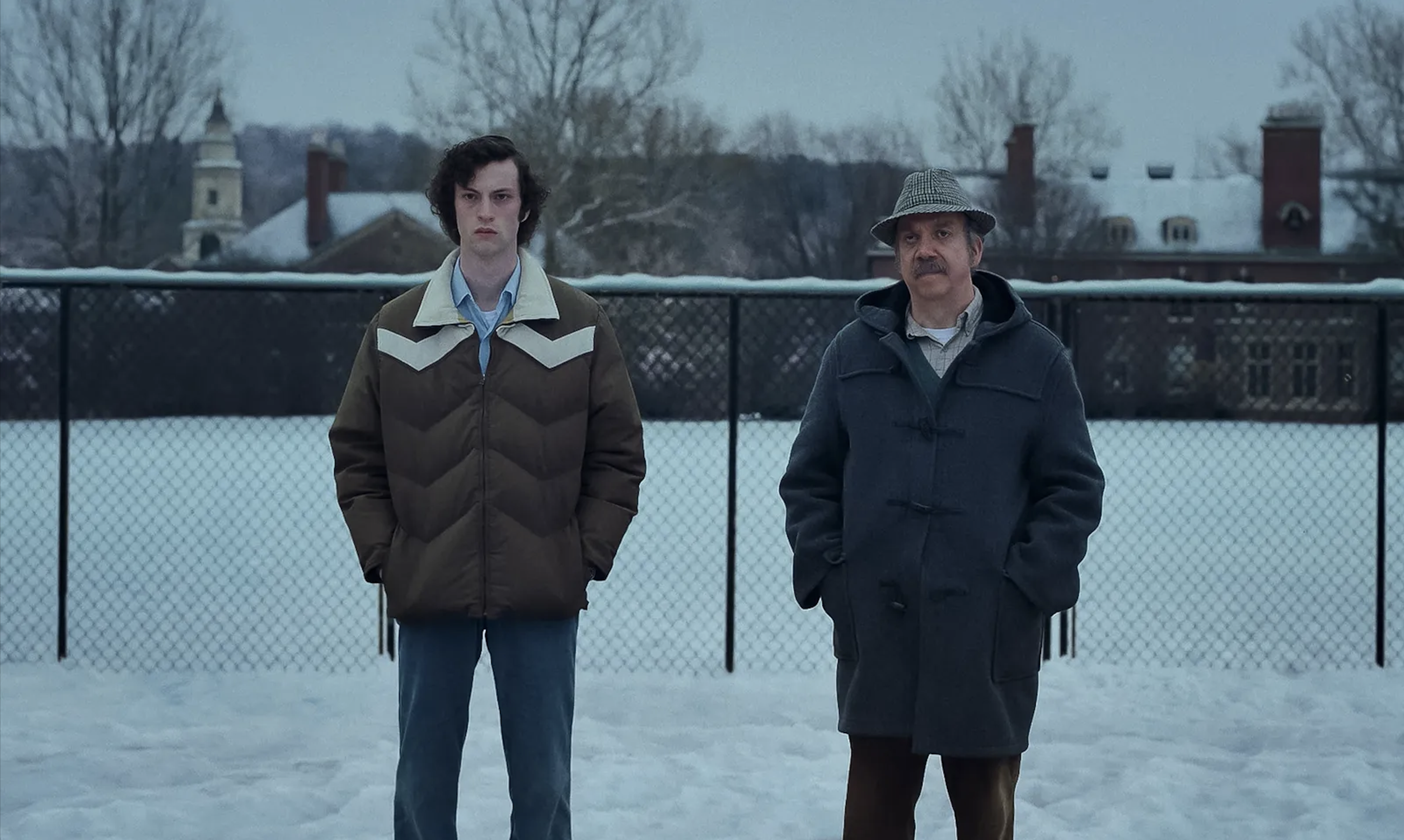

If there is anyone worth opening up to though, it is Angus. While they are trapped inside the school alone with head cook Mary Lamb, they slowly drive each other insane, and Payne delights in the gags that ensue from their rivalry. The rapport that all three build over time is carefully earned, even if the time stamps which mark the passing days are formally weakened by their relatively quick drop-off. This is a film of small moments of connection, transforming forced obligations into genuine desires to fill the voids in each other’s lives. For Angus and Paul, this takes the form of a father-son relationship, while for Mary it is the loss of her child in the Vietnam War that keeps her grieving at work over the Christmas break, and which sees her subconsciously take on a maternal role in this surrogate family of outsiders.

Payne’s comedy is rarely extraneous to these relationships, but often serves to bring these characters together in moments of levity or, at the very least, high-pressure situations that they might look back on with humour. Driven to rebel out of sheer frustration, Angus taunts Paul with a forced chase through the school hallways, but ultimately fails to subvert the power structure when he dislocates his shoulder. Angus’ decision to take the blame for the incident and save his teacher is more than just a step towards reconciliation for them – it is paid back in full by Paul at a critical point in his own character arc, sacrificing his ego and rigid principles for his student’s future. It is not by discipline, but rather through compassion and mercy that he makes the biggest impact of his teaching career, without ever losing that sardonic wit that gives Payne’s festive film its amusingly cynical edge. By the end, it is almost impossible not to give into the effortless, authentic charm of The Holdovers, as Paul, Angus, and Mary transform what so many consider the loneliest holiday of the year into a season warmly dedicated to its most distant outcasts.

The Holdovers is currently playing in cinemas.

Pingback: 2024 Oscar Predictions and Snubs – Scene by Green