David Lean | 1hr 26min

The first time we encounter housewife Laura Jesson in the local railway tearoom of Brief Encounter, it is impossible to fathom the depths of her heartache. Her eyes are wide but uncfocused, concealing a complex mix of emotions from her endlessly chatty friend Dolly and the man sitting with them, Dr. Alec Harvey, who abruptly leaves to catch his train. The vague unease that hangs in the air cannot quite be pinpointed to any specific kind of sadness, though by the time the extended flashback which dominates most of the film leads us back to this moment, we are given the context to fully empathise with her. There wasn’t any way for us to know it before, but these are her last few minutes with the man she has secretly spent several weeks falling deeply in love with, and yet who can now only bid a final farewell with a discreet squeeze on her shoulder before disappearing forever.

In the absence of any giant romantic gesture or swooning kiss, this anticlimax brought about by Dolly’s unwelcome interruption is quietly shattering, forcing Laura to retreat into her mind and away from the onward march of an oblivious world. Time is a precious resource in Brief Encounter, particularly at the railway station where her and Alec’s schedules fleetingly align every Thursday where a giant clock imposes on their tiny figures, and through which the echoes of hours and minutes announce each new arrival.

In essence, this setting is an icon of persistent transience, bringing strangers together every day by a common need to travel before separating them the moment they board a train. The ticket inspector and tearoom owner whose small talk frequently diverts our attention perfectly typify this, teasing a potential romance which never has the time to grow into anything fruitful. Together, they also form a more innocent reflection of Laura and Alec’s covert affair, with all four love interests trying to explore relationships confined to a fleeting moment in time. The romance is intoxicating, but the demands of life never go away, consistently drawing Laura and Alec back to their families at home.

At least within her subjective recollections of the past, Laura is able to exert some control over the flow of time and carry pieces of it into the future. As she returns home and sits down with her husband Fred, she begins to confess her infidelity, though not aloud. Instead, her voiceover pours out what she might have said if the stability of their family unit wasn’t at stake. David Lean starts to leap back into the memories of her affair with Alec here, from their innocent first meeting in the tearoom, through their first kiss, and eventually to that final decision to part ways. Laura’s narration drips with sentimental lyricism, and yet equally infused with it is the heavy guilt that slowly erodes her dignity.

“It’s awfully easy to lie when you know that you’re trusted implicitly. So very easy, and so very degrading.”

