Sidney Lumet | 2hr 4min

Over the course of a few hours on one hot summer day, crowds congregate around the First Brooklyn Savings Bank in New York City, with journalists and television crews eventually joining the mix. Inside, a failed heist has turned into a police stand-off, with the two robbers taking the entire building hostage, and incidentally providing a bit of light entertainment for the masses. A pizza delivery guy milks his time in the spotlight when he brings lunch around, and the head teller excitedly flirts with the cameras while being used as a human shield, momentarily putting aside the present danger to feed her ego.

It appears for a time that Sonny, the brains behind the operation, doesn’t mind the attention either. Despite being out of his depth in this robbery gone wrong, he quickly learns that many viewers see him as a hero of the common man, railing against the police and throwing cash out to feverish onlookers. A small riot starts as they burst through the barricades, undermining the police’s attempts to control the situation, and yet media sensationalism is an unwieldy beast. When a more complicated portrait of Sonny begins to emerge, revealing a man desperately seeking money for his transgender wife’s gender affirming surgery, audiences aren’t quite sure how to reconcile that with their preconceived notions. The breaking news story soon becomes solely about his queerness, and the praises once thrown his way become nasty jabs. There is no regard here for the figure at the centre of it all, rich with flaws and personal struggles. Looking in from the outside, he is just the latest television character to capture the fleeting interest of the public.

This is not the perspective Sidney Lumet decides to take in Dog Day Afternoon though. The real events upon which the film is based are readily available in historical records, while this fictional interpretation lends a greater sensitivity to those trapped inside the bank. The false confidence that Sonny and his friend Sal initially project dissipates almost instantly when the third part of their trio, Stevie, nervously backs out and leaves them stranded. They have clearly never done anything like this before, caving a little too easily to the demands of their hostages and even developing somewhat friendly relationships with them. These are not the heroes nor sick-minded villains that the media would like to believe – merely short-sighted victims of their own poor decisions.

The uneasy nuances of these characters offer a wealth of rich material for both Al Pacino and John Cazale to deliver two standout performances as well. In Cazale’s case, Dog Day Afternoon would be the second-last film of his short career before passing away in 1977, though he makes every minute of his screentime count as the nervous, simple-minded Sal. He partly serves as comic relief from time to time, telling Sonny that the country he would want to escape to most of all is Wyoming. Most of all though, we feel pity towards this man who takes offence at being mislabelled a homosexual, and who we come to realise is too easily exploited by both the police and his own friend.

