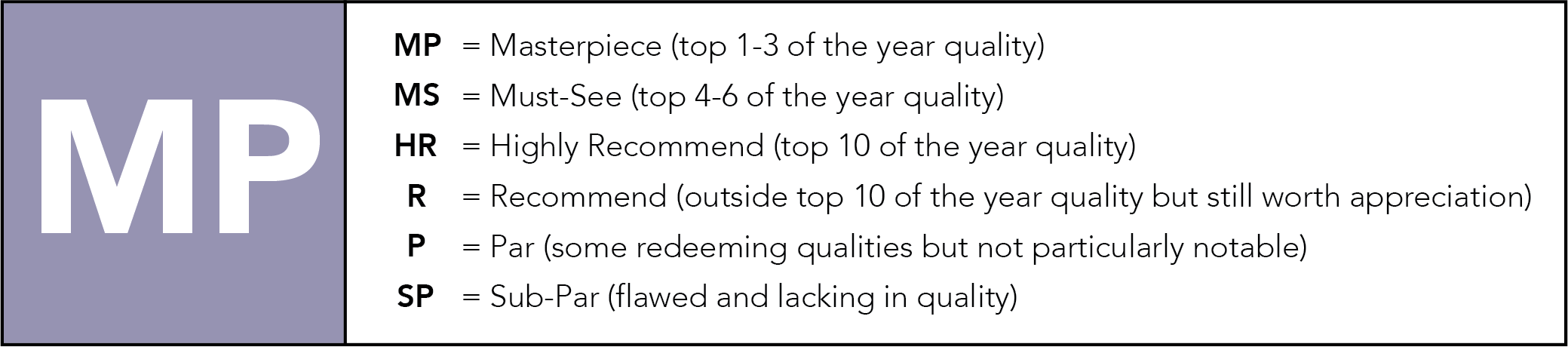

Keisuke Kinoshita | 1hr 38min

There might not be any reliable historical record that the ritual of ‘obasute’ was practiced anywhere outside of Japanese folklore, and yet it is exactly in that heightened, mythical realm where The Ballad of Narayama dwells. In the small valley where the 69-year-old Orin lives with her grandson Tatsuhei, it is tradition for elders to be carried to a mountaintop when they turn 70, and then left alone to perish. This form of customary senicide is not something to be feared, just as the natural course of ageing is not to be shied away from. In fact, Orin’s 33 intact teeth are even a point of shame for her, becoming the subject of a mocking song that is quickly spread between neighbours, cruelly suggesting that she struck a deal with the devil.

“In a corner in the back room

My granny found herself a set of 33 demon teeth.”

The other implication here is that Orin’s appetite is unusually large for a woman of her age, and in this starving village, a gluttony like hers is worthy of public humiliation. Whether for celebration or punishment, singing is the medium through which ideas are shared among the locals, turning rumours into stories, and stories into lyrics. As implied by the title The Ballad of Narayama, narrative and music are strongly intertwined in the film’s very form, paying homage to the traditions of kabuki theatre with a singer introducing scenes and offering poetic commentary. “The harvest in autumn brings sorrow, Even as the rice ripens to a golden hue,” his wavering voice croons to the twanging of his three-stringed shamisen, evoking colourful images of workers labouring away in yellow rice fields that are only outdone by the bright, saturated visuals Keisuke Kinoshita matches to the lyrics.

While his Japanese contemporaries Akira Kurosawa and Yasujirō Ozu were still working in black-and-white around this time, the lesser-known Kinoshita was boldly venturing into the realm of colour cinematography – still a relatively new technology in late 1950s Asia, yet one which has rarely been put to better use than it is here. Within the widescreen Shochiku GrandScope, the earthy yellows and oranges of autumnal landscapes are detailed in vast, painterly compositions, while the colour palette’s eventual shift to greys and whites as snow starts to fall visually ushers in a dreary seasonal change.

