Michael Mann | 2hr 11min

It is said in Roman mythology that when Saturn learned of a prophecy foretelling his downfall at the hands of one of his children, he set out to eat each of them as they were born. As a man desperately searching for an heir to his business and family name, Enzo Ferrari may not possess great sympathy for the King of Gods, and yet the journalist who draws this comparison may not be so far off given the devastation that is visited upon young men looking to earn the entrepreneur’s admiration.

Unlike those unfortunate souls, Enzo would much prefer to sit above the fray of motor racing as an engineer and businessman, coaching the drivers of his automobiles rather than risking his own life behind the wheel. He understands their addiction to the sport all too well, and uses that to feed their sense of competition by telling them individually that they alone each have the best chance of winning against each other. This is ”our deadly passion, our terrible joy,” he grimly declares, though his romanticisation of its lethal danger is not easily missed.

With Ferrari premiering at the Venice Film Festival in 2023, the eight years that separate it from Michael Mann’s previous film Blackhat is the longest period of dormancy in his career, beating out the six years which had divided that espionage thriller from Public Enemies. That this is the story he chose to break the drought is somewhat surprising given the crime and action films that otherwise define his career, but this is not the first time he has ventured into biopic territory either, having previously used the genre to examine the legacy of boxing legend Muhammed Ali. In this instance, the awe he holds for the founder of the Ferrari brand is clearly a prime interest for him, stretching all the way back to the early 2000s when he first began exploring a potential film adaptation. Enzo is exactly the sort of morally compromised man whose ruthless pursuit of a singular objective aligns with many of Mann’s greatest characters, and yet who also hides all his pride, shame, and sorrow behind tinted sunglasses.

After Adam Driver’s recent stint as the head of the titular fashion brand in House of Gucci, his second shot at playing another Italian entrepreneur of the twentieth century is a moderate improvement. His talent is undeniable as he remarkably passes off as a man in his late 50s, outshining a poorly miscast Shailene Woodley as his mistress Lina Lardi, though often being outdone by the raw fire of Penélope Cruz. Much of her storyline in Ferrari as his wife Laura is spent furiously narrowing in on her husband’s secret family, drawing her determination from a bottomless well of grief over the recent passing of their son. That Enzo is so prepared to replace the deceased Alfredo with his illegitimate child is an insult to his memory, she vehemently asserts, desperately trying to preserve the remnants of her broken family.

