Alfonso Cuarón | 1hr 46min

To Alfonso Cuarón, the story of Mexico’s political turbulence at the end of the twentieth century is not best understood through a historical epic or biopic. Y tu mamá también is far more interested in capturing its cultural and class tensions through the friendship of two teenage boys, completely indifferent to the dwindling power of the Industrial Revolutionary Party which held onto the presidency for the past 70 years, as well as the nation’s increasingly globalised economy. The world may be changing around them with wide-reaching implications, but they would much rather spend their time chasing women and upholding that self-devised, fraternal manifesto they claim is sacred, and yet so frequently stray from.

Despite their ignorance, Mexico’s modern politics are intimately intertwined with their personal relationships. After all, Tenoch’s upper-class background brings with it an air of superiority, seeing him use his foot to lift the toilet in Julio’s working-class home in much the same way he does at a shabby motel. Conversely, Julio is self-conscious at his friend’s more impressive house, lighting a match after using the bathroom. These adolescents may be hormonally aligned in their love for masturbation, sex, and all things masculine, but Y tu mamá también is acutely attentive to those differences that surface over the course of their beachbound road trip, specifically motivated by the prospect of charming their newest companion – the beautiful, 28-year-old Luisa.

By 2001, Cuarón had already established a solid filmmaking career moving from Mexico into Hollywood, and yet his greatest success to date comes here with a modest $5 million budget. In place of highly curated studio sets, beautiful long shots of rural Mexican countrysides, roads, and beaches connect us to the nation’s natural terrains and infrastructure, often placing the horizon towards the bottom of the frame while dusty blue skies and soft orange sunsets stretch out over detailed landscapes. His usual palette of murky greens is still occasionally present in his lighting and production design too, but Y tu mamá también is far more naturalistic than his previous films, opting for handheld camerawork that freely navigates scenes in long takes.

This is a specific sort of world-building that Cuarón would further explore in the smooth tracking shots of Children of Men and the steady pans of Roma, disengaging from his central characters to examine the details of their surrounding environments. In this instance, frivolous conversations remain audible even while our eyes wander elsewhere, drifting several times past family photos hanging on walls during phone calls, and elsewhere swinging inside a car to glance back at a pulled-over vehicle. Cuarón is sure to never quite sit long enough on these distractions to give us anything more than a vague glimpse – after all, Tenoch, Julio, or Luisa would much rather keep their heads down than consider their implications, though we are still left to wonder whether this traffic stop is a drug bust, an abuse of police power, or both.

Our travellers will encounter many more fragments of Mexico’s sprawling culture on their journey, some steeped in tradition with villagers stopping passing cars to pay a toll to their “little queen” dressed in bridal white, while others hint at widespread corruption. In a stroke of formal genius, Cuarón matches these diversions to the narration as well, frequently muting his diegetic sound before dropping in its commentary. These annotations are often as trivial as the camera’s fleeting observations too, offering brief cultural insights which mean little on their own, yet which together weave a textured landscape of poverty, celebration, and profound torment.

“If they had passed this spot 10 years earlier, they would have seen a couple of cages in the middle of the road… and then driven through a cloud of white feathers. Shortly after, more crushed cages, filled with bleeding chickens flapping their wings. Later on, an overturned truck, surrounded with smoke. Then they’d have seen two bodies on the road, one smaller than the other, barely covered by a jacket. And next to them, a woman crying inconsolably.”

On one level this narration positions us like readers of a novel, expanding the world through an omniscient literary voice, though this subversion of the narrative’s first-person continuity also bears great resemblance to Francois Truffaut’s formal experimentations during the French New Wave. The similarities to Jules and Jim especially are numerous, right down to the story of two friends being in love with one woman, and so it is also through Cuarón’s narration that we gain deeper insights into those thoughts they would rather keep hidden.

