Francis Ford Coppola | 1hr 34min

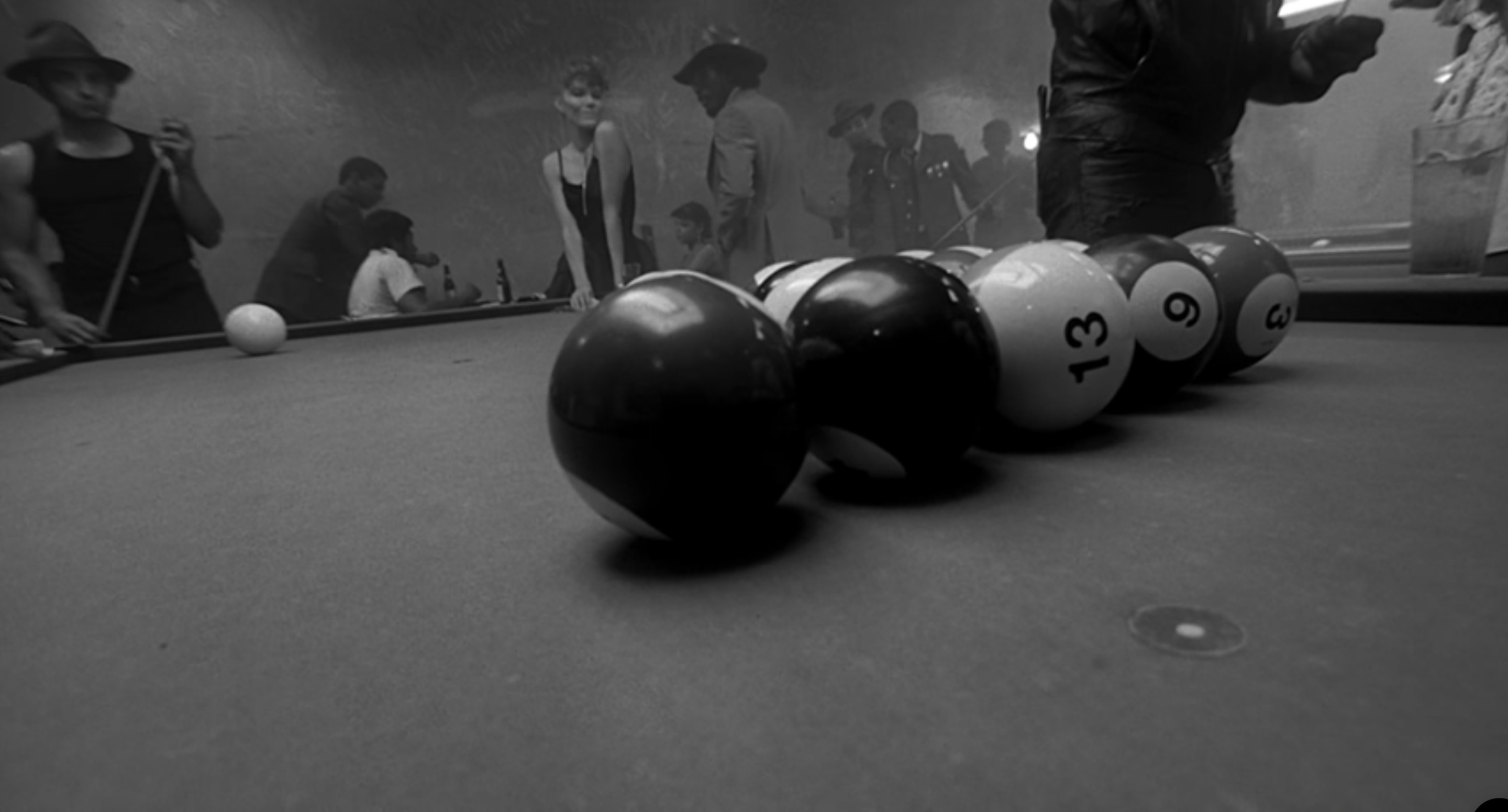

The legendary Motorcycle Boy may not be our protagonist in Rumble Fish, though this doesn’t keep Francis Ford Coppola from filtering the urban landscapes of 1960s Oklahoma through his eyes. Whatever visual restrictions are imposed by the greaser’s colour blindness are drastically offset by the dreamy expressionism elongating every angle, the timelapse footage slipping through hours in a few seconds, and perhaps most significantly, those tiny splashes of blue and red swimming through the local pet shop’s aquarium.

It isn’t that these vivid Siamese fighting fish are somehow exceptions to the Motorcycle Boy’s optical deficiency, but they occupy his attention like nothing else in this world. As he peers through the glass with his little brother Rusty James, Coppola’s camera traps both men and fish inside the same tank, drawing an oppressive visual comparison to the confinement and aggression of their fellow juvenile delinquents. Freedom is distant, but if they are to find peace with themselves and stop fighting their own reflections, it may be their only hope.

“They belong in the river. I don’t think that they would fight if they were in the river. If they had the room to live.”

Some time ago the Motorcycle Boy was a notorious gang leader, and the graffiti that bears his name all over town is a testament to that larger-than-life reputation. Having recently returned from his vagrant travels, he has experienced a taste of the liberation that he now desires for these fish. His emotional transformation is unmistakable in Mickey Rourke’s mellow, tender performance. He is not looking to vent any pent-up frustration, as so many other boys are. He brushes off accusations of madness with a gentle smile, and speaks with a soft voice that quells the frenzied fury around him. Twice in Rumble Fish do we watch him nurse a wounded Rusty James back to health, modelling a sensitive masculinity that seeks to heal rather than destroy, and very gradually he inspires his brother to follow him down a similar path. His colourblind view of the world is not a restriction, we come to realise, but perceives far more of its beauty than anyone else can imagine.

