Andrei Tarkovsky | 1hr 29min

The line of influence between Andrei Tarkovsky and Ingmar Bergman is an intricate one, both being European filmmakers from the late twentieth century who were equally inspired by each other’s artistry, and in turn expanded the world’s understanding of cinema as an artform. It is hard to argue with Bergman’s assessment of the Soviet director as a master “who invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream,” though perhaps the greatest praise of all comes from Tarkovsky in the form of The Sacrifice.

The concerns of faith, atonement, and material reward in this modern parable could have belonged in a film written by either man, positioning us right on the edge of a potential nuclear holocaust that may destroy everything our protagonist Alexander holds dear. Still, in Tarkovsky’s collaboration with Bergman’s frequent actor Erland Josephson, his cinematographer Sven Nykvist, and production designer Anna Asp, he is clearly curating an aesthetic and tone that bears similarities to the Swedish director’s austere style. On top of that, The Sacrifice’s barren landscapes feature the stony coastlines of Gotland, a neighbouring island to Fårö where Bergman had lived and shot many of his own films since the 1960s.

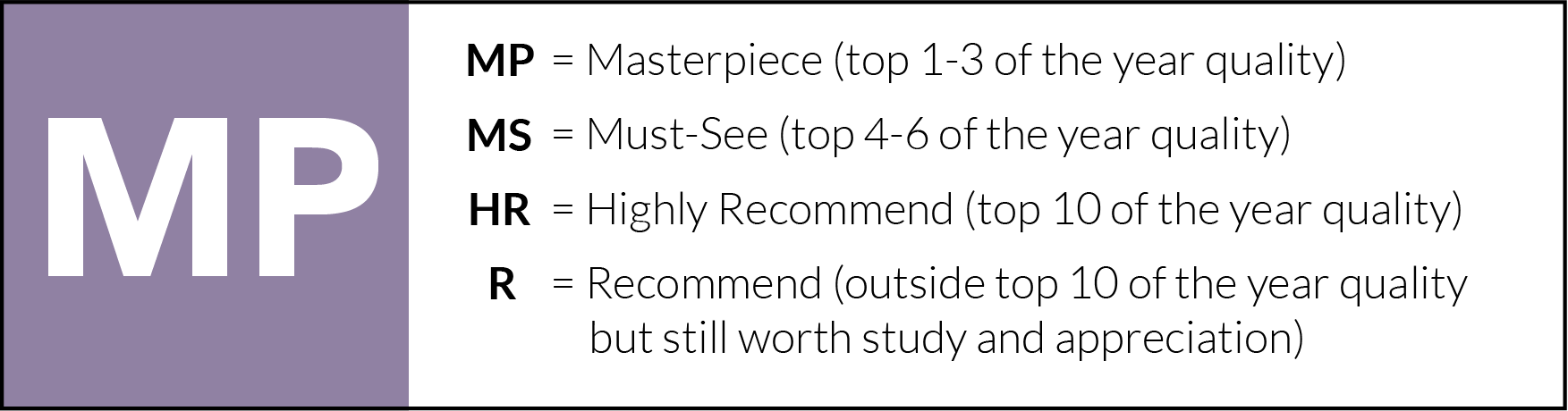

Even within the very first shot, Tarkovsky is paying reverent homage to Bergman through the lonely, withered tree that overlooks the Baltic Sea, referencing the solemn imagery of The Virgin Spring as an illustration of life persevering in sterile environments. Where such a tree became part of a violent, pagan ritual in Bergman’s film though, Tarkovsky holds onto it as an icon of Christian hope. As Alexander plants it in the soil with his mute son Little Man, he relays the fable of a monk who would climb a mountain every day to water a dead tree until it blossomed back to life. Through simple faith in a methodical ritualism, Alexander believes, life can be saved from the precipice of death, and rewards may be reaped. Despite all this, he also claims to have no personal relationship with God, only finding salvation from a “defective” civilisation in his small, pragmatic actions that exact change in his environment.

