Ridley Scott | 2hr 38min

The task of cinematically adapting a historical legacy as immense as Napoleon Bonaparte’s is not one to be taken lightly, especially when densely packing a feature film with several decades’ worth of his conquests. Although Ridley Scott’s interpretation of the French leader’s life covers an enormous span of time from the French Revolution to his eventual exile, it does not carry the same dramatic weight as Abel Gance’s more focused 1927 epic, which ends its story much earlier with Napoleon’s grand triumph at 1796’s Battle of Montenotte. A great deal of room is allowed there for the sort of historical detail which Scott merely skims over in title cards announcing new characters, events, and years – and even with a shorter length on his side, his Napoleon rarely carries the same vigorous energy as its five-and-a-half-hour counterpart.

To be fair, this comparison to one of France’s most celebrated cinematic masterpieces does not give Scott credit where it is due, and only serves to emphasise how thinly he spreads this story across a vast scope. The strength of his direction here lies not so much in its loosely sprawling structure as it does in the humour, blocking, and spectacle of individual moments, offsetting Napoleon’s legacy as a military commander and tactical genius with scenes of his childish petulance. The sense of divine purpose which imbues him with regal confidence is the same which drives him into entitled tantrums at the dinner table, as he amusingly proclaims that “Destiny has brought me this lamb chop!” with an absurd lack of self-awareness.

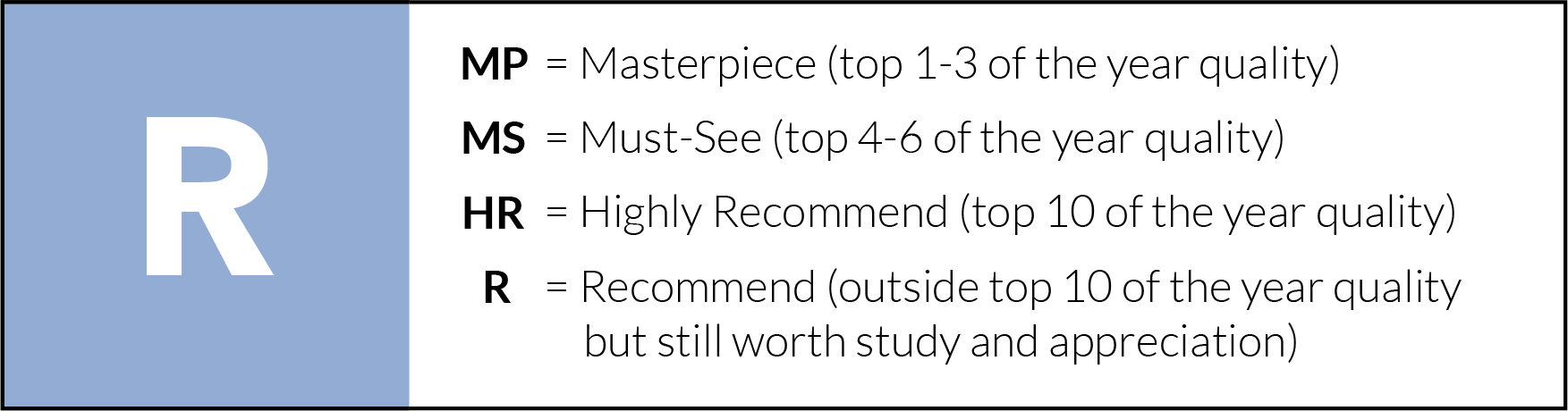

Scott does not go so far as to probe the psychosexual depths of Napoleon’s emotionally stunted nature, though his inability to connect intimately with others is all too apparent, especially when his wife Joséphine enters the picture. Their sex is profoundly dispassionate at first, though an awkward intimacy soon develops which only further underscores his strange infantilism. Tied in with that as well is an egotistic dependence on her admiration, forcing her to declare that he is the most important thing in the world, and conversely seeing him admit with far greater truth that he is nothing without her. After all, he needs an heir to carry on his legacy, and the prospect that he may be infertile threatens the foundations of his entire reign.

Perhaps this is why Joaquin Phoenix slips so naturally into this eccentric vision of the French emperor, despite being much older than Napoleon actually was at the height of his power. This is not a young, virile man with boundless charisma and masculine poise, but a cagey strategist who cannot translate his sharp mind on the battlefield to his own personal life. This is not the Napoleon that history remembers, and given the accusations of historical inaccuracy that Scott has brushed off with disregard, it may not even be the Napoleon that existed. Creative licence is a powerful tool in the right hands though, and the line that Scott draws between male leadership, ego, and impotence is vivid, demonstrating that the insecure fool and the impressive military leader are not mutually exclusive identities.

After all, when it comes to the latter Scott relishes shooting Phoenix’s Napoleon against backdrops of remarkable spectacle, starting with Marie Antoinette’s execution at the Place de la Révolution in front of riled-up masses, and later seeing him win extravagant battles in Austria, Russia, and Egypt. The siege of Toulon is his first great success as an artillery commander, and also Scott’s first real demonstration in Napoleon that his deft control over giant set pieces has not faded over the years, borrowing a few visual and editing cues from D.W. Griffith as soldiers scale colossal walls and fires light up the night.

