Michael Haneke | 1hr 49min

There is a perverse ritualism to the physical and psychological torture that strangers Paul and Peter exact on the Schober family in Funny Games. Personal motivations appear to be non-existent, and Michael Haneke even mocks the idea that some tragic backstory might explain their desensitised hostility. Truth is, there is no satisfying justification for the events that unfold over what was supposed to be the first night of the Schobers’ vacation at their lakeside getaway. Paul and Peter are completely void of any individuality, and rather serve a purely functionary purpose in Haneke’s disturbing piece of metafiction. They are simply acting on behalf of another invisible presence that exists just outside the boundaries of this story – us, the audience.

Within this self-aware framing device, it stands to reason then that Georg, Anna, their son Georgi, and their dog Rolfi are the sacrifices, satiating our desire for gratuitous entertainment. They too lack any specific backstories which might define them as individuals worth our sympathy, and yet when faced with Paul and Peter’s sadistic games, we naturally hope that these archetypal victims might triumph over their adversaries.

Still, Haneke knows us better than that. This family’s torture is the reason we are watching to begin with. We don’t care about them as human beings with rich, interesting lives. When the movie is over, we will immediately forget about them and move onto another set of characters whose trauma will entertain us for another two hours. We don’t have any right to complain when we see Paul and Peter brutally pick off each victim one by one. Isn’t that what we came for?

As such, the invitation that Funny Games offers into an entertaining story of visceral sensationalism unexpectedly turns the mirror back on us. In its reflection, we don’t just see ourselves, but an entire culture that thrives on the suffering of others, blurring the lines between fiction and reality until the distinction barely matters anymore.

When it comes to Haneke’s actual depictions of the film’s brutality though, it is surprising just how much he holds back from explicitly displaying it onscreen, and how much more gut-wrenching it is as a result. What we are left with is violence minus the thrill factor, hearing the snap of a leg breaking as it is hit with a golf club, or a gunshot go off in the living room while Paul nonchalantly fetches food from the fridge, leaving us to desperately wonder which of our main characters has been killed.

In truly torturous fashion, it is of course the most innocent who are offed first, with Paul leading Anna to Rolfi’s body in a cruel game of ‘Hot and Cold’, and Georgie suffering the fatal consequences of Peter’s random selection. On a broader level though, the dehumanisation of these characters has been in motion from the very start, with Haneke’s camera largely averting its gaze their faces, or otherwise refusing to budge from long, static shots that resist any emotional engagement. At its most devastating, his camera spends ten minutes painfully hanging on the immediate aftermath of Georgie’s death, though the image is composed in such a way that it takes a few seconds to notice his body on the floor, his blood splattered on the wall, and his parents paralysed with catatonic grief. Where so many other directors would draw out a visceral horror here, Haneke rather underscores its inert dread, and the chilling mundanity which begins to emerge in the absence of any cuts or action that might move the story along.