Much of Alexander’s complex characterisation could be just as easily found in a Bergman film, though where the distinctness of Tarkovsky’s style begins to emerge is in the meditative pacing stretching out through this long shot. Between the two, only Tarkovsky would have been willing to play out Alexander’s philosophical discussion with Otto the postman in a single ten-minute take that refuses to push into any close-ups, choosing instead to slowly dolly the camera with them from a distance as they slowly walk inland.

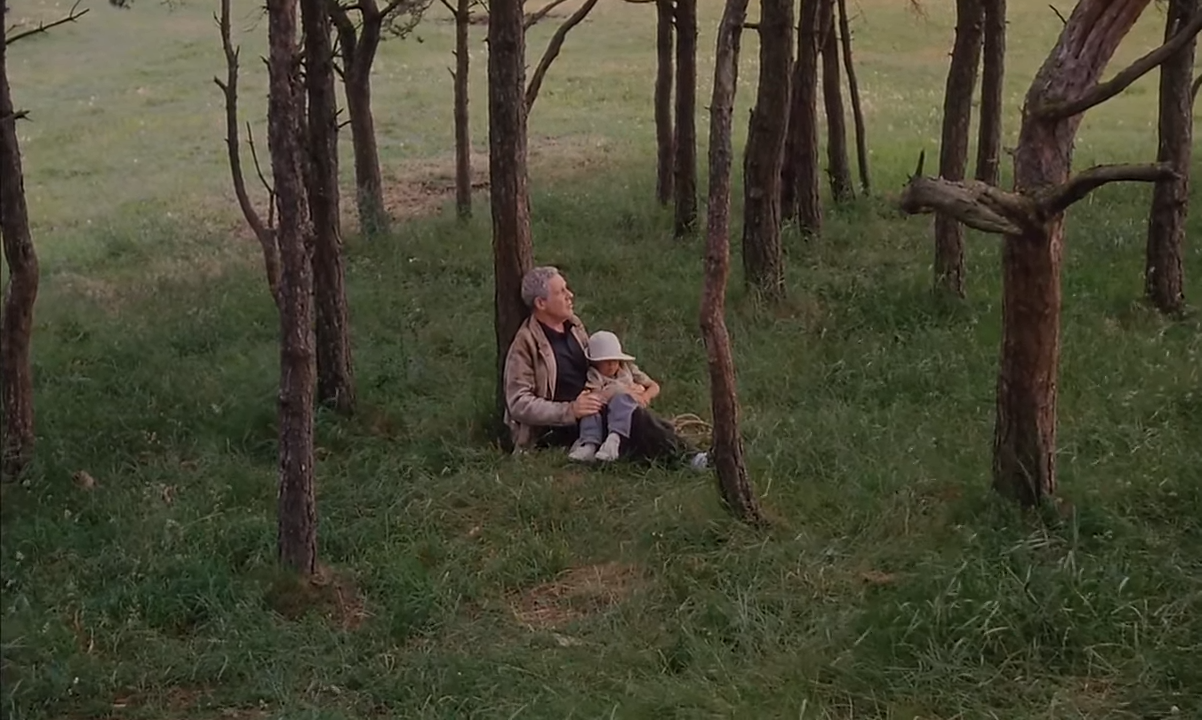

It is in this minimalist aesthetic that he subtly underscores the rich symbolic details of his scenery, especially once we reach the seaside house where Alexander lives with his wife Adelaide. It is his birthday, and a small group of friends have come bearing presents, one of which is a seventeenth-century map of Europe. “Every gift involves a sacrifice. If not, what kind of gift would it be?” Otto enigmatically foreshadows, perhaps planting the thought of spiritual offering in Alexander’s mind. Later when low-flying jets pass over the house and shake its foundations, Tarkovsky’s camera does not pay attention to his characters, but rather holds on a cabinet of glassware. The vibrations gradually increase from a gentle rattle to a violent shudder, before toppling a precariously balanced jug of milk off the shelf, shattering it into pieces, and spilling its liquid contents of maternal nourishment across the floor.