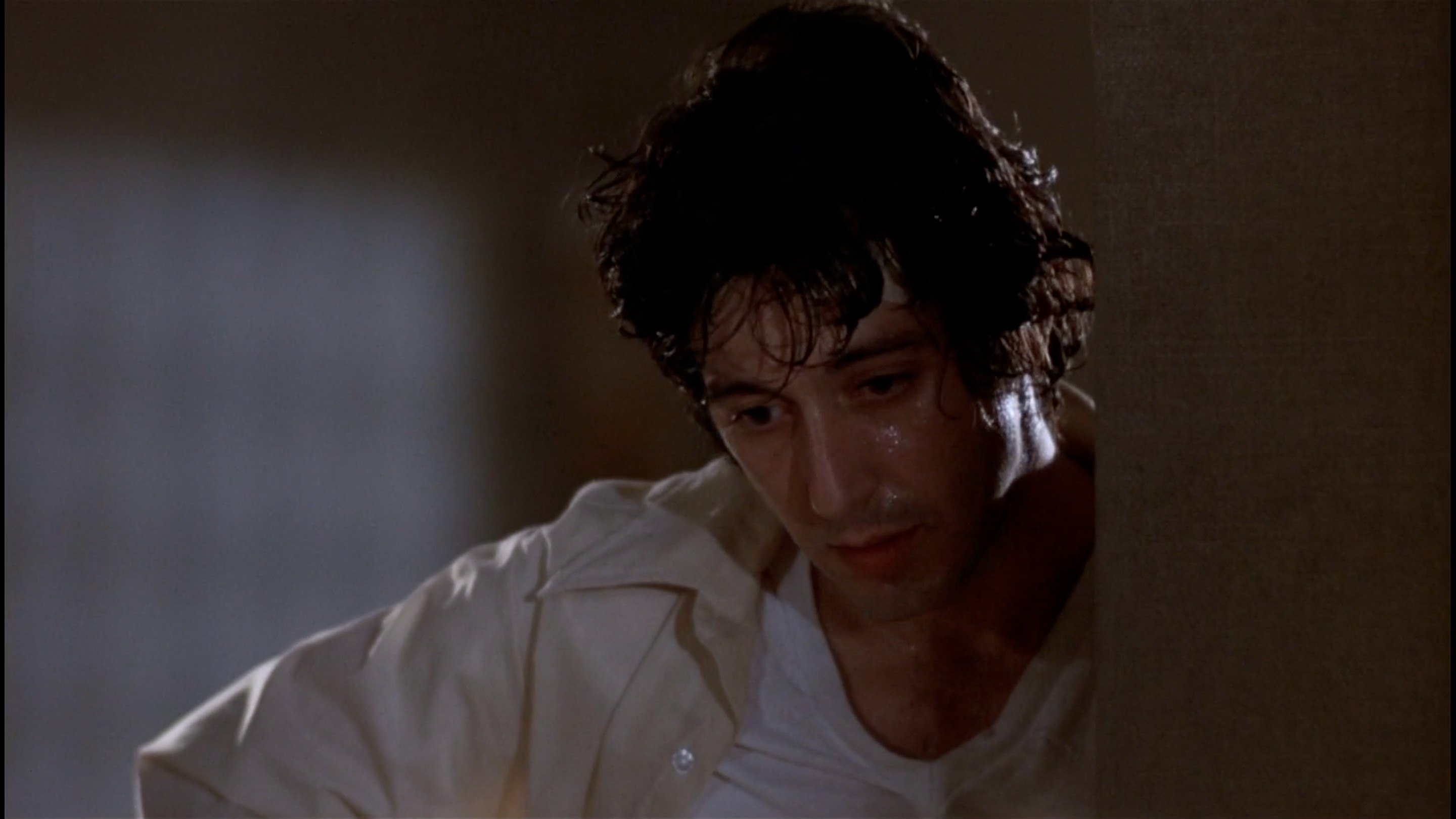

The true tour-de-force of acting in Dog Day Afternoon comes from Pacino though, who in 1975 was coming off a hot run of the first two Godfather films and Serpico. His portrayal of Sonny treads a fine balance between the deep, internalised performances of his early career and the loud personas he would play further down the line, generating an instability that cuts through layers of insecurity and anger. His incendiary evocation of the Attica Prison riot which saw police carelessly mow down hostages and inmates alike becomes a powerful catch cry as he furiously paces outside the bank, inciting a righteous anger in the anti-authoritarian crowds.

Still, the longer we sit with him inside, the more we understand the sensitivity of those wounds being picked at by the mass media. His trans wife Leon has been hospitalised for attempted suicide and now, despite Sonny’s good intentions, wants nothing to do with these criminal plans, while his estranged cis wife Angie laments his stubbornness and abandonment of their family. Even his mother is brought in to help the situation, though she is insistently blind to his culpability, blaming everyone in his life but him for his own mistakes. Sonny may be reckless, but he does not lack self-awareness, as Pacino’s face slowly breaks down with guilt, self-loathing, and a tragically weakened resolve over the course of the film.

On top of all that, Lumet never quite lets us forget the physical factors of the environment that Sonny must contend with, observing the sweat form on his face from both the humid summer heat and the sheer stress of the stand-off. Though Lumet is picking up a few techniques from Hitchcock with the long camera takes and tight, suspenseful editing, he is largely committed to the authenticity of the piece. By and large, Dog Day Afternoon does not draw the same breathtaking beauty out of its New York location shooting as we see in The French Connection or Taxi Driver, and yet there is still a cumulative effect in the grounded urgency of its gritty aesthetic and pacing, pulling a highly-strung Pacino into an uncontrollable whirlpool of rapidly escalating stakes.

Paramount to Lumet’s realism is the pained sympathy he has for these complicated characters, both naively believe that some happy ending is still possible at the end of it all. When the two men finally secure a deal that will let them fly out of the country, one of their hostages takes the time to comfort a nervous Sal who reveals he has not been on a plane before. It is a small twinge of unexpected kindness in an otherwise tense sequence, enveloped by Lumet’s cutting between Pacino’s anxious face and the suspicious police activity unfolding around him.

Dog Day Afternoon’s denouement unfolds rapidly from there – a fatal shot to Sal’s head ends his life before he even knows what’s going on, while Sonny is arrested at gunpoint. The shame we have seen him bear throughout the film is nothing next to the guilty anguish on his face as he watches Sal’s body taken away, recognising the role he played in the death of his far more innocent friend. Within this great tragedy though, Sonny’s delicate story of queer love and financial desperation was never going to survive the noise of sensationalist journalism. All that is left is a cheapened legacy embedded in New York’s quirky local history, destined to be recalled by strangers as that bizarre, failed bank heist they spent one hot, summer afternoon following on television.

Dog Day Afternoon is currently streaming on Binge, and is available to rent or buy on Apple TV, YouTube, or Amazon Video.

Pingback: The 100 Best Male Performances of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Male Actors of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Film Editors of All Time – Scene by Green