Martin Scorsese | 3hr 26min

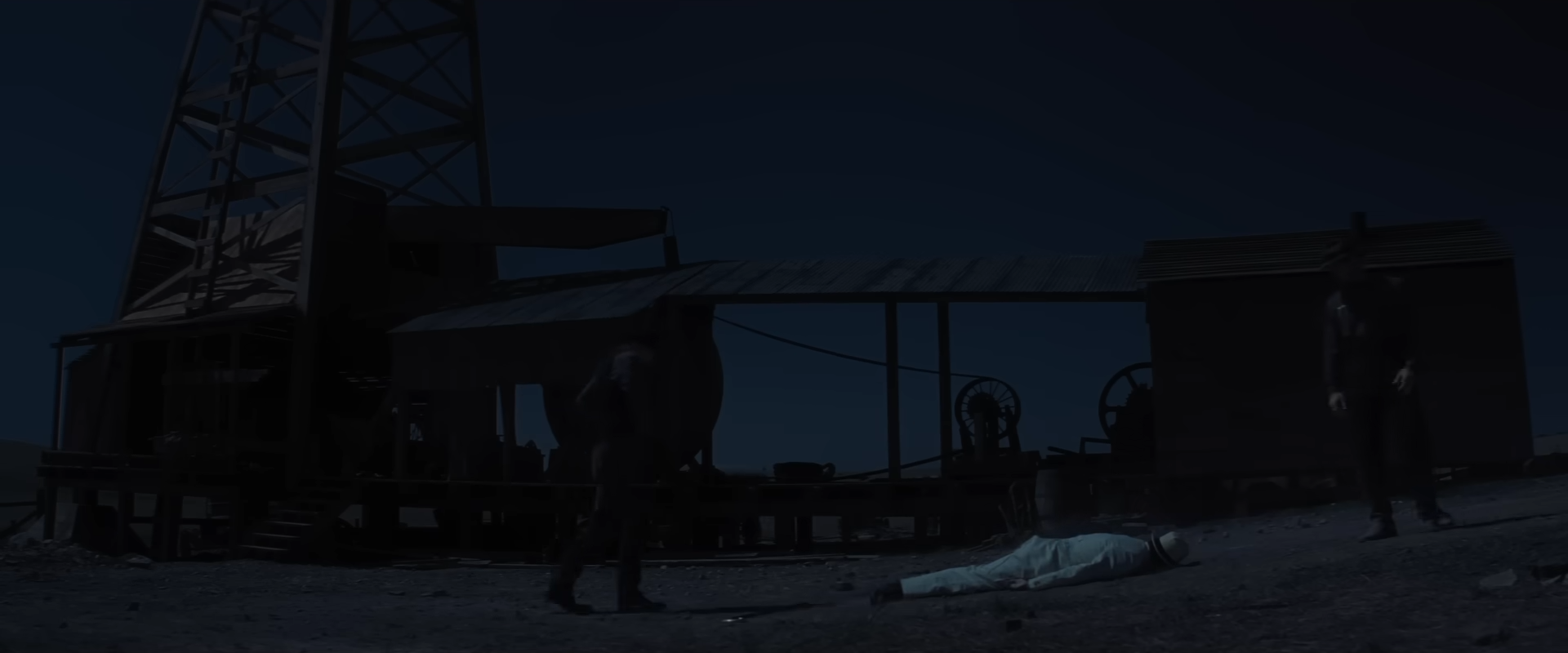

The Osage Nation had already suffered one great upheaval in the 19th century when the United States government forced them to relocate from Kansas to Oklahoma, cutting them off from their historical and cultural roots. Given the discovery of abundant oil in their new territory almost immediately after the funerial burial of a ceremonial pipe though, it appears as if the spiritual forces of nature have come to deliver them from their tribulations, sending manna from heaven that guarantees them a prosperous future. From their great loss springs new life, but while “the chosen people of chance” dance in slow-motion beneath the gushing well of newfound riches, the colonial powers that be are not so ready to let this opportunity slip through their fingers.

Just as Martin Scorsese seems to have had his final say on the gangster genre with The Irishman, a new spate of violent assassinations and underground conspiracies emerge in 1920s Oklahoma, though the victims in Killers of the Flower Moon are not rival mobs or compromised associates. The primary orchestrator of this plot is William King Hale, a wealthy rancher who purports to be a good friend to the Osage people, speaks their language, and even offers a reward to whomever comes forward with information regarding their senseless murders. He has the untouchable evil of Noah Cross from Chinatown, and yet Robert de Niro applies a genteel Southern charm to this chilling façade of warmth, consequently giving his best performance in almost thirty years.

From the perspective of the FBI agents coming to investigate these murders, this narrative could have very easily been a murder mystery, and indeed the early drafts of Scorsese and Eric Roth’s script were close to following this route. As it is, Killers of the Flower Moon does not play this game for very long, explicitly revealing which men have been killing the Osage people, and under whose orders.

