Roman Polanski | 2hr 5min

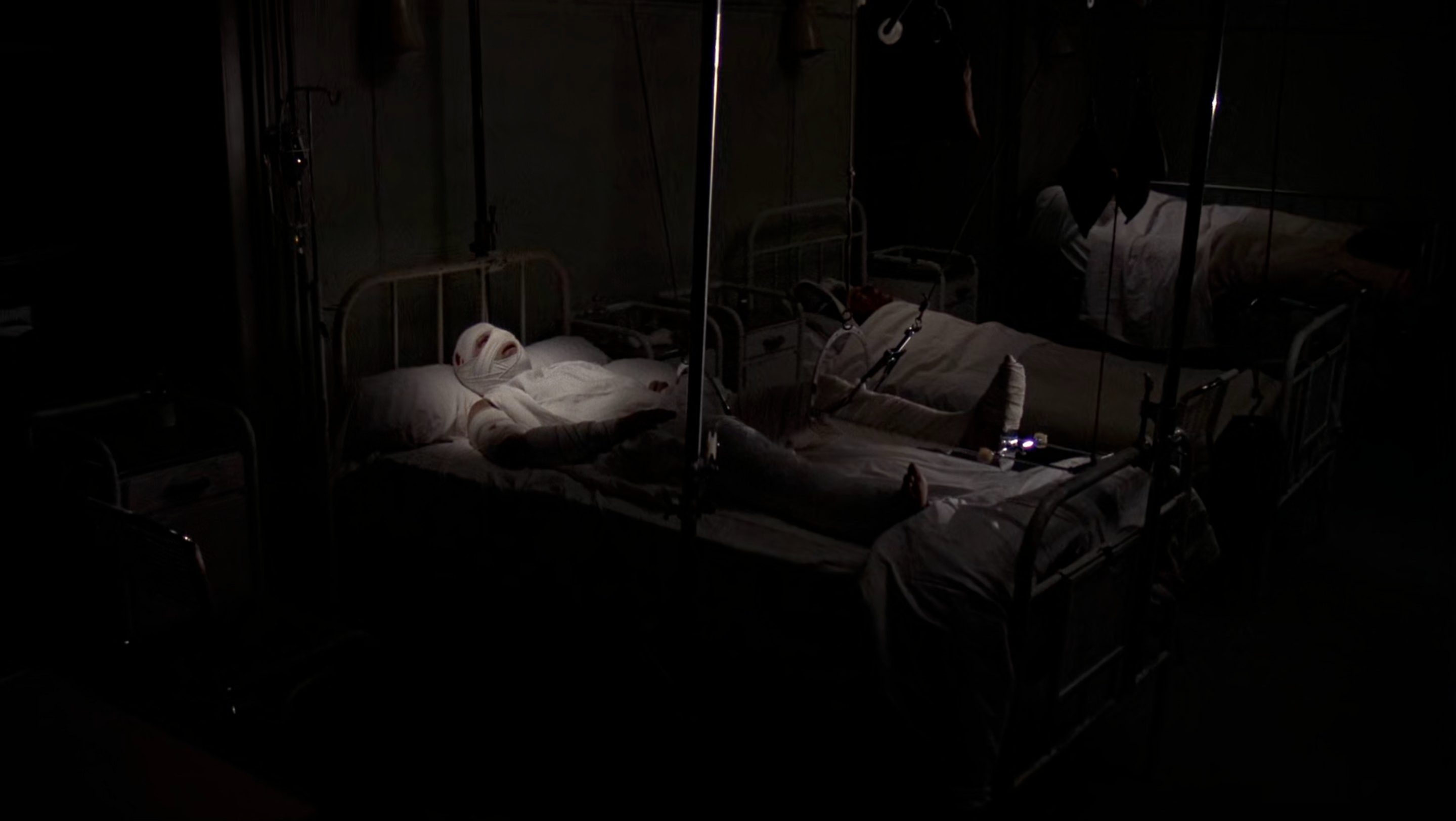

It is a horrifying enough realisation on its own that Polish immigrant Trelkovsky is slowly transforming into Simone, the previous occupant of his Parisian apartment who jumped from its window. Even more disturbing is the creeping feeling that his condescending neighbours are erasing all traces of his real identity, leaving the ambiguous question by the end of The Tenant as to whether it is even worth distinguishing between the two residents. From the moment he goes to visit a barely alive Simone in her hospital bed with her face wrapped in bandages, he feels strangely drawn to her, though he is abruptly interrupted from investigating further when she locks eyes with him and lets out a monstrous scream. Sometime later, she dies from her injuries, though one thing at least has been made clear – she too sensed the presence of that mysterious, frightening connection between them.