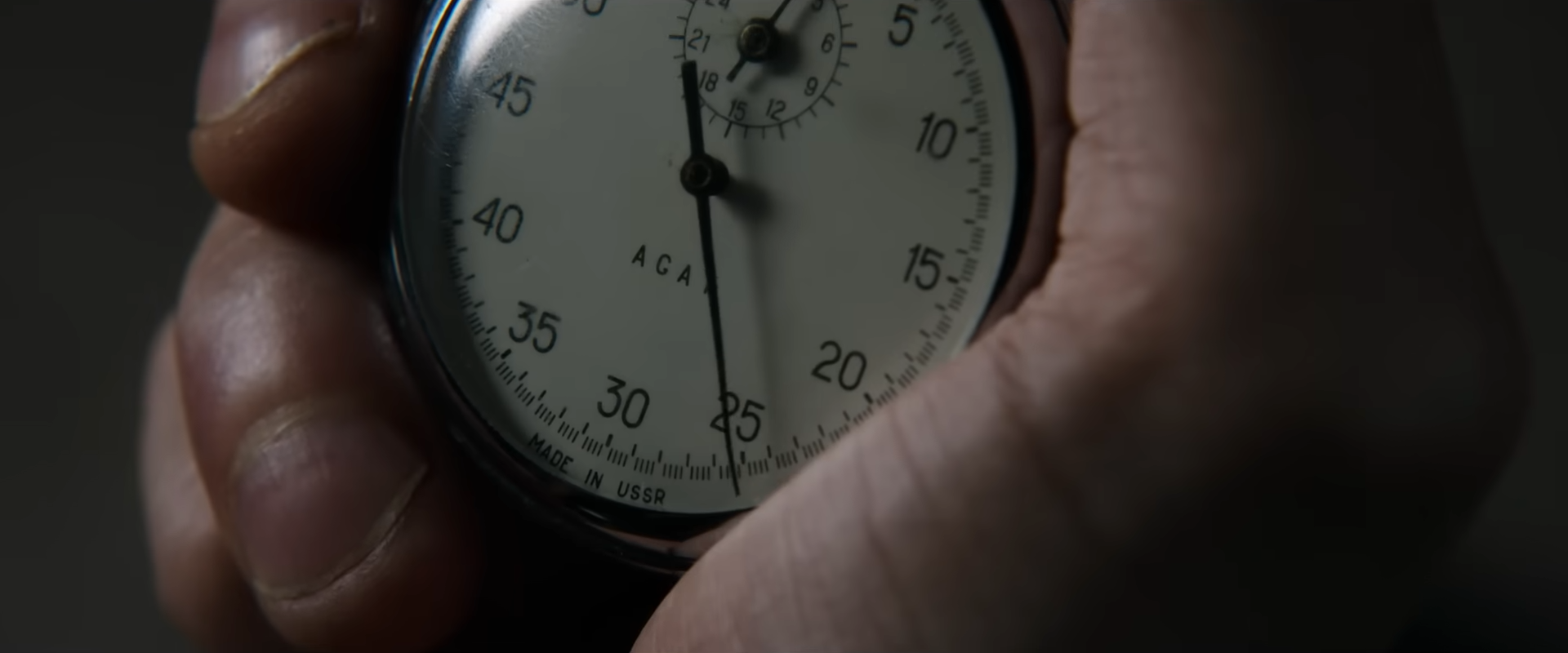

Perhaps the blame that Laura places on Enzo for their son’s terminal illness is unjustified, but it certainly reinforces that image of a God feasting on the deaths of his children. If we are to view his drivers as his descendants too, then the fact that he took one of their widows to be his mistress is entirely damning. As the untouchable head of the Ferrari family, he exerts an influence which even pulls the Roman Catholic church itself into his orbit, becoming a Don Corleone figure in a scene that alludes heavily to The Godfather. As Enzo listens to a homily about car manufacturing, the sounds of his competitor’s vehicles can be heard clearly from a nearby test track. Stopwatches are withdrawn from the congregation’s pockets as they line up for communion, vigorously ticking along with the score while Mann sharply intercuts between both locations. In place of God, it is Ferrari who reigns over this sacred building, holding greater respect for speed, efficiency, and victory than human life.

Nowhere do the consequences of this idolatry becomes so devastatingly apparent than in the Mille Miglia of 1957. This was historically the last time the open-road, thousand-mile endurance race was played out, and for very good reason. Where the rest of the film suffers from flaws in its pacing, these thirty minutes carry a thrilling momentum in its razor-sharp editing, even when we cut to scenes of Enzo, Laura, and other characters following the competition from a distance. Dispersed throughout this heart-pumping sequence too are some of the film’s finest long shots, basking in the green valleys and dusty orange skies of Italy’s countryside, before moving into the cobbled streets and narrow streets of Rome. Once again, the sound of ticking stopwatches weaves into the music score with urgency, while dolly zooms queasily warp the road ahead of Enzo’s driver Alfonso de Portago through the quiet rural commune of Cavriana, luring him to an awful fate.

European car racing history is littered with tragedies, and the Mille Maglia was especially no stranger to participants and spectators losing their lives in fatal collisions. That Mann so unflinchingly presents the accident which officially brought an end to this specific race is profoundly shocking. The blown-out tyre which causes it may be caught in slow-motion, but the car’s violent cleaving through a crowd of bystanders happens so fast that the only hope we can cling to is that death came instantly and painlessly.

Whether the environment of ruthless competitiveness that Enzo fostered was responsible for Portago’s decision against changing his worn tyres is delicately uncertain, and later leads into a court trial that Ferrari brushes over far too quickly in its abrupt ending. To Mann though, the details of his manslaughter charge and its eventual dismissal are unimportant. Far more fascinating is Enzo’s reaction as he visits the gruesome site where eleven lives were claimed, including those of five children. Like a coroner examining a mangled carcass, he picks through the wreckage of his race car, barely even turning his eyes to the crushed and severed corpses around him. If the media vilifies Enzo as a deity who props up his legacy by feasting on the lives of his own children, then perhaps they are merely carrying through the justice that was never delivered in court. For all of Ferrari’s narrative unevenness, the god of conquest at the centre of Mann’s modern mythologising makes for a compellingly thorny subject, leaving behind a long trail of bodies in his blood-stained ascent to cultural immortality.

Ferrari is currently playing in theatres.

I think Adam Driver gives quite easily the best performance in Ferrari actually. His internalization here is needed to counteract Penelope Cruz’ fierceness. But he looses it in one scene talking about his kids’ demise and is a walm calm presence in the scenes with his illegal child and handling racing management. I think Cruz is overused here. That scene with Ferrari’s mother alone is pretty rough. Her best scene is probably the one she visits the bank and try to find out about Ferrari’s transactions. Also Woodley barely has anything to do here. The focus is on Ferrari’s illegal child whenever he visits them. She only basically has one proper scene where I thought she wasn’t more imposing enough (too soft). But I didn’t thought she was bad or a hindrance in any way.