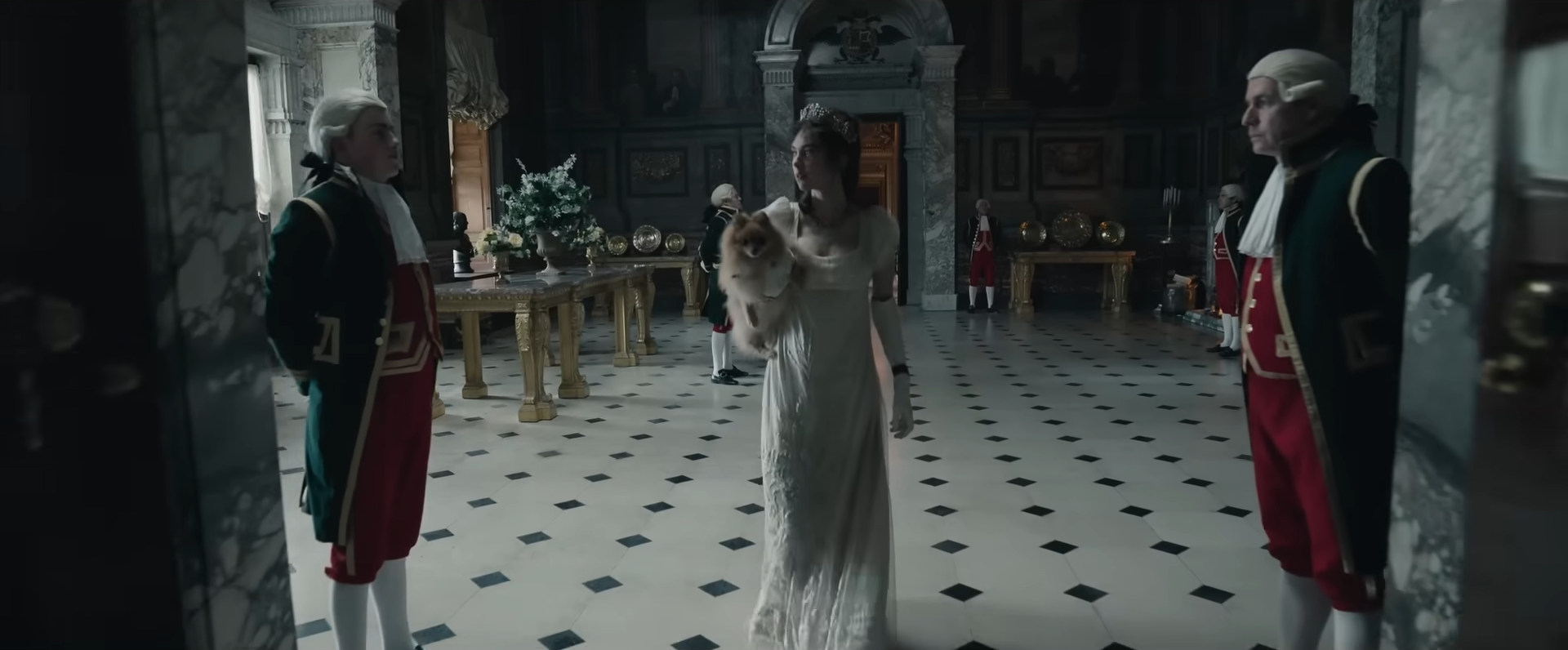

It is no coincidence that the detail of Napoleon’s tactical manoeuvring directly correlates to the brilliance of Scott’s technical direction either, as both reach their peaks upon the frozen wastelands where the Battle of Austerlitz unfolds. Using its natural geography of hills, trees, plains, and fog to his advantage, Napoleon lures the united Austrian and Russian forces into an ambush, drives them to retreat over a frozen lake, and shatters the ice with cannonballs, thereby winning one of the most significant battles of the Napoleonic Wars. Scott’s visual storytelling is remarkable here, coordinating complex interactions between enormous numbers of extras through hostile landscapes, and intercutting the action with visceral underwater shots of drowning, bleeding soldiers desperately fumbling to escape their fate.

Elsewhere, Scott imbues scenes with a dramatic weight in his slow-motion photography, and curates handsomely muted colour palettes with soft blue filters and the dim, golden lighting of candles. Napoleon’s greatest weakness though is its unevenness, inconsistently letting these soaring visuals come and go, and eventually dropping the focus on the French emperor’s personal life as the Battle of Waterloo approaches. In place of his emotional immaturity, an even greater form of egomania becomes apparent, seeing him boldly charge into combat with blazing confidence before witnessing the demise of his entire life’s work. For once, it is the opposing side that Scott captures with noble admiration, watching the Duke of Wellington’s army form infantry squares in rigorous uniformity and take the higher ground over Napoleon’s men.

Even with everything lost though, this is a man who will still carve out his own version of history. Was it the Russians who burnt Moscow to spoil the French victory, or was it part of Napoleon’s plan all along? Was it really his fault that he lost the Battle of Waterloo, or was it his incompetent marshals? Is the image of a mighty leader and master strategist really all there is to the first emperor of France? Scott does not so much seek truth in that matter as he uses it to underscore a modern scepticism towards our male leaders, and especially those whose meagre wisdom and childish convictions are undeserving of such enormous egos. If only this film was a little more refined in its focus, then perhaps he might have reconciled these distinct features into one character with greater formal acuity, backing up his technical brilliance with the sense of purpose that Napoleon himself was so blinded by.

Napoleon is currently playing in theatres.

Pingback: 2024 Oscar Predictions and Snubs – Scene by Green

Did you see Napoleon: Director’s Cut? I think like 45 minutes were added.

I have not, is it worth it?

Not yet. But I heard it is better and more cohesive.

Pingback: The 25 Best Female Actors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green