David Fincher | 1hr 58min

Michael Fassbender’s dead-eyed assassin goes by no name other than that which is presented in the title of The Killer. He serves no god or country, and refuses to take sides in his clients’ affairs, instead dedicating his entire mind and body to the task at hand with extraordinary patience. “Forbid empathy. Empathy is weakness. Weakness is vulnerability,” his inner voice repeats, like a mantra of short, staccato instructions inducing a state of complete detachment. “Anticipate, don’t improvise. Trust no one. This is what it takes to succeed.”

Why then does The Killer see him tread the fine line between success and failure so frequently? It is a trend that begins to unravel right from the opening scene when, after spending days staking out a Parisian hotel room from an abandoned apartment across the street, he misses his target and hits an innocent woman instead.

The error is as shocking to us as it is the Killer himself. He is a man who has refined his craft through self-control and routine, keeping his inner voice from wandering by listening to The Smiths, and tracking his heart rate through a smartwatch. He may believe himself to be immune to human error, and yet it is exactly this which rears its head all throughout The Killer. Much like Michael Corleone claiming in The Godfather that his work is not personal but just business, there is a tension between this hitman’s voiceover and his actions. After all, as much as he would like to believe otherwise, the quest for vengeance that he sets out on shortly after this deadly slip-up is driven by nothing but his own furious desire for justice.

With such a vast emotional distance established between audience and character in The Killer, it is no wonder why David Fincher was drawn to its methodically structured screenplay. Murderous psychopaths have long been at the centre of his meticulous narratives ever since Seven, and even when his focus has drifted to less lethal subject matter in films like The Social Network, there still resides a vague hollowness in his characters. Still, The Killer delivers an icy interrogation of this mindset so distinct from any of those previous films that it is surprising Fincher hasn’t explored the psychological territory of a professional assassin sooner. Jean-Pierre Melville’s neo-noir crime films have long been an influence on Fincher’s work, and so it was only a matter of time before he remodelled the rogue hitman story of Le Samouraï into his own painstaking character study of cold-blooded perfectionism and stifled vulnerability.

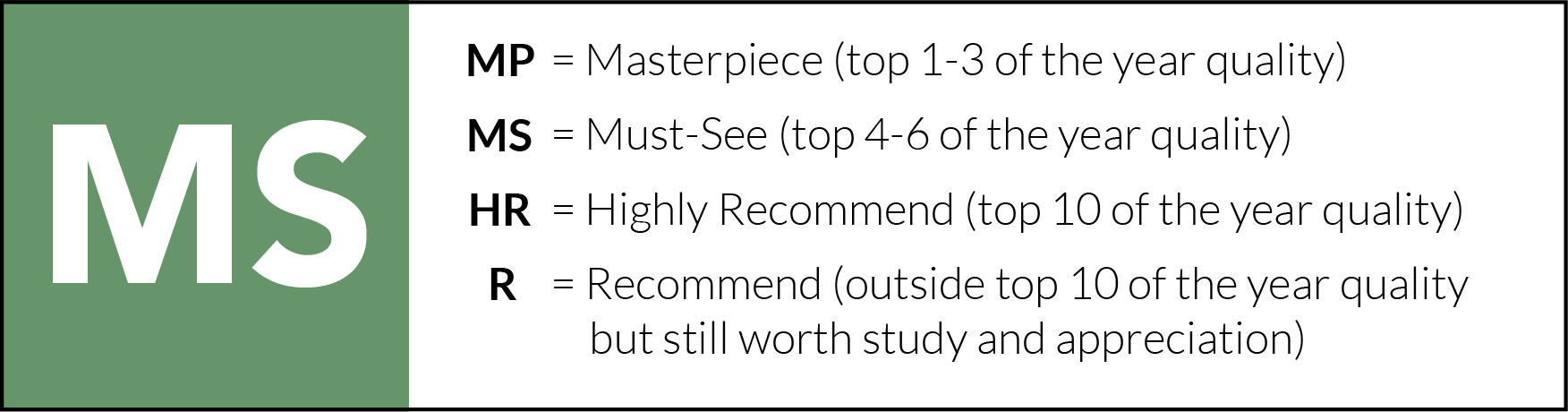

Like Melville, Fincher is also a dedicated technician of film lighting and colour, though much preferring his desaturated golden palettes and pronounced shadows over the French auteur’s cool blue washes. The Killer is formally divided into six chapters, each set to a different city made visually distinct by their architecture and weather, and yet it is that consistency in Fincher’s gloomy, yellow aesthetic which formally unites these locations within a treacherous underworld. Whether he is stalking a taxi driver along the tropical coasts of the Dominican Republic or a fellow assassin through the snow-blanketed streets of Chicago, the Killer’s silent operations are shrouded in shadow.

It is the highly controlled soundstages where Fincher is at his strongest though. The sources of his ambient lighting setups are frequently part of the scenery, with reading lamps, fluorescent battens, portable floodlights, and other fixtures decorating everything from high-end restaurants to bare apartments. It is thanks to these visible light sources that Fincher holds such a command over his darkness as well, letting us lean forward to pick out the incredible detail of his compositions without letting it entirely disappear.

