Andrei Tarkovsky | 1hr 48min

If one were to ask Andrei Tarkovsky, applying literal interpretations to his semi-autobiographical film Mirror is about as futile as discerning the past through rigorously objective methods. After all, factual history cannot possibly take any tangible form that may be touched, smelt, and tasted by future generations the same way it could for those who were there. The moment it disappears from the present, it no longer exists even in the minds of firsthand witnesses, who now filter it through their own subjective recollections. To then attempt a faithful reconstruction of its events through whatever form of media they deem most effective only separates our current understanding of the past further from whatever truth once existed.

This is no reason to give up entirely on such an endeavour though, Tarkovsky asserts, but rather to appreciate the reflection of our imperfect humanity that is found in such evocative illustrations. It is through his cinematic manipulation of time’s subjective flow that Mirror escapes the false impression of constructed reality, and instead becomes a portal into his pre-war childhood memories warped by the dreams, doubts, and desires that have emerged in the decades since. No decent film should be interpreted purely through a literal lens, but Mirror least of all ought to be taken as such, lest one finds themselves misguidedly rejecting Tarkovsky’s profoundly spiritual meditation on family, nostalgia, and humanity’s flawed consciousness.

It quickly becomes apparent that the first-person perspective taken by Tarkovsky is a surrogate for his own, as we realise our protagonist Alexei is never quite visible in the post-war timeline. He is the source from which these memories spring forth, his face always sitting just outside the frame while he commands the non-linear narrative with pensive voiceovers and conversations, and only ever appearing onscreen as a child in the story’s pre-war timeline. That he seems to be recalling the past as an out-of-body experience is the first clue that these flashbacks aren’t quite accurate renderings, but as Tarkovsky sinks us deeper into Alexei’s pool of dreams, we come to recognise it as the mirror upon which this unseen man’s life is reflected and distorted.