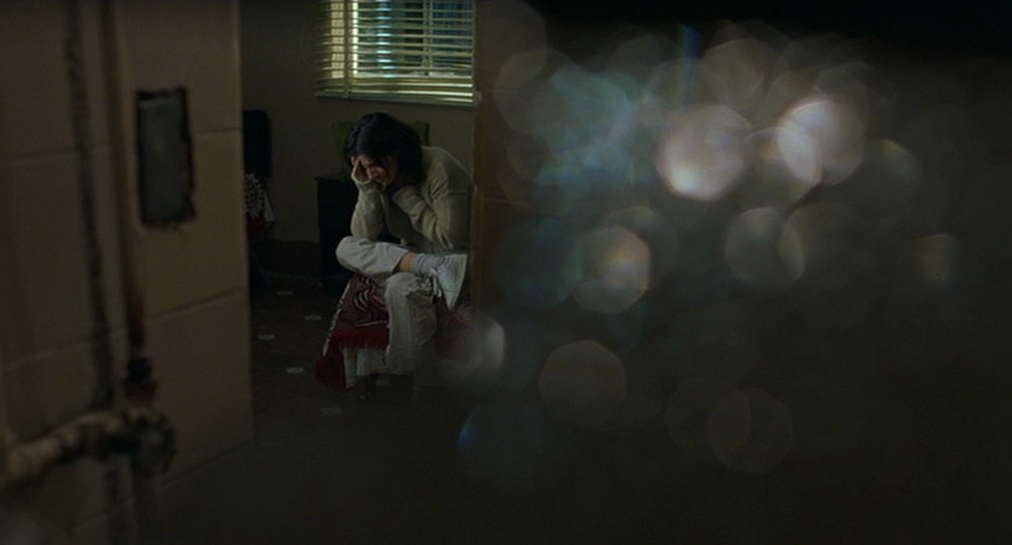

For the secretive Luisa, this is a particularly crucial conceit. As a funeral procession passes by, the narrator notes the existential concerns rising in her mind of how long she will be remembered after dying. We don’t know it at the time, but this is more relevant to her psychological state than we can imagine – she is suffering from terminal cancer, and this entire trip is one last hurrah to embrace life before it slips away. She may be more mature than her male companions, but she is just as adrift, and so it seems are many others they encounter. At one point, the narrator adopts future tense to reveal what is in store for a friendly fisherman who takes them in, and given the changing economic landscape, it does not look bright for him either.

“At the end of the year, Chuy and his family will have to leave their home, because a new luxury hotel will rise in San Bernabé. They will relocate to the outskirts of Santa María Colotepec. Chuy will attempt to give boat tours, but a collective of Acapulco boatmen supported by the local Tourism Board will block him. Two years later, he’ll end up as a janitor at the hotel. He will never fish again.”

Tenoch and Julio might not see the point in contemplating the future, and yet Cuarón realises that their attempt at escapism is a political act in itself, refusing to acknowledge the complexities of the real world. As such, they are ill-equipped to face up to their own vulnerabilities and flaws as well. Their manifesto may forbid sleeping with each other’s girlfriends, and yet they do so anyway. They may openly share feelings for Luisa, but her first sexual encounter with Tenoch stings Julio all the same. Luisa might comfort Tenoch over his poor performance in bed, but he still takes it as a shameful weakness in his masculinity. In fact, almost any time some wedge is driven between these friends, sex is involved. Given the amount of it going on too, there is good reason for the constant conflict.

Only when these immature boys reach a point of self-acceptance and honesty does sex become pure, and perhaps the only straightforward thing in an incredibly complicated world. As they speak about their affairs for the first time without inhibition, Cuarón’s camera basks in the green glow of the seaside retreat, eventually following Luisa to the jukebox where she selects a song at random – the soft-rock ballad ‘Si No Te Hubieras Ido.’ Suddenly, she fixes her gaze right on the camera, intimately inviting us into their shared space as she begins to dance, with the boys soon joining her in a passionate embrace.

There is no insecurity, ignorance, or masculine pretence in the orgy that soon consumes them. It won’t be long after this trip that Tenoch and Julio will go their separate ways, and Luisa will tragically pass away from cancer. So too will Mexican politics, culture, and economics continue to shift as the 21st century dawns, subtly contributing to this widening distance between old friends. Within this moment though, the ecstasy of the present is rightfully all that matters. Finally, there arises an equal affection in Y tu mamá también that neither insecurity, hierarchy, nor the uneasy advance of an early grave can suppress. The story of modern-day Mexico may vast, but this tiny coming-of-age chapter is just as formative to its identity as all those other lives caught in Cuarón’s expansive periphery.

Y Tu Mamá También can currently be bought on Amazon.

Nice writing

One thing to chew on: What if the genders of the main characters were reversed?

A lot would really depend on Cuaron, particularly since this was based on reflections and memories of his own youth in Mexico. He clearly identifies with the young men here. I’m not so sure the flipped gender dynamics would be a straightforward one-to-one reversal.

Guess the film would be cancelled on the fly if that were to happen