In the eyes of Monsieur Zy and the other inhabitants of their building, that bond is superficially obvious. Both the foreigner Trelkovsky and the queer-coded Simone are troublemakers with little regard for those social conventions that keep a tenuous peace – no loud noises, no visitors, fall in line with the majority opinion. They are as bad as that mother and her disabled daughter being viciously evicted from their apartment via a petition that Trelkovsky refuses to sign, which incidentally alienates him even further. The unifying thread binding him together with these similarly ostracised strangers is never explicitly labelled, but it doesn’t need to be. Whether one diverges from the mainstream through their sexuality, ethnicity, or physical condition, there is little room to be made for outsiders in these flats.

With a setting this absurdly oppressive, one could easily imagine some alternate version of The Tenant as a Kafkaesque comedy, or a drama aimed at confronting social issues. As the final piece of Roman Polanski’s Apartment trilogy though following Rosemary’s Baby and Repulsion, Trelkovsky’s disintegrating psyche is complete submerged in paranoid horror, creeping into those safe spaces one would hope to savour as their last sanctuary in a treacherous world.

Cinematographer Sven Nykvist strays far from his usual close-up heavy work with Ingmar Bergman here, using wide-angle lenses that claustrophobically warp the dimensions of building hallways around Trelkovsky, and tracking his camera through dark rooms with measured precision. The Hitchcockian influence is apparent too, mounting an intrusive suspense in the opening shot as we float outside the dreary grey establishment and peer through its windows, and later when the central stairwell is framed at dizzying angles that almost look to be straight out of Vertigo. Like James Stewart’s private detective Scottie, he too is destined for a great fall.

With an inquisitive Trelkovsky being pulled deeper into a mystery that won’t let him go, the comparisons don’t end there either. His observations of suspicious behaviours through binoculars frame him like Stewart in Rear Window, as he amasses a collection of bizarre clues pointing back to Simone in long, patient stretches of purely visual storytelling. So too does Psycho’s influence rear its head as her identity begins to take over, cutting a feminine silhouette of his body in the apartment that has steadily grown darker and messier over time, and which reverberates disarray across a wintery lakeside chaotically littered with fold-up chairs. Though Polanski often uses wide shots to frame his deteriorating mise-en-scène, his compositions frequently carry a psychologically invasive effect, isolating him at the centre of a conspiracy that follows him wherever he goes.

As for how much of this plot is merely in his head, Polanski consistently underscores Trelkovsky’s loose grip on reality, but otherwise remains purposefully ambiguous. “The former tenant always wore slippers after ten o’clock. It was always more comfortable for her – and for the neighbours,” he is first advised when he moves in, though what starts as simple pointers soon becomes a cloud of ridiculously strict expectations hanging over his head, making him anxious to even turn on a tap. Though lingering deep in the subtext, Polanski’s past as a Holocaust survivor and victim of prejudice after the war is embedded in Trelkovsky’s experiences with this community of authoritarian neighbours, and the allegory is only emphasised in his bold but ultimately misguided choice to cast himself as the lead. When he begins to realise the influence coming from servers at a local café trying to offer him Simone’s regular orders and cigarette brands, Polanski’s acting simply cannot sustain the intensity of his own direction.

