Wim Wenders | 2hr 8min

The god’s-eye view of humanity that Wim Wenders grants us in Wings of Desire is refreshingly distant, flying high above the streets, flats, and offices of 1980s West Berlin, before swooping down to tune into the thoughts of its citizens. Like radio waves with a transmitter but no receiver, these streams-of-consciousness aimlessly echo out into chaotic universe. They appear frivolously trivial when taken on their own, and yet they serve an integral purpose in grasping humanity’s mosaic totality.

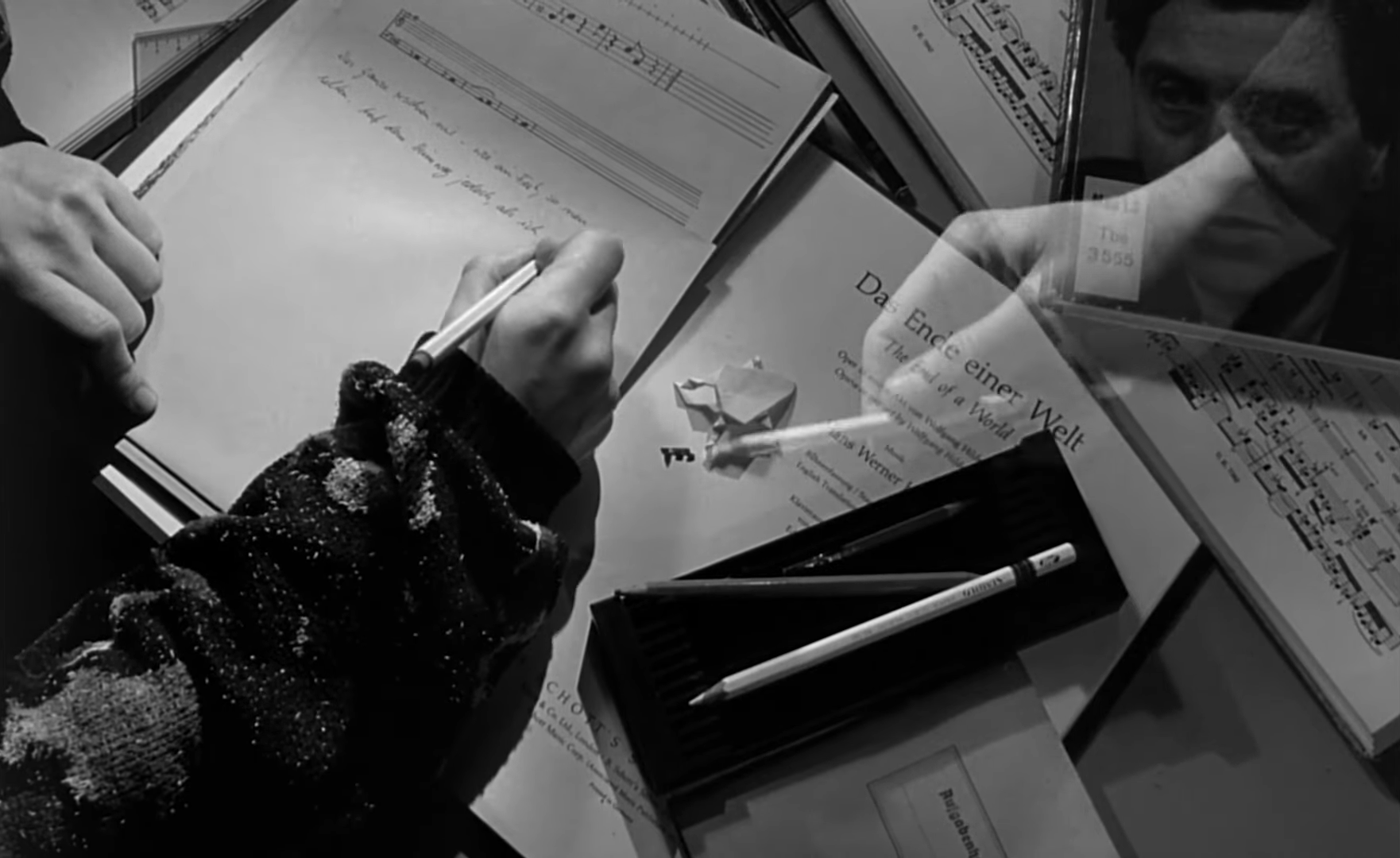

Still, it is not always fulfilling to be as omniscient as those two angels who up until now have embraced their God-given purpose to “Look, gather, testify, verify, preserve” those hidden thoughts that reveal our truest selves. Damiel and Cassiel are purely observers, standing atop buildings and statues with their white, feathery wings spread out behind them, and only ever interacting with mortals when one vaguely senses their spiritual presence. In these moments, fleeting eye contact is made with Wender’s invisible, floating camera, and some intangible expression of hope or wonder crosses their faces. For the angels though, this is the full extent of their correspondence, while Wenders renders more physical attempts at interacting through ghostly double exposures. “To watch is not to look from above, but at eye level,” Damiel contemplates, desperately longing to make the permanent journey from the heavens to a world where one can taste, feel, and love within the limitations of an earthly body.

Like The Wizard of Oz and Stalker before it, Wings of Desire employs a similar formal device of alternating between colour and monochrome cinematography as we switch from fantasy to reality, though perhaps Michael Powell’s deeply philosophical romance A Matter of Life and Death bears closer resemblance to Wender’s take here. From the angels’ foreign perspective, everything appears in an ethereal greyscale – certainly beautiful in its own right, yet failing to capture the broad spectrum of colours that can only be seen when grounded on Earth, where humans relish the subtle shades and hues which come with the knowledge of their eventual passing. Up close, these tiny joys are felt even more viscerally, but only when the melancholy transience of life has also been accepted.