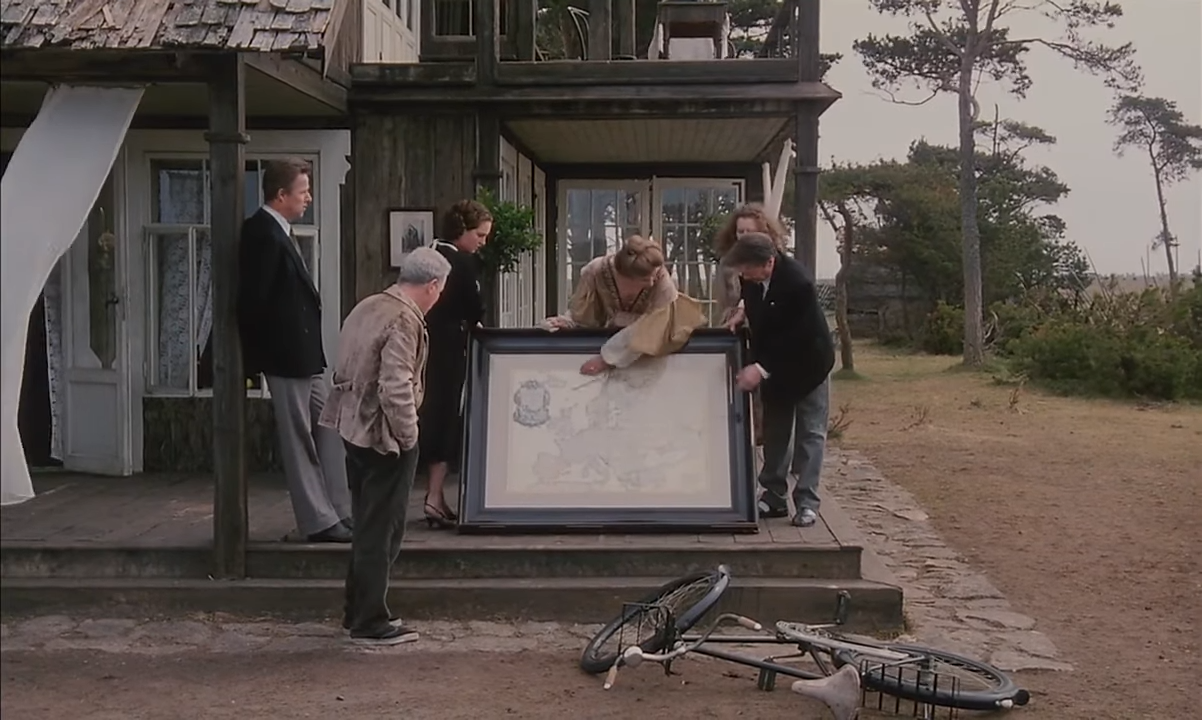

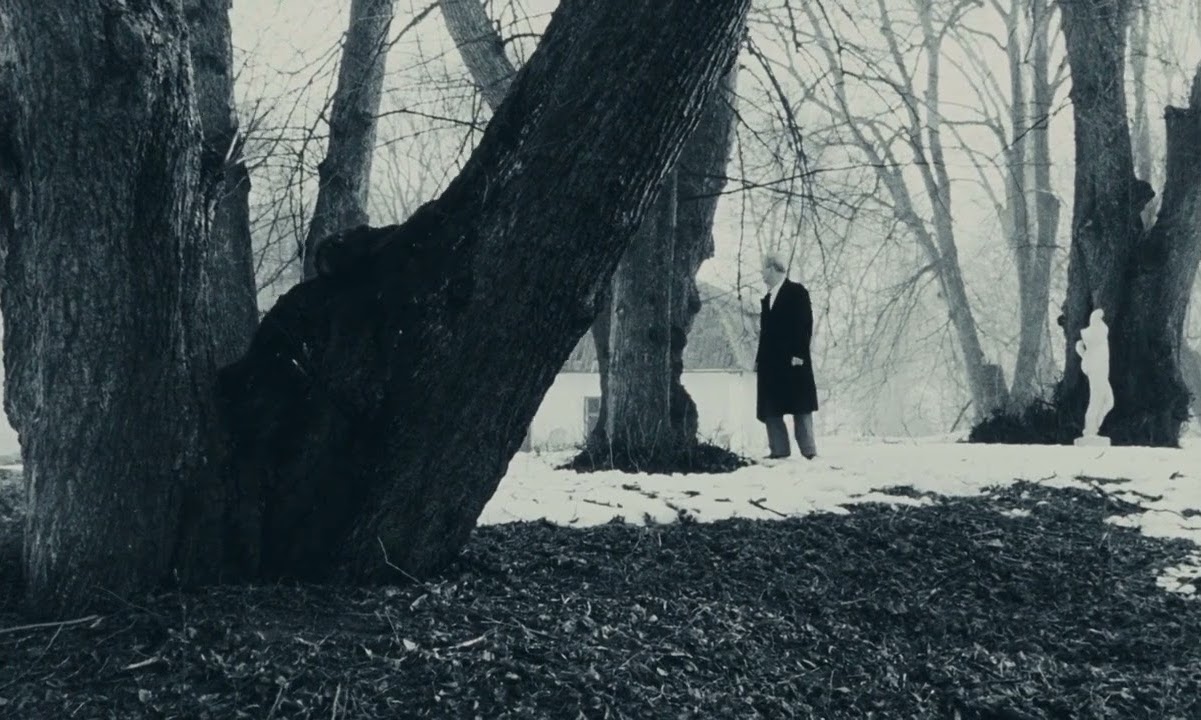

Not one to encourage such explicit readings of his iconography though, Tarkovsky often strives to separate his sensual, dreamlike imagery from clear-cut interpretations, much preferring instead to hypnotise us into an impressionable state that frees us from the constraints of traditional plotting. Each shot thus delivers its own story of ineffable emotional complexity, slowing down time as the camera gently drifts by Alexander standing motionless among black trees on a snow-covered ground, or elsewhere submitting us to the rhythmic trickling of water as it leaks through a ceiling and pools on the floor. As if filtered through the prism of one man’s existential trepidation, Tarkovsky casts a delicate ethereality across the earthy textures of his mise-en-scène, capturing actors and props in precisely arranged shots that might collapse with the slightest atmospheric shift.

Especially when prophetic visions begin to intrude on Alexander’s consciousness and reveal an impending apocalypse, Tarkovsky lulls us into a soothing despair in a desolately ruined courtyard, tilting the camera downwards to close-ups of the debris below. Wet newspapers caught in a dirty stream, a single wooden chair remarkably still standing, and a glassy reflection of the ruined city above illustrate the remnants of some pending disaster, while Tarkovsky’s camera floats overhead. The black-and-white grading of this shot is devastatingly bleak, emphasising the ash fluttering through the air while light disappears entirely into the burnt interior of a wrecked car, foreshadowing a progressive colour desaturation of the entire film from the moment Alexander’s eerie dreams manifest in his reality, and war is officially announced.