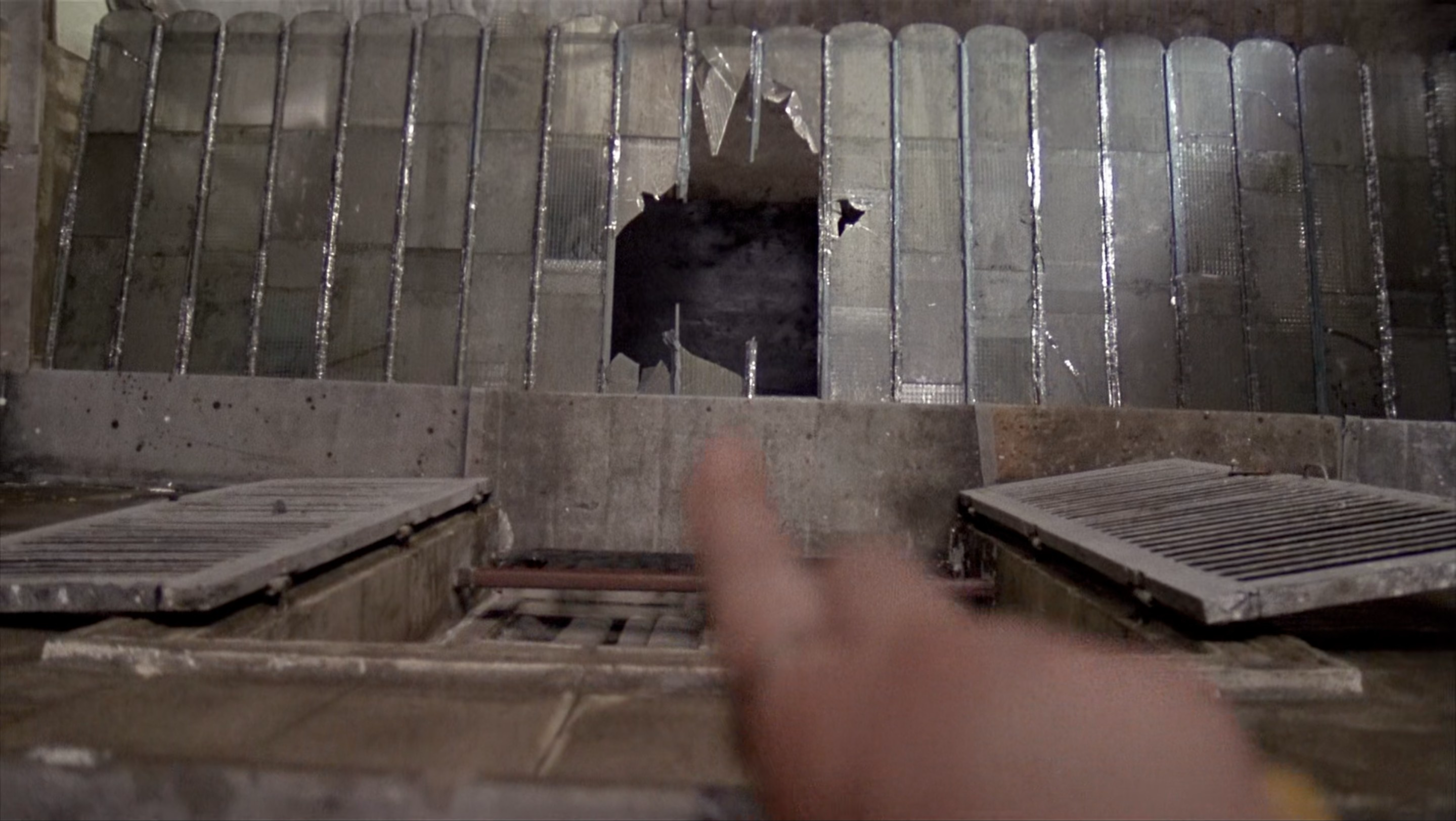

Still, this imperfect performance does not keep The Tenant from excelling in its psychosexual study of alienation and guilt, leading us along a string of bizarre motifs disassociating Trelkovsky from his physical body. When he finally investigates the bathroom where he has spied neighbours standing motionless for hours on end, he finds a wall of hieroglyphs, leading him back to Simone and her academic studies in Egyptology. Looking out the window, he sees another figure watching him through binoculars from the reverse angle – only to realise with horror that it is himself in his own apartment. An effectively unnerving score of trembling and plucked strings accompany these unearthly discoveries, many of which are never so much explained outright as they are weaved together into an occult of urban conformity and ostracisation, until that sacred sense of selfhood comes into question.

“At what precise moment does an individual stop being who he thinks he is?”

In the midst of his madness, this is the question Trelkovsky is driven to one drunken night as he feels himself slowly slipping away. “If you cut off my head – would I say, ‘Me and my head’ or ‘Me and my body’? What right has my head to call itself me?” he slurs to his new friend Stella – a woman who of course used to be Simone’s friend too. Like the Ship of Theseus that had all its original components replaced over time in the famous thought experiment, we too are left to question how long he can still call himself Trelkovsky while all those pieces that once defined him are being swapped out. In the end, he is only becoming what everyone else already sees him as – just another outsider, trying and failing to play by an impossible set of rules.

Of course, the more Trelkovsky tries to placate his neighbours’ demands, the more he loses control of his own mind, leaving us to wonder with this recent emergence of Simone is really the manifestation of a more authentic, transgressive self he has tried to repress for the sake of the status quo. His courtship with Stella often feels more like a social obligation than anything else, hinting at a part of his sexuality that he has never properly sought to understand, and which has only fuelled his fear of being exposed.

In effect, Trelkovsky is caught in a destructive loop of self-loathing, finally throwing himself out of his apartment window as Simone did before him, and then almost immediately repeating the act a second time. So too does Polanski recall the opening tracking shot at this moment as well, floating the camera around the outside of the building, but this time seeing Trelkovsky’s hallucination of all those who had conspired against him cheering and clapping his attempted suicide.

It isn’t until Trelkovsky finds himself waking up under layers of bandages that The Tenant finally comes full circle though. Now at his lowest point, he is more identical to Simone than ever, bearing a perfect resemblance to the maimed, faceless woman he met back in the hospital ward that he now occupies. As his eyes meet those of the visitor standing above him, all he can do is let out a monstrous scream – not just in recognition of his own face, naively peering down at his disfigured body, but also of that infinite loop which will once again take him down the same deranged path of stolen individuality and mutilated personhood.

The Tenant is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, is available to rent or buy on Apple TV, Google Play, or YouTube, and the Blu-ray or DVD can be bought on Amazon.

Pingback: An Inexhaustive Catalogue of Auteur Trilogies – Scene by Green