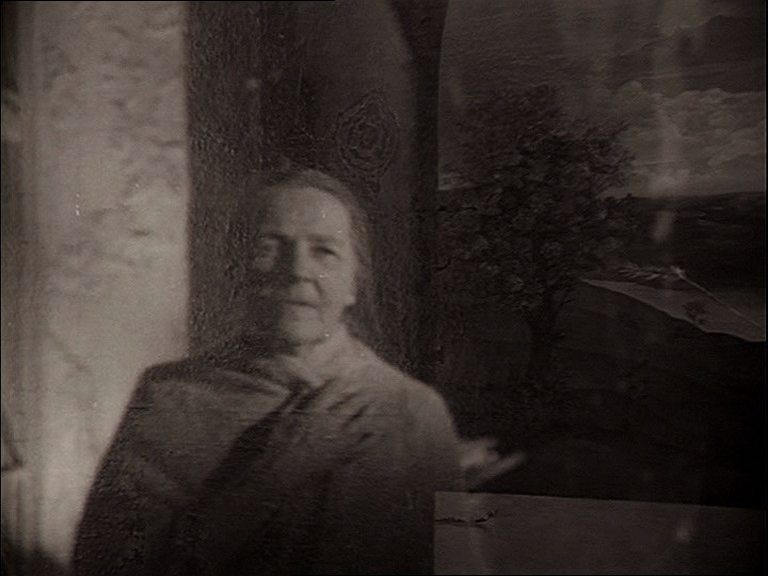

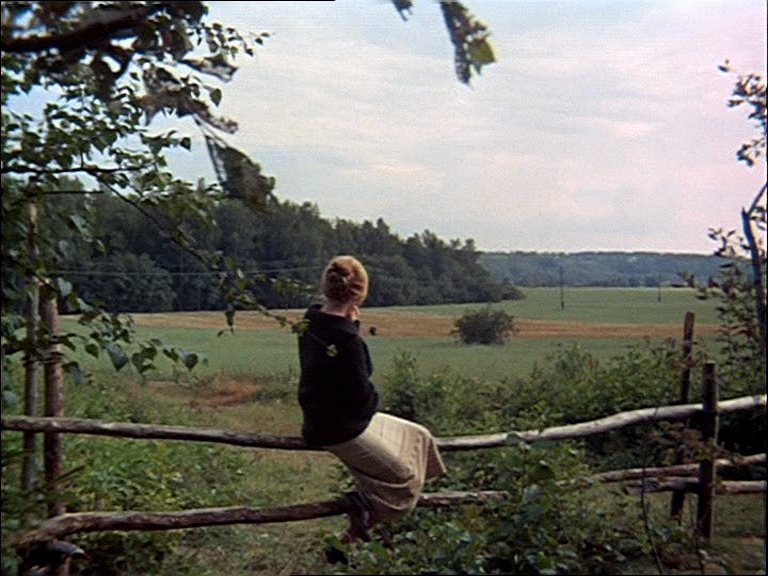

It is revealing too that the figure who looms largest here is his mother. Being named Maria after Tarkovsky’s real-life mother, and thus drawing parallels to the Blessed Virgin Mary, she becomes an icon of sacred veneration in Mirror, yet also a woman with a vividly complex life just beyond the periphery of Alexei’s view. In our first meeting with her, Tarkovsky even painstakingly recreates an authentic photograph of the real Maria sitting on a roughly erected fence of sticks, gazing towards the green fields beyond her home as if expectantly waiting for an important arrival. With her face totally hidden, she seems to exist in a world inaccessible to the young Alexei, her thoughts preoccupied by ideas and emotions beyond his naïve understanding. Still, the camera pushes forwards past rustling branches and into her orbit, where we can finally see what she sees – a man approaching from the distance.

He is not her husband, we discover, but rather a passing doctor who carries a warmer demeanour than Alexei’s actual father, and who on this day happens to be walking the same path. In the grand scheme of Alexei’s childhood, this man holds very little significance, and yet it is notable that this memory stands out in the absence of the family patriarch. Though his appearances are rare, the void he leaves behind is often filled with the poetry of Tarkovsky’s own father, Arseny Tarkovsky, standing in for a traditional film score.

With evocations of Greek tragedy, physical death, and spiritual transcendence emerging from one poem ‘Eurydice’, new impressions are drawn from Maria’s reluctant slaughter of a cockerel at her neighbour’s house and her guilty departure. Though the scene eventually comes to an end, the poetry continues its gentle contemplations through black-and-white, slow-motion imagery of a mighty wind running through dense vegetation, rolling a brass ornament off a small wooden table, and billowing through translucent white drapes hung in Alexei’s home. Whether expressed in spoken word or moving image, the romantic abstractions of both father and son run strong, and merge to create a cinematic lyricism.

“I dream of a different soul dressed in different garb,

burning up like alcohol as it flits from timidity to hope,

slipping away, shadowless,

leaving behind lilacs as a memento on the table.

Run, my child, and mourn not for poor Eurydice,

but drive your copper hoop through the wide world,

while in response to every step, you hear the earth reply, its voice joyful and dry.”

An excerpt from ‘Eurydice’ by Arseny Tarkovsky

Though Arseny Tarkovsky’s words encourage his son to move on from the lost love of Eurydice, the actual struggle is far more burdensome with the weight of memory holding him down. Does the mythological figure of Orpheus’ deceased wife stand in for Alexei’s childhood, his ex-wife Natalia, or perhaps even his mother? Andrei Tarkovsky would never claim such a direct correlation, though given his Oedipal casting of Margarita Terekhova as both Maria and Natalia, the two women are tied very strongly to Greek legend. Where they split is in their characterisations – where Maria embodies divine grace, Natalia is cold and cynical, suggesting a spiritual corruption that has degraded with time.

At least, this is how Alexei perceives them, and Tarkovsky is fully aware that he is far from a reliable narrator. It is more than likely that Maria never had the face he recalls now, instead letting her take the appearance of the other most significant woman in his life, and when Alexei even admits this to Natalia he also expresses a slight suspicion of why this is the case.

“I pity you both, you and her.”

He is not alone in seeing these echoes across past and present either, as the double casting of both a young Alexei and his son, Ignat, reflects the patriarchal side of the Oedipus allegory that Natalia bears witness to. Just as Alexei’s father grew distant from his son, so too is Alexei failing to connect with Ignat, who Natalia notes in horror “is becoming like you.”