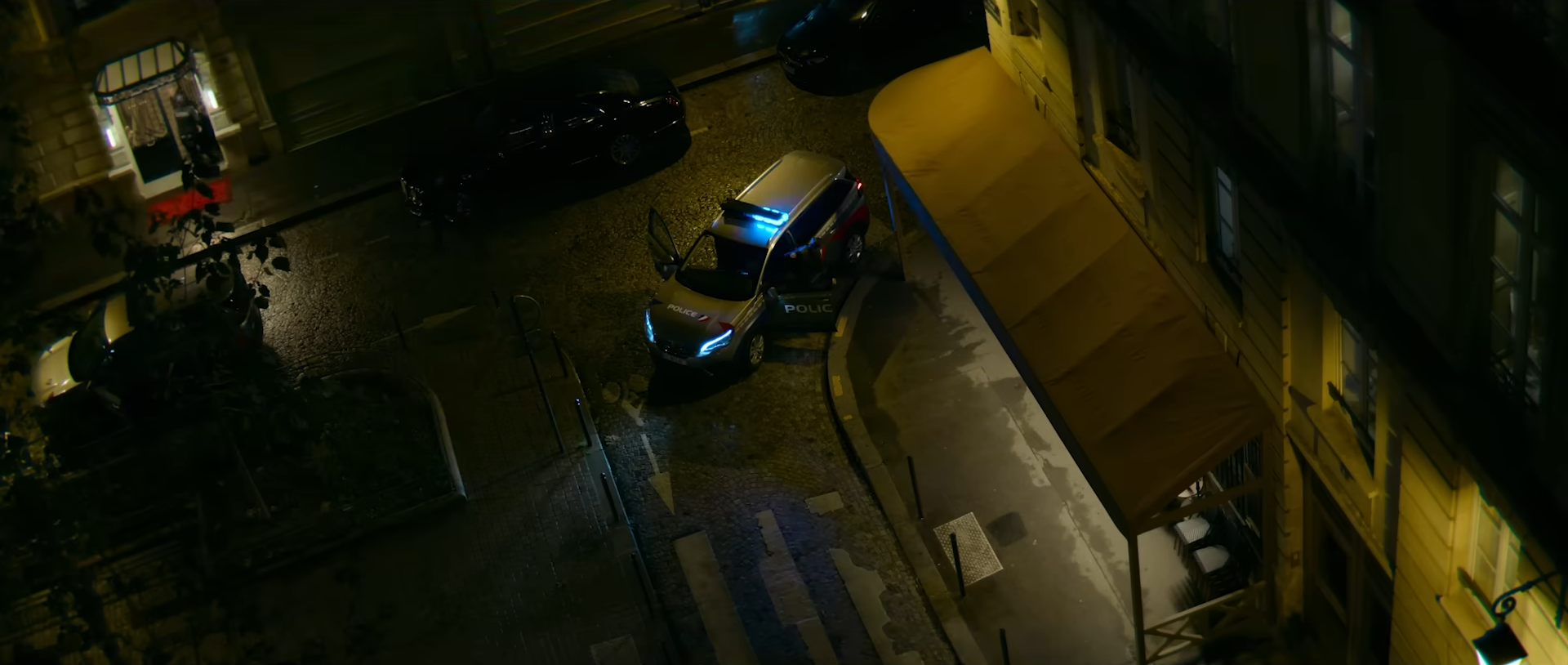

It is a level of aesthetic precision that is not unusual for Fincher, but which here makes for a perfect formal match to the Killer’s slick, patient procedures, fastidiously traced through long stretches of purely visual storytelling accompanied only by that taciturn voiceover. “If you are unable to endure boredom, this work is not for you,” he informs us, and indeed the large majority of his work does not simply involve killing, but rather travelling, tailing, infiltrating, and waiting around to spring into action. Though he claims to have no affiliations, it is in these mundane moments that his idiosyncratic habits come to light – taking the bread off his breakfast muffins, for instance, or his routine stretching.

After years of working in franchises and briefly taking a hiatus from acting altogether, Fassbender’s return to auteur collaborations is very welcome here, applying an intensive focus to every action and thereby compelling us to do the same in our observations. Conversely though, the flashes of anger and panic that cross his impassive face whenever he is faced with unexpected diversions also develop a growing sense of unease, building to a violent climax when he is ambushed by a brutish hitman with multiple advantages over him.

Fassbender’s unblinking Killer may have a quick mind and agile body on his side, but he is not a machine, flawlessly executing plans with pinpoint accuracy. He is prone to errors, riddled with weaknesses, and perhaps even capable of the empathy he so frequently derides. Whether or not he can accept this, he cannot simply will his imagined supremacy into existence by repeating the same empty affirmations. This wannabe psychopath does not belong among the few who are truly void of emotion, but among the many who willingly fall victim to it, vulnerable to an innate humanity that limits perfectionism, yet equally expands our self-understanding.

The Killer is currently streaming on Netflix.

Pingback: 2024 Oscar Predictions and Snubs – Scene by Green

Pingback: The Best Films of 2023 – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Male Actors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: 2023 in Cinema – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 10 Best Film Editors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 25 Best Directors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green