Hayao Miyazaki | 2hr 4min

Given how deeply connected all Hayao Miyazaki’s films are to his sense of childhood wonder, trauma, and pantheistic spirituality, it may be useless singling out any one as his most personal. Still, the fact that The Boy and the Heron unusually captures the storyteller at two different points in his life through a pair of surrogate characters offers new, introspective dimensions to his body of work. For the first time in his decades-long career, his young hero is a boy, Mahito, clearly standing in for his younger self as he escapes into a fantasy world and tries to reconnect with his deceased mother. Fortunately, Miyazaki’s mother did not pass away until old age, and yet the time she spent in hospital during his formative years was clearly a point of reckoning with mortality for the young artist.

Next to Mahito, the mysterious Granduncle who constructed the whimsical realm of cursed oceans and anthropomorphic creatures also becomes a stand-in for Miyazaki, albeit one who is older, wiser, and full of regrets. Both are world builders with the power to shape imagined landscapes into either harmonious paradises or freakish nightmares, though given the innate human flaws of their creators, any setting is likely to be a mix of both. Now coming towards the end of their lives, they both seek out successors to carry their legacies, and yet the question of whether their work can or should be continued looms large. At some point in life, fantasy has run its course, and one must return to reality armed with the new perspectives that have been gained from their dreams.

For Mahito, this is a reality he would much rather forget – the Pacific War has not only killed his mother, but has forced him to evacuate Tokyo with his father, thereby staining his childhood with wartime trauma. His complicated feelings around moving to the countryside and his father remarrying his aunt Natsuko drive him to act out, while the presence of a mysterious grey heron that lives on the estate and an abandoned tower in the yard also tease the possibility of adventurous escape. It only takes Natsuko’s strange disappearance for Mahito to start connecting the dots between each of these, eventually journeying into the tower that was built by her eccentric Granduncle many years ago to discover the surreal universe which lies beneath its foundations.

The whimsical similarities to Alice in Wonderland are evident in this setup, betraying Miyazaki’s adoration of Disney’s animated classics, though the allusions don’t end here either. The influence of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs can similarly be traced right down to the seven eccentric grannies occupying Mahito’s countryside home, as well as the unconscious heroine who lies helpless inside a glass coffin late in the story. Much like his pioneering American counterpart, Miyazaki’s storytelling strengths lie in his manipulation of recognisable archetypes, even as he develops his narrative and symbolism in far more elusive directions.