At the centre of Hale’s plot as well is a cross-cultural marriage intended to grant him a large portion of the local wealth, and his nephew Ernest Burkhart is perfectly positioned in this matter. There is no doubt his budding romance with Osage woman Mollie Kyle is at least partly genuine, but there are few characters here as stupidly craven and weak-willed as him. He is a pawn in his uncle’s long game, blowing up his neighbour’s home and poisoning Mollie through her insulin shots, and yet somehow still finding the audacity to feel guilt over his despicable actions as he obediently carries them out.

This is the first time since This Boy’s Life in 1993 that Leonardo DiCaprio has starred opposite de Niro, and though there is a palpable screen chemistry between the two defining actors of their generations, Lily Gladstone stands toe-to-toe with them as the unfalteringly resilient Mollie. Having made a small name for herself in Kelly Reichardt’s indie dramas over the past few years, she now brings her softly spoken yet self-assured presence to a larger canvas, letting those moments where grief and fury break through her usually composed demeanour land with absolute devastation. Even as she pursues justice for her people, there is little that can sway her from her husband’s side, convincing herself that he may be the only innocent white American in the entire county. After all, how could anyone keep such a dangerous lie from their own family for so many years?

Just as the enormous running time of The Irishman sinks in the sad weight of a former hitman’s hollow life, the fact that the crimes depicted in Killers of the Flower Moon continued for so long without any legal ramifications is made all the more despairing by its sprawling scope. With a pace that thoroughly teases out each side character and subplot, Scorsese fully realises the enormous depth of this divided community, and further brings its setting to life through his authentic production design and sweeping camerawork.