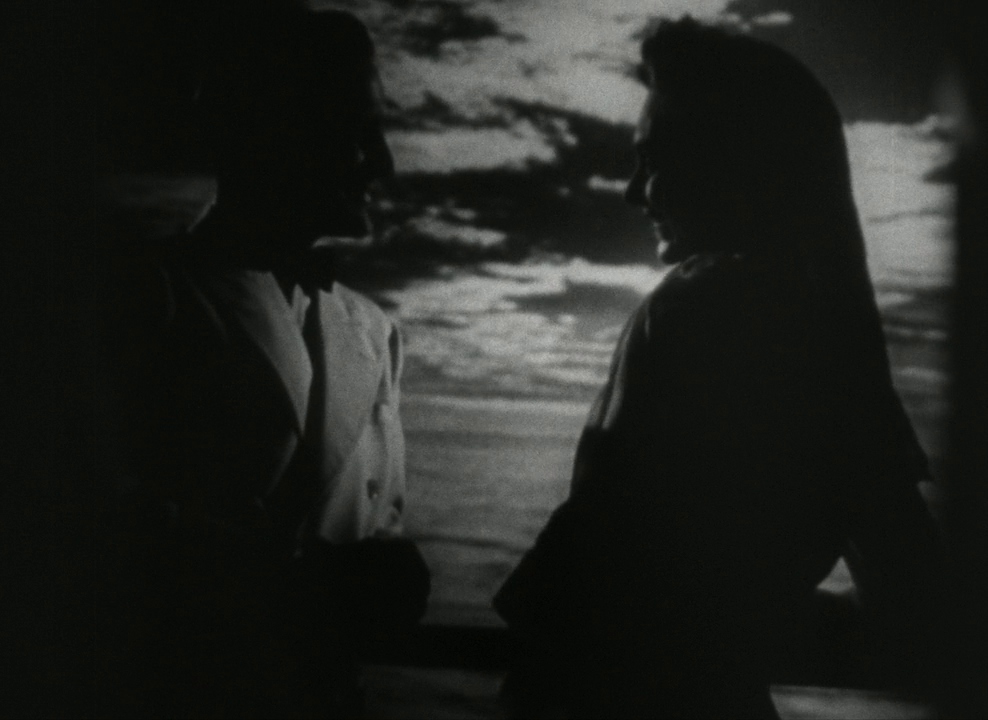

Love and shame are closely intertwined here, both being deeply internal emotions that cannot be openly expressed to the world, and which thus lead to greater repression. Lean’s elegant camera movements and deep focus capture this tension with immense aesthetic beauty, especially drawing on the poetic realism of French auteurs Jean Renoir and Marcel Carne which inevitably leads such romances to tragically fated ends. Clouds of smoke and shadow obscure scenes of blooming passion at the railway station, while the whistle and rattling of passing trains intermittently drown out speech altogether, absorbing Laura into a dreamy reverie that offers an escape from ordinary life. When her relationship with Alex progresses to the point of meeting up elsewhere, lush gardens and babbling rivers begin to host their secret dates, calling back to the nostalgic vacation of A Day in the Country. Meanwhile, the piano concertos of Sergei Rachmaninoff delicately climb and descend scales in romantic accompaniment, though never quite losing track of the sorrow shared between these guilty lovers.

That this is the same director who would later craft some of Britain’s greatest historical epics in The Bridge on the River Kwai and Lawrence of Arabia is somewhat surprising given the profound introspection of the piece, though if anything Lean is simply proving the versatility of his immense talent. His inspired development of characters may be the strongest similarity between these films, here seeing Laura shrivel into a guilt-ridden shadow of herself as she takes up smoking to calm her nerves, and quietly interprets an accident involving her son as the universe’s punishment.

Perhaps even stronger though are those moments which visualise Laura’s interiority, imagining an impossible future through double exposure effects which see her and Alec cruise, dance, and wander tropical beaches, and later hanging on her face as she tells Fred her first lie and ashamedly stares into a mirror. The deeper she sinks into her guilt, the darker Lean’s lighting becomes too, as a much greater deception further along sees her silhouetted at a payphone, with only the profile of her sweaty, anguished face vaguely illuminated.

Being shot right before the end of World War II in 1945, the hope for some restored order to the nuclear family unit looms large in Brief Encounter, and so there is no disagreement here between Laura and Alec when the shared guilt becomes insurmountable. A job opportunity for Alec in Johannesburg provides the perfect opportunity to make a clean break, but not before a quick journey back through all those locations that they had previously visited together.

For a short second after his train finally departs, a suicidal impulse crosses Laura’s mind. Lean’s camera tilts to the side in a dramatically canted angle as she rushes out to the platform, though panic quickly dissipates into mournful regret, and the rest of her life fades back into view. The dream ends, as does her internal confession, and although Fred has not heard a single word of it there is a quizzical look on his face. “You’ve been a long way away. Thank you for coming back to me,” he gently acknowledges with absolute sincerity. Perhaps Laura will may never find the resolution she seeks with Alec, or the same excitement which lifted her out of the monotony of being a 1940s housewife. But if there is any solace to be found, then it is in the love that is still very much present in this modest home, never even requiring such complex sentiments to be spoken aloud in order to be mutually understood.

Brief Encounter is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, is available to rent or buy on Apple TV, and the DVD or Blu-ray can be bought on Amazon.

Pingback: The 50 Best Cinematographers of All Time – Scene by Green