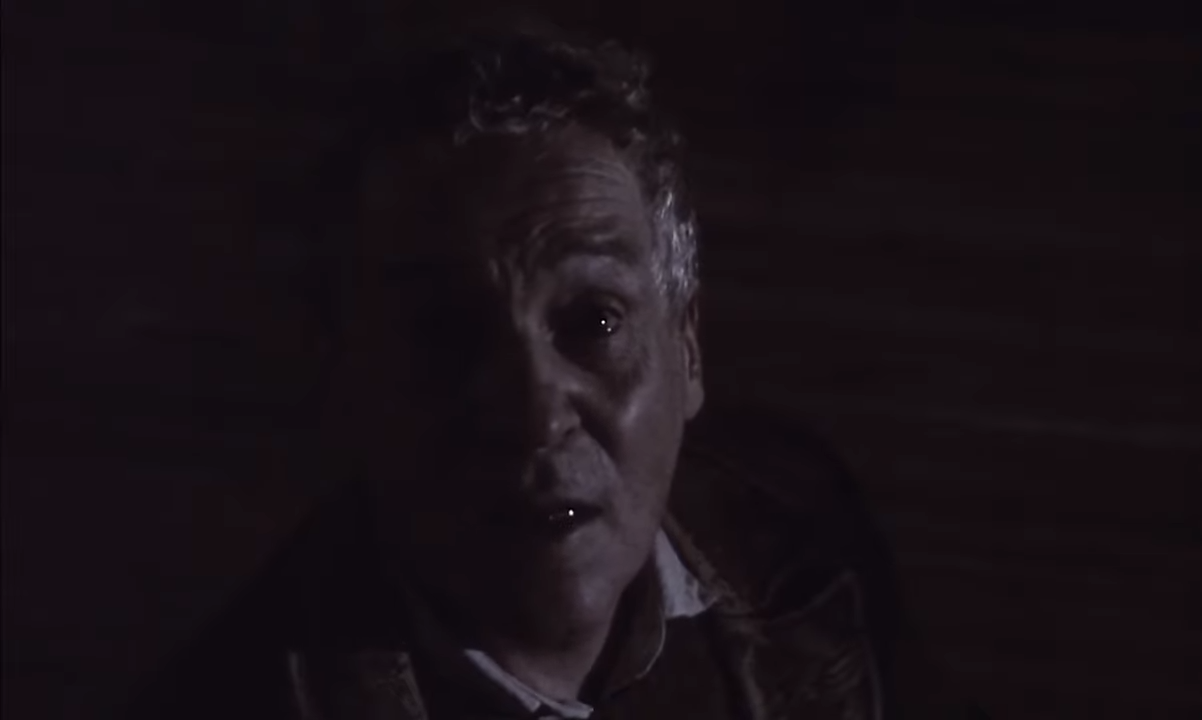

The news immediately dampens the spirits of Alexander’s party, settling ominously over a composition of eerie disconnection, with each guest facing their body outwards from a round table while their gazes are fixed on the flashing television light in the background. Their reactions are diverse – after Alexander’s wife Adelaide is sedated from her hysterical outburst, he quietly disappears upstairs and begins muttering the Our Father in anxious desperation. Josephson has never given a greater performance than he does here, his breath shaking and eyes wide with tears as he collapses to his knees, frantically trying to strike a deal with the God he has not prayed to for a long time.

“I will give Thee all I have. I’ll give up my family, whom I love. I’ll destroy my home, and give up Little Man. I’ll be mute, and never speak another word to anyone. I will relinquish everything that binds me to life, if only Thou dost restore everything as it was before… as it was this morning and yesterday. Just let me be rid of this deadly sickening, animal fear! Yes, everything!”

Very slowly, Tarkovsky pushes us forward into a close-up of Alexander’s fearful face as he misses the contradiction of his intended sacrifice. If the world is to end the way he expects, then all that he is offering now will be destroyed regardless, thus rendering the propitiation useless. Still, in the madness of his terror, this goes entirely ignored. The Sacrifice does not impose judgements of whether Alexander may be a madman, a coward, or an altruist, leaving just enough in the subtext for us to find our own connection to him, though one thing is made undeniably clear – his habitual self-reliance has been rendered totally inept in the face of such immense existential dread. How can we blame him for resorting to such extreme, unfamiliar methods?