Coming out on the heels of The Outsiders in 1983, Rumble Fish was the second S.E. Hinton adaptation to be released that year. Both stories are based in the same setting of 1960s Tulsa, exploring the emotional depths of young greasers looking to escape the violence surrounding them, and yet the sheer gap in artistic quality between the two is so shocking that it is hard to believe Coppola directed them in consecutive shoots. The Outsiders was the greater commercial success and is far more accessible to mainstream audiences looking for an easy watch. Rumble Fish may have been more polarising, but it is also the far greater cinematic accomplishment on every level, bringing an augmented visual aesthetic to Hinton’s writing that resonates deeply with its paradoxical adolescent yearning for both excitement and stability.

Adding onto that uncertainty a sense of urgency pressing these young people to sort their lives out before growing up, and the world at large seems to be working against them at every turn. Coppola weaves in his timelapse photography as a powerfully formal representation of this, cutting away to clouds racing across reflective surfaces and shadows rapidly stretching along the ground, while Stewart Copeland’s percussive score ticks and beats out propulsive rhythms in the background. The clocks that Coppola lays all throughout his mise-en-scène continue this poetic exploration of time invisibly passing by, even using a giant one as a backdrop to Rusty James’ confrontation with a police officer, and calling back to the dream sequence of Ingmar Bergman’s Wild Strawberries with its eerie lack of hour and minute hands. As teenagers, abstract concepts like time aren’t exactly at the forefront of their thoughts, yet local barkeeper Benny offers a sharp perspective in his voiceover that acutely pinpoints the transience of their youth.

“Time is a funny thing. Time is a very peculiar item. You see when you’re young, you’re a kid, you got time, you got nothing but time. Throw a couple of years here, a couple of years there, it doesn’t matter. The older you get you say ‘Jesus how much I got, I got 35 summers left.’ Think about it – 35 summers.”

For the young men and women of Tulsa who are not yet facing their mortality though, this irrational distortion of time is not to be pondered, but revelled in. Coppola is not one to exclude us from its subjectivity either – everyday life in Tulsa is visually heightened to an incredible degree, warping the proportions of the city’s infrastructure with an incredibly deep focus, canted angles, and split diopter lenses. Coppola’s world is in a perpetual state of commotion and contortion that verges on film noir, flooding scenes with smoke, flashing lights, and spraying water that serve no other purpose than to create incredibly dynamic imagery, and navigating these elements in long, evocative tracking shots. The dreamy atmosphere is laid on thick, loosely detaching us from reality as Rusty James envisions scantily clad women lying on classroom shelves, and deliriously hallucinates his spirit flying from his body and across town to observe the flattering grief left in wake of his imaginary death.

In essence, Coppola transforms a setting that most people would view as a monotonous into a fantasy land, dreamed up by mavericks wishing to break free of convention and conformity. To many small-minded locals, this eccentricity is something to be shunned, though there is a wisdom to be found in those who see its value. Rusty James’ father may be drunk and idle, but he is still among the few who sees his eldest son’s open-mindedness as a gift.

“Every now and then a person comes along, has a different view of the world than a usual person. Doesn’t make ‘em crazy. I mean, an acute perception, that doesn’t make you crazy.”

Right after Dennis Hopper slurs his way through this counsel though, he adds a caveat, drawing a very thin line in his precise wording.

“However, sometimes… it can drive you crazy, an acute perception.”

In this same conversation, we begin to understand where he gained this insight, and where the Motorcycle Boy might have inherited his personality – not from his father, but from his mother who abandoned her children while they were still young. Outsiders like these can only be contained in their loneliness for so long before drastically breaking free, frustrated by others’ narrow thinking. The Motorcycle Boy could have easily followed in his mother’s footsteps and run away a second time, but his enormous empathy turns him down another path instead, roping Rusty James into his mission to let the Siamese fighting fish swim free into the river.

If there is one mark that Motorcycle Boy wants to leave on the world though, it is not the liberation of these vibrant red and blue fish, but the liberation of Tulsa’s restless youth – or at the very least Rusty James. He does not seek to uphold any personal legacy, and yet it nevertheless forms in his absence, keeping his pacificist principles alive while his persecution by a prejudiced society is taken to its bitterly logical end. A single police gunshot cuts off the score’s pounding beat at the moment it takes his life, leaving only Rusty James to pick up the fish now flopping on the grass, and finish what his brother had started. The communal mourning that he once imagined in a dream manifests at last, though this time not for him, as Coppola’s sombre long take floats along a line of familiar faces gazing upon the Motorcycle Boy’s body with sorrow and horror.

The final shot of Rumble Fish does not announce itself with the same audacious energy of Coppola’s expressionistic angles or timelapse footage, and yet the tranquil stillness of Rusty James’ arrival at the coast his brother always longed for marks a subtle departure from the chaos of Tulsa. For once there is very little depth to Coppola’s photography, as a telephoto lens instead flattens the liberated teenager’s silhouette against a vast, endless ocean, and time seems to slow down. The world of Rumble Fish may not be meant for those unusually perceptive misfits living far outside the status quo, but the best the rest of us can do is follow in their footsteps, boldly journeying beyond the borders and standards of a modern society slowly driving each of us mad.

Rumble Fish is currently available to rent or buy on Apple TV, YouTube, Google Play, Amazon Video, and the DVD or Blu-ray can be purchased on Amazon.

Pingback: The 50 Best Directors of All Time – Scene by Green