The innocent hope that Wenders draws from these urban landscapes is shaped even further through the social and historical context embedded in virtually every shot as well, infusing his grainy location shooting with an air of poignant whimsy. Unknowingly set right before the fall of the Berlin Wall and bearing the leftover traumas of the Holocaust, Wings of Desire dwells in a space of bleak uncertainty between two world-changing events. Modernist architecture lines derelict streets, disused flats of churned-up mud stretch out for acres, and the Potsdamer Platz that one elderly man recalls from his youth is now spoiled by a graffitied section of the wall dividing Berlin, transforming this once-proud cultural icon of commerce into nothing more than a political partition.

In a brief The Tree of Life-style flashback too, Wenders continues to expand our view of this setting with the creation of its land, when “history had not yet begun.” A single, withered tree stands alone in a rippling lake, imprinting its black shape against a foggy backdrop with no visible horizon, and yet somehow from this total scarcity humanity incredibly evolves into advanced, intelligent lifeforms. The angels have been there since the start to witness it all, and more than anything else in the world, they are rightfully astonished by this incredible miracle of persevering life.

Today, these mortal beings are living testimonies to the city’s complicated past and present, despite very few of them explicitly reflecting on anything beyond the day-to-day minutia. Each one of these minor figures are integral to the silent cinema homage that Wenders is conducting here, building a character out of a metropolis as he thoughtfully calls back to those avant-garde city symphonies of the 1920s like Man With a Movie Camera, lyrically teasing out a visual and aural poetry for lengthy, plotless passages of time. The abstract rhythms of his long dissolves merge with an eerie, polyphonic choir here, running multiple vocal lines up against each other in discordant harmonies, and thereby mirroring the disjointed voiceovers that continue to murmur away in the background.

Like a disembodied spirit, Wenders circles his camera around the heads that project these thoughts outwards before latching onto another, while every so often an unusual exception stands out among the cacophony of whispers that sways these angels to try and forge a connection. Tragically, these attempts are too often in complete vain, as Cassiel’s affectionate contact with a suicidal man in one instance goes entirely unnoticed, leaving the angel deep in tormented grief as he helplessly watches the bearer of messy, jumbled feelings jump to his death.

“The sun in my back, on the left the star. That’s good: sun and a star. Her little feet. Hopping from one foot to the other. She danced so sweetly. We were all alone. Has she got my letter? I don’t want her to read it. Berlin means nothing to me… Havel? Is that a lake? Over there, wedding, or what? The East is everywhere, really. Strange people, they’re shouting. I don’t care. All these thoughts. I’d really rather not think any more. I’m going, why?”

Damiel’s eye is also caught by a disillusioned human who wishes to cast off ties to Earth and fly free, though in a very different manner. In a struggling circus, a French trapeze artist named Marion swings through the air wearing angel wings, and laments her loneliness in a foreign city. Emotionally, she lives in a space halfway between the worlds of humans and angels, unknowingly beckoning Damiel down from the sky as she privately reflects on the strange comfort she feels from some invisible companion.

“I know so little. Maybe because I am too curious. Often my thoughts are all wrong, because it’s like I’m talking to someone else at the same time.”

It is with this line that she turns to the camera and looks us right in the eye – not the first time a character has done this, but certainly the most intimate. Damiel feels truly seen, and that fondness that he previously felt for all humans begins to blossom into singular romantic attraction, directed towards a specific individual.

In a strangely funny diversion from these stories, Wenders spends some time following American actor Peter Falk as he shoots a film in Berlin, before revealing that he too was once an angel who ultimately gave up his wings to be human. Falk plays himself here, expressing an immense gratitude for his rebirth into a body that allows him to smoke, drink coffee, and create art. Wenders’ dedication at the end of the film briefly hints along these lines too, expressing gratitude for his three biggest directorial inspirations – Yasujirō Ozu, François Truffaut, and Andrei Tarkovsky, who he thanks among “all the former angels.”

To humbly bring oneself down to the level of the lowest human and then share its joy through love or art is a truly noble calling, and one that Damiel embraces the moment he wakes up as a human when a slab of metal falls on his head. He bleeds profusely and feels great pain, yet he couldn’t be happier in this moment – any sort of sensation at all is proof of his regeneration into a mortal body, and he can’t help sharing his sudden ability to perceive colours with passing strangers. In essence, his newfound wonder is a tangible extension of the nostalgic poetry formally weaved into the film’s structure, each passage prefacing lyrical ruminations on childhood with the same six words.

“When the child was a child, it was the time of these questions: why am I me, and why not you? Why am I here, and why not there? When did time begin, and where does space end? Isn’t life under the sun just a dream? Isn’t what I see, hear, and smell just the mirage of a world before the world? Does evil actually exist, and are there people who are really evil? How can it be that I, who am I, wasn’t before I was, and that sometime I, the one I am, no longer will be the one I am?”

Cassiel is not wrong to feel that he has more to accomplish as an angel, thus choosing instead to remain behind, but of the two Damiel is clearly the one with the least regrets as begins his new life. When he finally approaches Marion, she once again looks straight at the camera, but this time Wenders’ colour photography captures the blazing red tones of her outfit, and the target of her gaze is fully visible. “I am together,” Damiel’s voiceover whispers as they kiss, uniting both the heavens and the Earth in a fleeting expression of devotion that stretches far beyond the transcendent, into the infinite.

Wings of Desire is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, can be rented or buy on Apple TV, or the Blu-ray or DVD can be bought on Amazon.