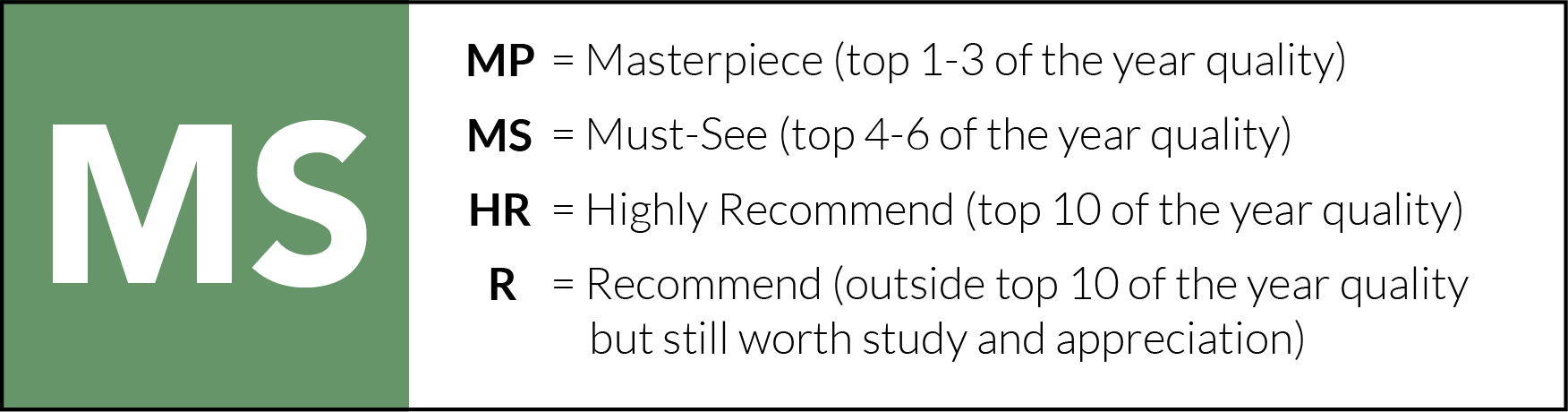

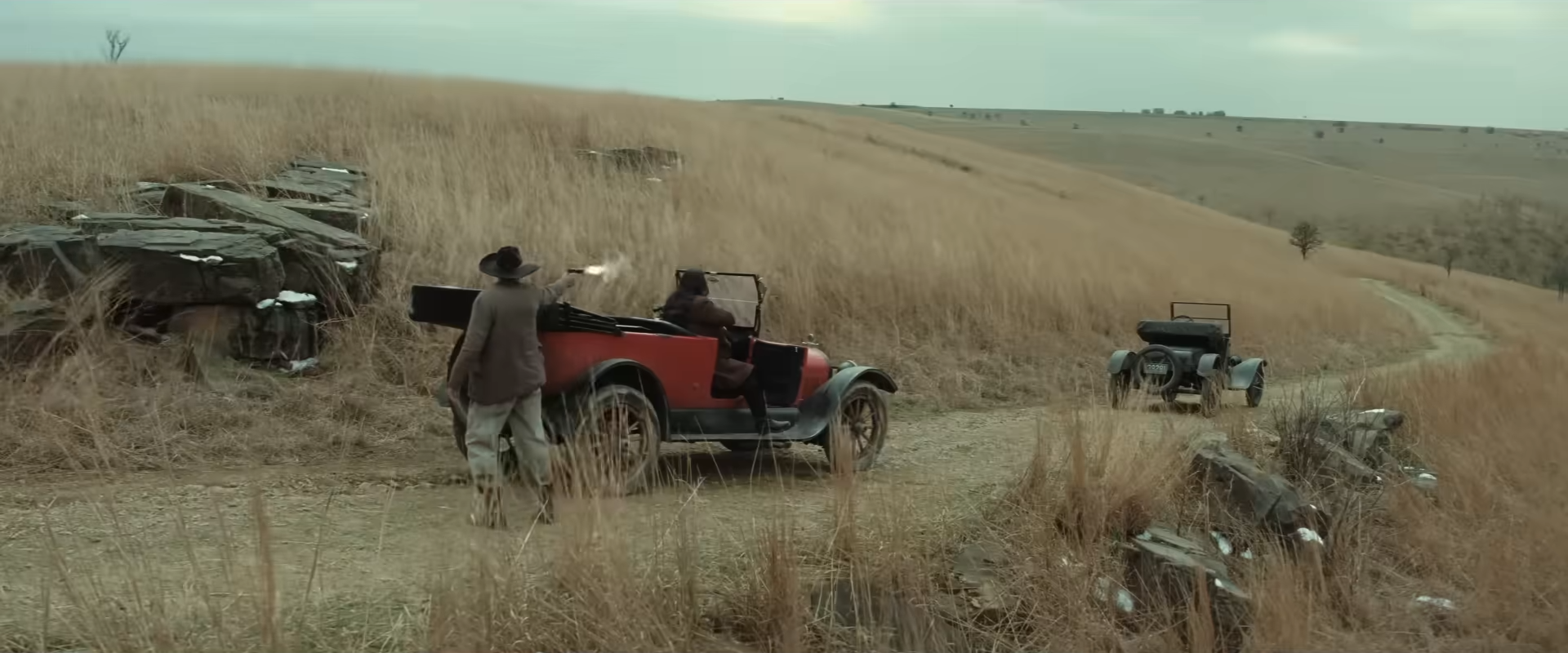

There is a touch of Sergio Leone in these dynamic long shots, craning up above train stations, rural settlements, and oil fields to reveal the marks of white colonisers seeking to capitalise on the Osage people’s wealth, but Scorsese does not relinquish his own visual style so easily either. In one long take, he tracks his camera through a busy house hosting a party of Native Americans, and later when a ranch burns to the ground he envelops us in Ernest’s guilt-ridden fever dream, distorting silhouettes of men trying to fight the fire through its ethereal, orange haze. Hale and his men have unleashed hell on Earth, and there is little salvation to be found in this biblical blaze, embodying a fast-spreading, bitter derangement that sees a self-loathing Ernest drop a small dose of Mollie’s poison into his own whiskey. Conversely, Scorsese also draws on the animalistic iconography of Native American spiritualism, twice over haunting those targeted by Hale’s men with owls – an omen of death in many tribes.

In moments like these, Killers of the Flower Moon shifts away from the impression of factualism and reveals the inherent subjectivity that comes with dramatising history. Composer Robbie Robertson’s fusion of bluesy guitar riffs, humming vocals, and traditional pipes accentuates this point in its anachronistic delirium, and sadly marks his final film score before his passing earlier this year. Its formal consistency is unfortunately not a feature shared by the silent newsreel interludes that almost completely drop off after the first half hour, or the fourth-wall shattering epilogue that lacks any kind of setup. In moments like these, Scorsese’s film reveals itself to be a slightly more uneven work than The Irishman, angling at some critical point about reconstructing the past through storytelling, but never quite unifying it with the broader narrative.

As far as historical epics go though, Killers of the Flower Moon does not waste its length, and Scorsese’s reflections on the racial tensions of 1920s Oklahoma are never oversimplified. White man’s fetishisation of Indigenous people’s ethnic purity and skin colour is often written into the subtext of their creepy exchanges, and the Native American symbol of abundance represented in the titular ‘Flower Moon’ is effectively tarnished by the timing of Hale’s genocide.

This is a two-faced villainy bred not from ignorance, but from an intimate knowledge of one’s economic rivals, and the capitalistic belief that only the ruthless deserve to prosper. Not even family ties will stand in the way of Hale’s accumulating wealth, and the justice eventually delivered by America’s legal system is only a half-hearted indictment of the perpetrators accountable when their web of lies begins to unravel. For once, the existential despair that Scorsese leaves us with does not hang solely on his criminal characters and their catastrophic life choices. In the end, Killers of the Flower Moon is just as much a wistful lament for the exploitation of America’s Indigenous people, and the trust many of them placed in allies with warm smiles and greedy hearts.

Killers of the Flower Moon is currently playing in theatres, and will soon be streaming on Apple TV Plus.

Pingback: 2024 Oscar Predictions and Snubs – Scene by Green

Pingback: The Best Films of 2023 – Scene by Green

Pingback: 2023 in Cinema – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 25 Best Male Actors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 10 Best Film Editors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 25 Best Directors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green