Tarkovsky does not seek so much to explain these repeated generational patterns though as he wishes to capture the raw essence of time as it passes through them, cycling in rhythms that may be more richly experienced from outside history’s traditionally linear progression, and beyond the limits of conscious thought. As Tarkovsky intercuts Alexei’s reluctant rifle training during World War II with archival footage of Soviet battles, time is compressed into a single point that weighs on the young boy’s mind. Meanwhile, those long, slow camera movements which gently drift through uninhabited rooms stretch it out into eternity, offering a retreat into the soothing reverie of his frozen dreams.

Perhaps the greatest manifestation of time’s transient passage though is in Tarkovsky’s observation of nature’s effervescent, primordial elements, moving independently of any human influence. As if brought to life by some invisible creator, a gust of wind sends a single rippling wave through a field of long grass while Alexei’s neighbour walks away, and the frequent emphasis on grass, snow, dirt, mud, and stone on the ground imbues Tarkovsky’s mise-en-scène with distinctly earthy textures. Even the setting of this cottage on the edge of a forest suggests an ominous tranquillity, framing Alexei’s childhood as a fairy tale where things that were once deemed impossible manifest with ethereal wonder.

Somewhat paradoxically, fire and water frequently co-exist in the same spaces throughout Mirror too, creating a subtly incongruent dreamscape where candles light the room of Maria’s self-baptism, while rain simultaneously trickles in from cracks in the ceiling. The water which consecrates her as a divine entity in Alexei’s mind is the same which eventually caves in the room’s ceiling, wielding an equally immense power over life and death.

Elsewhere, Tarkovsky’s floating camera pauses on a dirtied mirror reflecting the burning of Alexei’s family barn, but as it turns around and directly approaches the disaster, we note the quiet patter of rain dripping from the wooden roof. Like the grand final set piece of Tarkovsky’s later film The Sacrifice, this fiery structure becomes a theological icon of divine destruction in stark contrast to the nourishing waters of life. On an even more fundamental level though, he is composing a surreal image of primal elemental power that we, like the characters, are simply forced to gaze at in helpless awe.

From within the fragile bubble of Alexei’s dreams, we can easily see why he pities those like Natalia who claim to have never witnessed a true Old Testament miracle. For Alexei, such miracles are impossible to escape. One strange visitor disappears mid-scene, leaving no trace of their existence besides the condensation of their absent teacup, and in what may be the defining shot of Tarkovsky’s filmography Maria levitates several feet above her bed, draped in white bedsheets. “Here I am, borne aloft,” she tenderly whispers to Alexei, becoming an angelic image of maternal transcendence in the eyes of her child.

As much as sequences such as these feel like a total departure from reality, their roots in mid-century Soviet Union history remain incredibly relevant. We see them not just in the grainy newsreels of the Spanish Civil War, nuclear explosions, and the launch of a USSR balloon that tangentially connects Alexei to a broader cultural context, but Tarkovsky even takes the time to examine a portion of Maria’s life working in a printing press for propaganda under Stalin’s totalitarian rule. Her fear that she may be responsible for a misprint is understandable when considering the consequences of such an error in this oppressive era, which may see her accused of treason. Though the young Alexei is absent from these scenes, touches of an almost imperceptible slow-motion continue to suggest that they are similarly being lifted from outside their original time frame – perhaps some attempt from an older Alexei to reconstruct an alternate image of his mother through second-hand stories.

It is not uncommon for hazy memories such as these to come flooding back when one reaches the end of their mortal life, though Tarkovsky suggests that Mirror is in fact depicting the complete inverse of this. Alexei is not revisiting his past because he is dying, but as the doctor mysteriously hints after his death, he rather wasted away due to his heavy conscience. Tarkovsky’s pain can be felt acutely here, trying to resolve his guilt over perpetuating those cycles of distant fathers and overburdened mothers that were ingrained in him as a child. Even as the mysteries of the human mind continue to elude us throughout Mirror, his precise control over the raw elements of time, memory, and life keep sinking us further into its surreal depths, not so much crafting an artefact of absolute historical truth than revelling in the extraordinary impossibility of such a task.

Mirror is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, can be bought or rented on Apple TV, or you can buy the Blu-ray on Amazon.

Pingback: The 100 Best Shot Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Directors of All Time – Scene by Green