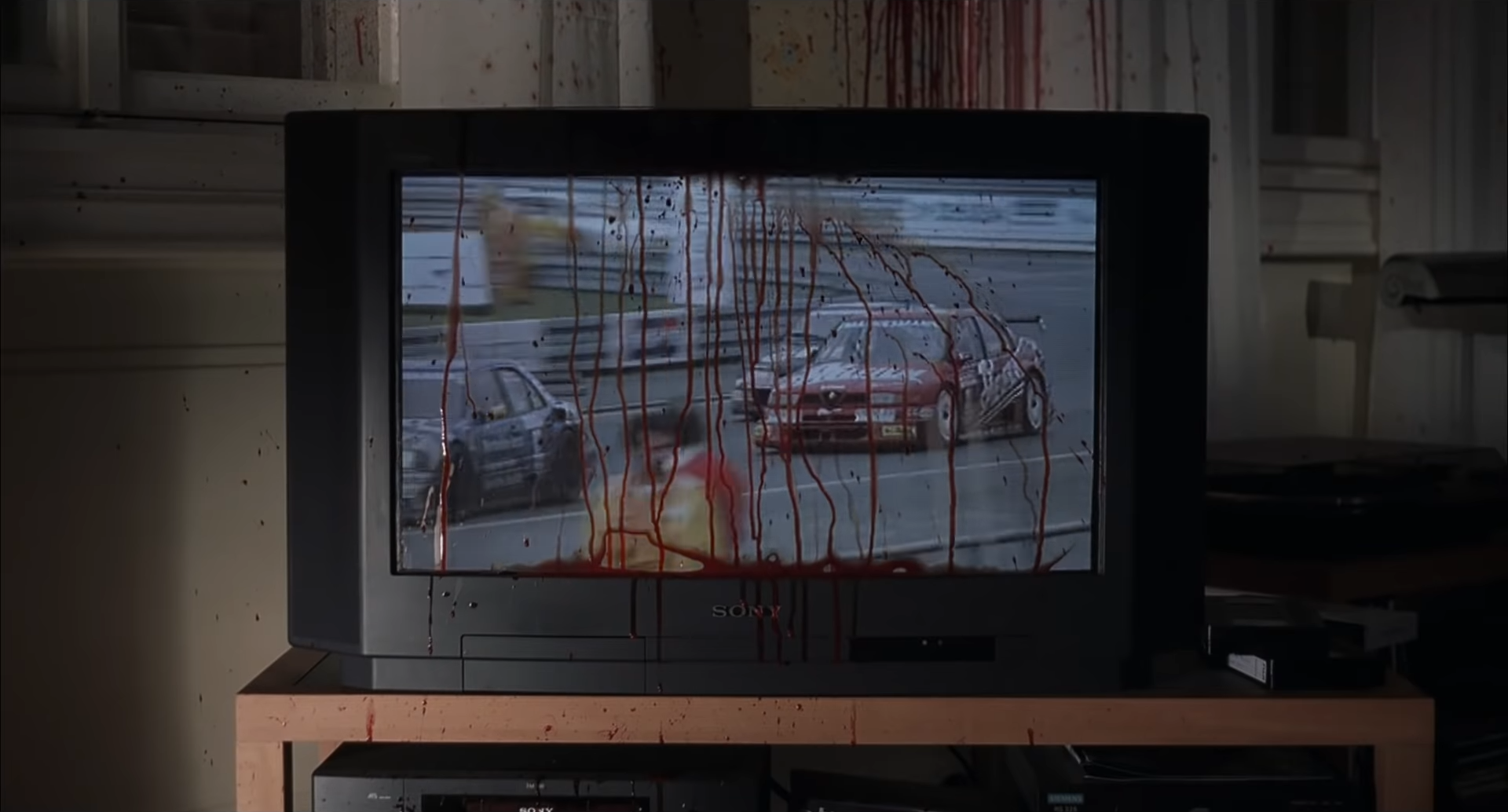

This is the state of gratuitous modern entertainment, Haneke posits, dissolving the lines between fiction and reality which we might otherwise use to justify our depraved tastes. There is absolutely no urgency on Paul and Peter’s part to put the family out their misery, and so as they sit down in front of the television and flick through an explosive action movie, a natural disaster news report, and a motor sports program, he reveals a common thread of suffering between them from which we draw the same indulgent gratification. Later when he sits on a close-up of the TV streaked with Georgie’s blood, the visual symbolism is even harder to ignore – modern mass entertainment has been thoroughly stained by its own sadistic corruption.

This is the icy, emotionless distance that Haneke would make a key feature in so many of his films from this point on as well, but never again with the dark satirical humour he carries in Funny Games. Though we certainly feel for these victims, the insecurity we feel is just as anxiety-inducing whenever Paul turns towards the camera and includes us in his fourth wall breaks. When he initially lays out the stakes and bets that the whole family will be dead in exactly 12 hours, we too are offered stakes in the wager that we subconsciously make every time we watch a horror movie.

“What do you think? You think they stand a chance? You’re on their side, aren’t you? Who are you betting on?”

When Georg begs for them to be put out of their misery, they again slyly implicate us in their rejection – “We’d all be deprived of our pleasure” – and when Anna claims they have suffered enough about 95 minutes in, they claim “We’re not up to feature-film length yet,” before turning straight to the camera and asking if we agree.

“Is that enough? You want a real ending, with plausible plot development, right?”

Haneke’s use of Paul and Peter as storytellers within the story is calculated, having them knock the house’s phone into water early on to cut off the family’s communication, and continuing to progress the film through their self-aware actions. Haneke isn’t afraid to let Funny Games stray from traditional narrative conventions whenever he wishes to prove a point about their fickleness though, granting our unrealistic wish that these villains would leave the family alone by letting them randomly disappear for some time, and consequently revealing how little tension there is in the absence of their violence. Similarly, the common objectification of female characters rears its head when the young men force Anna to strip. By hanging the camera on a close-up of her distraught face though, Haneke excises whatever perverse thrill viewers might have found, leaving us only with a deep discomfort.

If it isn’t clear yet just how much Haneke is playing with our hopes for a happy ending, then the all-powerful, invisible hand that has been guiding this family towards their inevitable deaths is certainly at least revealed when he blatantly throws all plot logic out the window to avoid an easy win for protagonists. It looks as if Anna’s quick thinking has saved the day when she grabs a rifle and blasts Peter away, allowing us a moment to cheer for what is the first death explicitly depicted onscreen, and the gory comeuppance we have been waiting for. If we are to find ourselves carried away in the triumph though, then there is one key detail we are likely forgetting – Paul and Peter are the storytellers, and they have the freedom to break whatever rules they like.

It only takes Paul a quick rewind on the TV remote to take us back a few minutes before his friend’s death, allowing him to take the rifle away before Anna can snatch it and thereby transcending the arbitrary narrative logic that we have falsely believed must apply to him as well. Suddenly, it becomes bleedingly apparent that we were never in control of this story, or any story that we consume for that matter. Storytellers might be there to serve their audiences, but they are the ones who have the final say, often making decisions simply based on their own erratic whims.

Still, Haneke delights in leading us on just a little bit longer in the final minutes of Funny Games, reminding us of a knife from the start of the film that was dropped to the bottom of the yacht Anna is now tied up in. Of course though, Peter is sure to snatch away the Chekhov’s Gun before she can free herself. After dumping her into the lake, it doesn’t bother Paul too much that they have prematurely killed their last victim an hour before the deadline they promised us. It’s hard work sailing, and it’s about time they grab something to eat – narrative convention be damned. There were many families before this one who have suffered their ritualistic torture, Haneke suggests, and there will be many more to follow. As long as it keeps us gratuitously entertained, then who are we to complain?

Funny Games is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel, or you can buy the Blu-ray on Amazon.