Michael Powell’s Technicolor visuals no doubt influenced Kinoshita here, especially with matte backdrops of expansive mountain ranges heavily evoking Black Narcissus, and yet the village’s fluorescent green wash at night and its striking contrast against a bright pink sky makes for an electric contrast that was still quite novel in 1958. The potential of neon lighting was established from there, paving a path for Seijun Suzuki and Mario Bava’s stylistic genre experiments in the 1960s, though it wouldn’t be until Peter Greenaway’s brightly coloured satires in the 80s that we would see another filmmaker adopt and even match Kinoshita’s grand, theatrical artifice.

Because as a visual and formal statement, that is what The Ballad of Narayama is – a heavily curated representation of traditional Japanese storytelling, adapted to a modern medium. Kinoshita never hides the fact that these sets are built on highly controlled soundstages, but also never lets its limitations impose on his vibrant worldbuilding. The lighting dramatically shifts with the sentiment of each scene, at one point dimming to a spotlight on two characters consumed by darkness, and later casting an angry red wash over Orin’s disturbing arrival at a festival with several of her teeth smashed out.

Of course, all of this is entirely in line with kabuki theatre conventions as well, maintaining that invisible fourth wall between the scenery and the viewer as Kinoshita’s camera tracks parallel to the action, and frames interiors in wide shots like dioramas. These sets are incredibly dynamic, often moving walls and props to transition between scenes where one might expect to find a cut, and thereby manipulating our perception of time through theatrical rather than cinematic conventions.

This is not to say that Kinoshita’s direction is stagebound though, as there remains a very sharp attention to detail in his depth of field, mimicking the look of multiplane animations by dividing his frame into separate layers that move at different speeds when the camera drifts past. It is especially the final act of the film following Tatsuhei’s journey up the mountain with Orin on his back that Kinoshita delivers some of his most immaculate cinematic scenery, largely excising dialogue as grandmother and grandson traverse great mossy boulders, cascading waterfalls, and trees that grow more withered with the rising altitude.

Atop the craggy peak, the only sign of life are black crows standing over a number of skeletons – foreboding imagery for sure, and yet this pilgrimage is nevertheless one of serene acceptance. Through the ritual of obasute, generations are united in a cycle of life as enduring as the seasons themselves, which just so happen to shift at the exact point Tatsuhei begins his journey back down. Snow begins to fall, and again we move through the same shots as before, though this time in reverse order and with a soft, white powder concealing the vibrant colours.

Though there may be peaceful closure within Tatsuhei’s family, the burst of violence that disrupts his descent is a culmination of several disputes we have witnessed up to now. His neighbour Matayan is at a similar age as Orin, and yet he does not embrace his encroaching death with such grace. Conversely, his son couldn’t be more ready to rid himself of the old man, finally resorting to dragging his fearful father up the mountain against his will. The brutality and selfishness of these villagers was also firmly established earlier with their lynching of a starving man who tried to steal food, and now as we watch Matayan and his son struggle on a cliff’s edge, we witness another cold-blooded murder. The son’s patricide is an unadulterated perversion of tradition, demonstrating an eagerness to escape the burden of the past rather than let it go with dignity as the conventions of obasute dictate. Grasping for some sort of justice as a bystander, Tatsuhei unleashes his fury upon his neighbour, and eventually succeeds in sending him plunging to his death too.

As if sectioning this entire tale off into a sad, distant dream of Japanese folklore, Kinoshita’s epilogue removes us completely from the vibrant sets and theatrical storytelling that have dominated The Ballad of Narayama up until now. Colours are desaturated into a miserable black-and-white, and for the first time the mountain scenery is entirely authentic, seeing a train pull into a modern-day station. The only indication of the region’s history is etched on a sign, giving the station its name – “Obasute”, or the “abandonment of old people.” A term that once carried great pride has become one of mourning, implying a desertion that is not merely symbolic, but loaded with cruel dispassion. Perhaps we can at least find some solace in the preservation of Japan’s forgotten legends through this cinematic ballad of lush, vibrant colours, healing that division between past and present with a painterly reinvention of theatrical and film conventions as we know them.

The Ballad of Narayama is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, and the DVD is available to buy on Amazon.

Pingback: The 100 Best Shot Films of All Time – Scene by Green