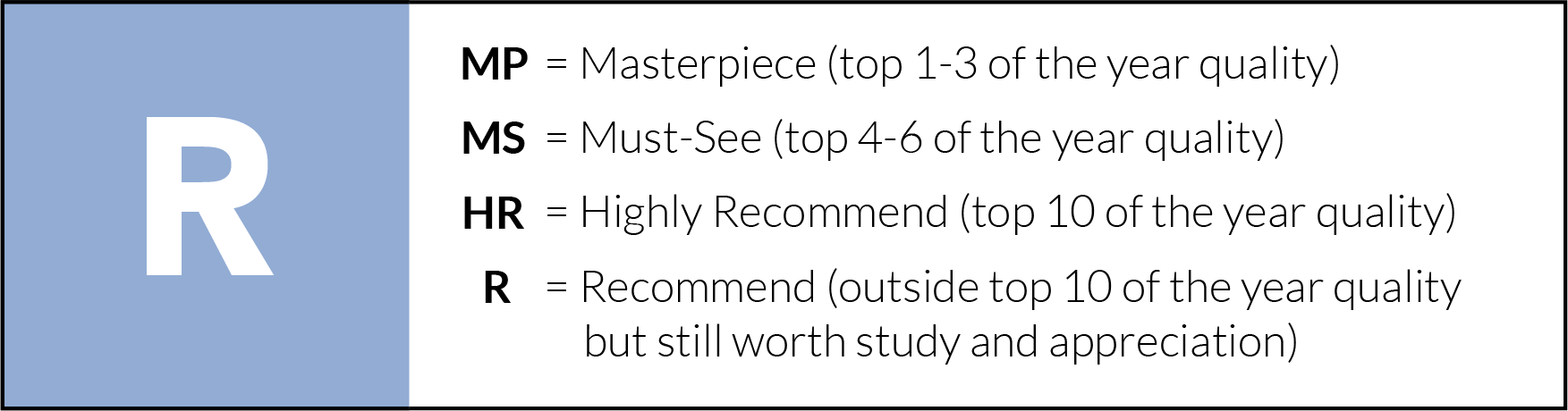

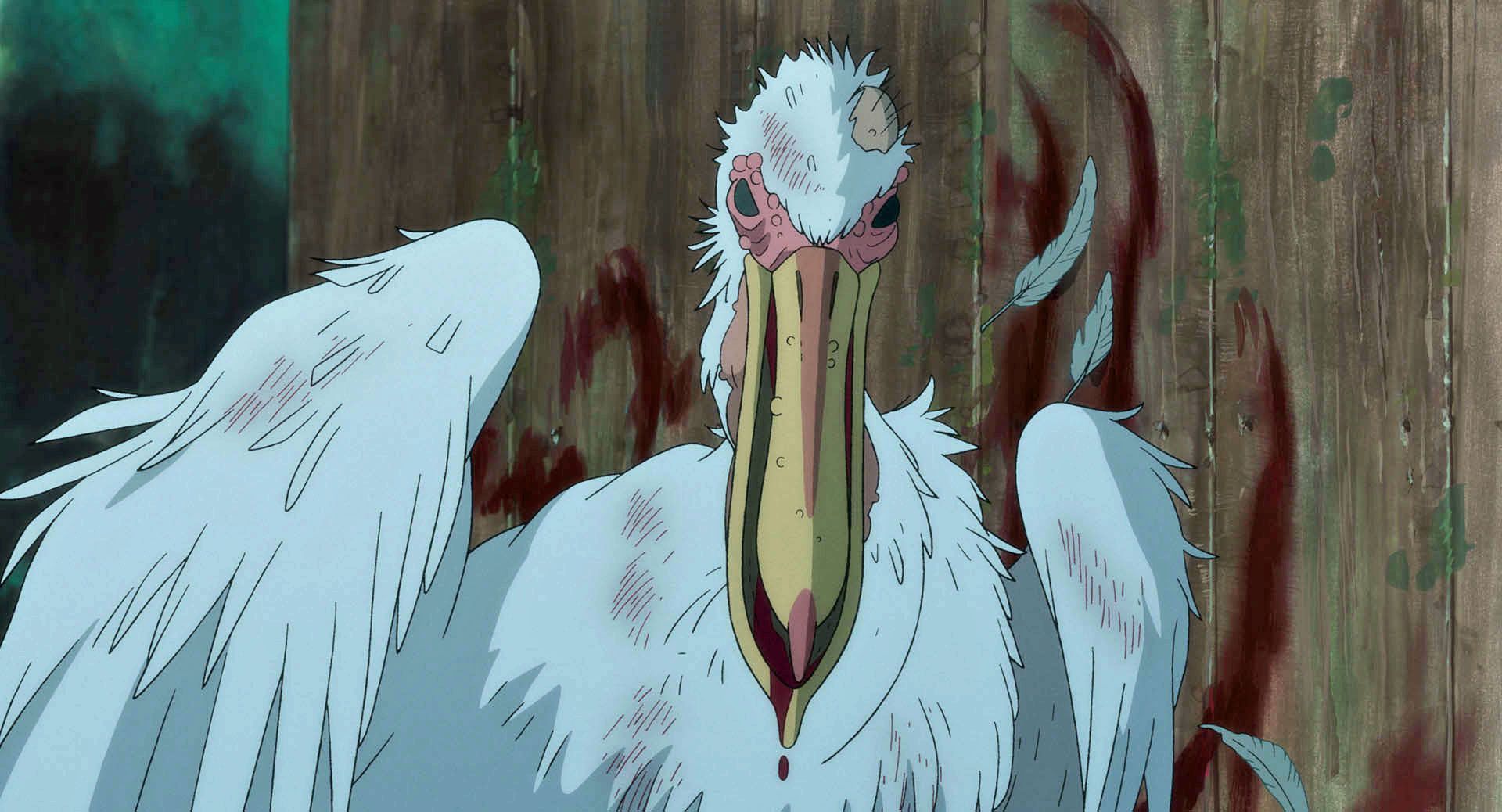

Most prominent among the allegorical icons in The Boy and the Heron are the human-like birds who commonly bear some sort of malicious intent, whether it is the pelicans who eat the souls of unborn babies, or the legion of parakeets who strictly adhere to an authoritarian rule. The raspy-voiced heron in particular becomes a devious twist on Alice in Wonderland’s White Rabbit too, luring Mahito into his world with cruel illusions and grotesquely hiding his true form of a stumpy, caricaturish man in his toothy beak. Though Mahito learns that all herons are liars, he also finds this particular birdman reluctantly becoming one of his closest allies, and incidentally learns from him along the way that not all fabrications are necessarily evil. When the possibility of bringing back his deceased mother is dangled in front of him, he no doubt sees the sham, and yet it is his open-minded curiosity which leads him into a journey of emotional healing through his ancestor’s dreamlike creation.

“I know it is a lie, but I have to see it.”

Miyazaki delights in using hand-drawn animation to construct these layers of verisimilitude, heavily evoking a Salvador Dali-style surrealism when a duplicate of Mahito’s mother eerily melts away, and elsewhere when a dropped rose unexpectedly shatters into tiny pieces. This world operates on a dream logic that distorts the very structure of space and time, leading our young hero down an endless corridor of doors opening to different points in the past, and moulding his deepest fears into life-saving superpowers.

Lady Himi proves to be incredibly significant here, wielding control over the fire that killed Mahito’s mother, and thus turning that destructive force which haunted his nightmares into a force for good. Elemental imagery of air, water, and earth is woven through much of Miyazaki’s fantasy world, and yet it is her whirlwinds of blazing orange flames which consistently provide the most security to Mahito, as well as a maternal guidance that he has sorely missed in his grief.

Conversely, the direction that the Granduncle provides his young descendant is not one of nurture, but rather a burden of responsibility which may not even be worth the continuous effort. Life and fiction must both come to an end, Miyazaki recognises, and yet meaning persists in the wake of both. If The Boy and the Heron truly is his last film, then it is poetic that such a grand adventure into escapist fantasy and back again should be the one to conclude his decades of marvellous, animated world building.

The Boy and the Heron is currently playing in theatres.

Pingback: 2024 Oscar Predictions and Snubs – Scene by Green