Andrew Haigh | 1hr 45min

When lonely screenwriter Adam meets his mother and father for the first time in over 30 years, it seems as if barely any time has passed at all. The reunion comes as a cathartic experience, letting them catch up on significant life events they have missed, apologise for past misgivings, and appreciate each other as fully rounded humans, despite his parents being preserved in the exact same state that he remembers from right before their deaths. They are quite literally living in the past, coming to terms with his queerness in an era where AIDS is running rampant, and not being fully aware of the details that surround their fatal car accident. Grief has suffocated Adam into a repressed silence for many decades, and only now can the adult orphan find closure with those who inadvertently started it, opening him up to new relationships and experiences that he had always walled himself off from.

Therein lies the second narrative thread of All of Us Strangers, completing this four-hander with Adam’s far more outgoing neighbour, Harry. His drunken, flirtatious visit one night to Adam’s apartment is greeted with shy reservation and gentle rejection, though our protagonist’s interest is officially piqued and a relationship soon begins. Andrew Scott and Paul Mescal’s chemistry is beautifully realised in their complementary performances, basking in the simmering excitement of new love. When they aren’t out partying in London’s nightclubs, they lay in each other’s arms back home, discussing their shared experiences of growing up homosexual in the 1980s and the amusing semantic difference between being “queer” and “gay.”

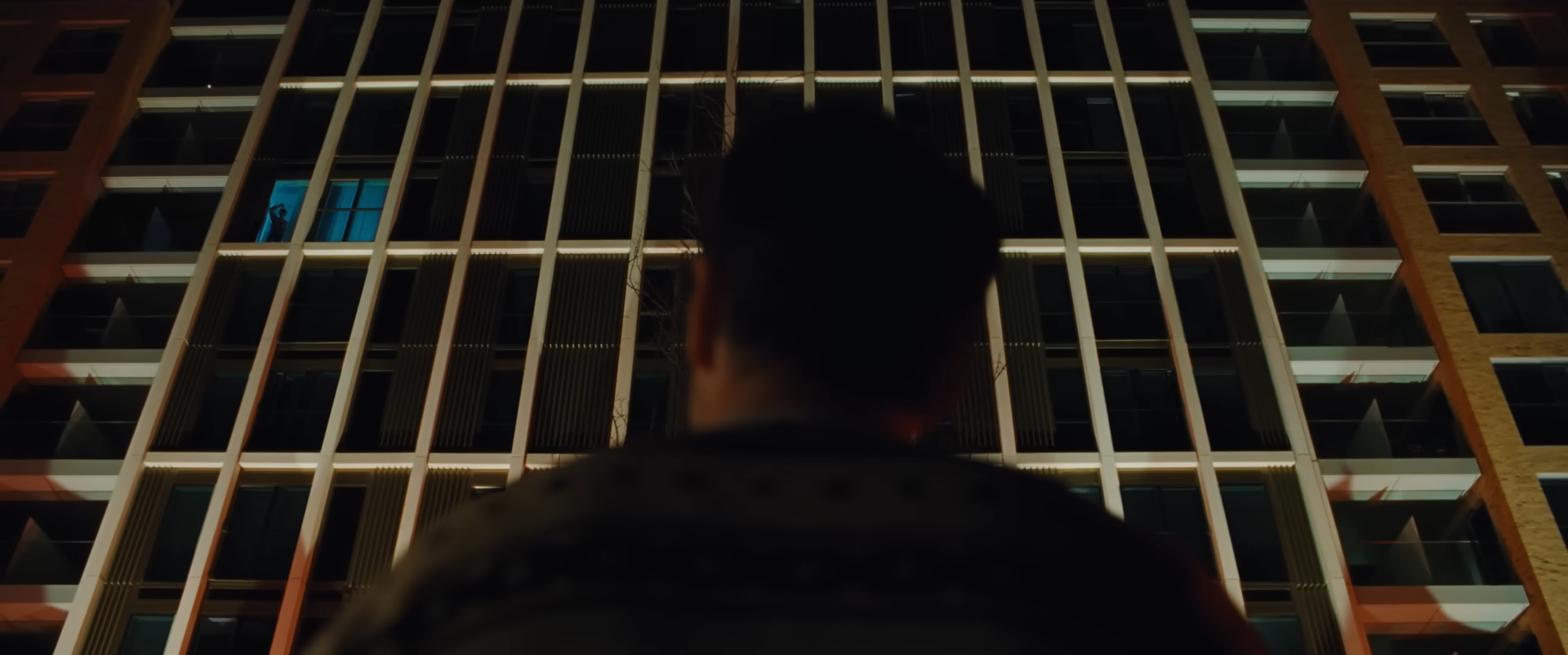

For a time, All of Us Strangers is caught in a repetitive structure alternating between Adam’s interactions with his parents and his dates with Harry, though Andrew Haigh suffuses each scene with an ambiguous, dreamy quality that becomes increasingly disorientating. Visually, he dimly washes Adam’s home in a burnt orange lighting, romantically consuming them in the colours of a sunset that never seems to fade. Haigh’s use of mirrors also makes for some fractured compositions that frequently isolate Adam within his apartment, and alternately create countless doubles inside his building’s elevator that symbolically surrounds him with illusions on all sides. After all, what are these visions of his parents if not imaginary extensions of himself?

The existential malaise that encompasses Adam’s life continues even when he ventures out into public, suggesting a hint of Sofia Coppola’s delicate meditations that contain her characters within lonely bubbles. Haigh languishes in the tranquillity of his visual storytelling, drifting along soothing waves of synthesised drones and long dissolves that steadily disintegrate our sense of time, until we too can barely grasp the difference between Adam’s dreams and reality. While high on ketamine at a club, visions of his long-term future with Harry give way to further hallucinations, and from there each new scene takes us deeper into the surreal layers of his subconscious.

As Adam lies in his parents’ bed and listens to his mother speak of old regrets, an overhead shot slowly zooms in on their faces, before slyly letting those figments of his imagination disappear altogether. Travelling through the London Underground, he sees the warped reflection of his younger self scream into the tunnel’s black void. Stirred by a newfound confidence, he finally decides to introduce Harry to his parents, and his delusion is painfully brought to light when they both find his childhood home dark and empty.

Haigh commands his magical realism with subdued wonder and unease all through All of Us Strangers, persisting even through its genuinely shocking snap back to reality in the final scenes that reveals the full, heartbreaking extent of Adam’s daydreams. Human connection is a saving grace for those carrying enormous emotional burdens, and without it many may simply fade into the miasma of modern living. At least in its absence, Adam can find solace and guidance through its imagined substitute, wistfully summoning up ghosts of childhood memories and alternate lives that he might have once led.

All of Us Strangers is currently playing in theatres.

Pingback: The 25 Best Male Actors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green