Alexander’s newfound faith is driven by fear, not love, and as a result his devotion is totally fragile. He is willing to hang all his material possessions on the tiny chance that God will bring salvation, while hedging his bets that other pagan forms of spirituality might do the same. Having learned from Otto that his housemaid Maria is a witch who can help him save the world, he approaches her with an open mind, ready to perform whatever ritual she asks.

Hunched in shame, he tells her another parable mirroring that of the devoted monk which opened the film, though this time it is a personal confession of the time he accidentally ruined his mother’s beautiful garden, despite his good intentions. Grace has been escaping him his entire life, he believes, and to recapture it now would earn his redemption. Soothing his anxiety, Maria wraps him up in a coital embrace, floating and rotating weightlessly above the bed. Jet planes continue to fly overhead, yet through this surreal, ritualistic imagery The Sacrifice offers a tranquil hope for deliverance.

In the film’s broader symbolic reflection between paganism and Christianity though, there is also a mirroring between the act of life-giving creation that Alexander performs with the witch, and the act of blazing destruction he dedicates to God in the film’s grand climax. Not content that his bizarre sexual encounter was enough to save the world, he follows through on his initial promise, stacking wooden furniture inside his house before setting it alight. Outside, Tarkovsky commences one of the single most impressive shots of his career – a six-minute take sitting several metres high off the ground, watching this giant wooden structure burn to its charred bones.

How ironic that one of the great cinematic set pieces of the 1980s emerged not from any Hollywood blockbuster, but from a Soviet director whose artistic inclinations are almost diametrically opposed to his American contemporaries. That Tarkovsky’s initial effort to coordinate this breathtaking sequence was ruined by a camera malfunction makes the feat all the more admirable, as the entire house had to be rebuilt in two weeks for the second take that eventually made the final cut. His dedication to harsh, elemental visuals pays off enormously too in the fire’s contrast against the cold island landscape around it, reflecting its dazzling orange light in the surfaces of stagnant puddles, and restoring colour to the heavily desaturated film. Beneath the enormous plumes of smoke and flames billowing into the air, Alexander is but a tiny, shrunken figure running madly about in a black kimono, trying to escape the reach of his family and the paramedics who have seemingly turned up out of nowhere.

Beyond the spectacle, it is also astounding how much character detail Tarkovsky instils in this shot. Given the sudden arrival of these ambulances, one must wonder whether Alexander’s birthday party was really a final farewell before committing him to a mental institution, which then leads us to question how much of what we have witnessed have been the delusions of an unwell man. Alternatively, this could also be evidence of a world that cannot understand his true spiritual enlightenment.

For those who take Alexander’s offering to be totally futile, Tarkovsky’s final scene keeps The Sacrifice from becoming a totally pessimistic tale. He employs his biblical metaphors with care, drawing multiple connections to the fall of man and Abraham’s sacrifice of his son Isaac, but the only true miracle among them arrives with Little Man’s first words as he lays beneath the withered tree from the film’s opening.

“In the beginning was the Word. Why is that, Papa?”

Quoted from the Gospel of John, Little Man appears to carry on a faith that is scarce to be found elsewhere on this island, and which was tainted in Alexander’s pure self-interest. The parallels to a virtually identical miracle at the end of The Seventh Seal indicates yet another tie to Bergman too, though where the previously mute servant girl there greets Death with Christ’s words “It is finished,” Tarkovsky’s selected bible passage implies a spiritual hope. Therein lies the greatest philosophical division between the two auteurs. Alexander’s sacrifice may or may not have averted the end of the world, but as Little Man dutifully waters his father’s tree, we can at least be assured that Alexander’s demonstration has planted the seeds of faith for future generations.

The Sacrifice is not currently streaming in Australia, but can purchased on DVD and Blu-ray here.

Pingback: The 100 Best Male Performances of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Shot Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Cinematographers of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Directors of All Time – Scene by Green