Pablo Larraín | 1hr 50min

The grotesque metaphor that El Conde poses is simple enough in its Gothic iconography, comparing Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet’s legacy to that of a vampire parasitically living off society’s most vulnerable. The social context surrounding Pablo Larraín’s satirical target certainly hits closer to home for the director than the other cultural figures he previously examined in Jackie and Spencer, and yet there is a universality to this historical revisionism which sees Pinochet take his oppressive totalitarianism to the world stage.

Horrified by the subversive violence he witnessed in his youth fighting against the French Revolution, this fictional version of the famous tyrant subsequently spent centuries combatting further uprisings across the world, before beginning his despotic reign in late twentieth century Chile. Larraín’s sardonic depiction of Pinochet is not so much a faithful rendering of the former president as he is an outlandish icon of dictatorship, feverishly feeding on citizens of the working class who won’t be missed, while his disloyal inner circle desperately hope that their close acquaintance might grant them their most selfish desires.

After many years of estrangement, the five Pinochet children who have denounced their father’s evils arrive at his hidden estate in the Andes to claim their inheritance, hypocritically disregarding how the fortune was unethically amassed. The nun who has come to exorcise the devil from his body also falls hard for his seductive promises of power, inspiring jealousy in his wife Lucía who wants nothing more than to be bitten and become similarly immortal. As for the retired dictator himself, there is very little tethering him to his miserable half-life, leaving him to consequently give up drinking blood and let himself die. If only it were that simple – the curse of vampirism has doomed an aged Pinochet to eternal banality, never quite regaining the vitality of his youthful rule, and equally never finding the cold release of death.

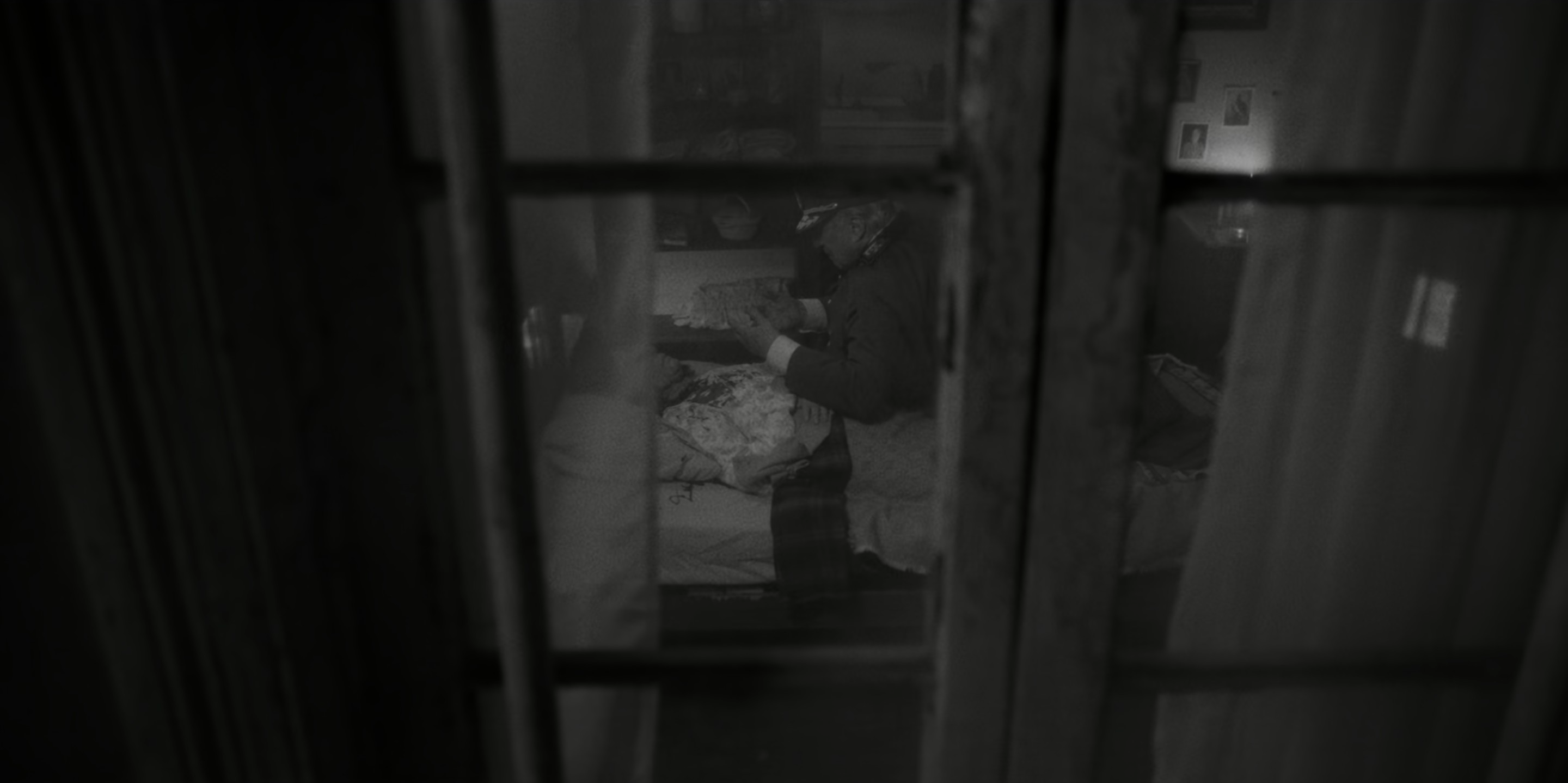

Right from the opening credits, Larraín’s bright pink font sardonically nods at the campness underlying the darkness of Pinochet’s decrepit existence, though between here and the final scene he does not waver from his bold, monochrome aesthetic. The harsh silhouettes cut out from Pinochet’s caped figure as he stands alone in Gothic interiors bear striking resemblance to the Iranian vampire film A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, but the severe landscapes of foggy coastlines and mountains call back even more distinctly to Ingmar Bergman’s early work in The Seventh Seal. With Pinochet standing in for the physical manifestation of Death, Chile’s cities and countryside are similarly haunted by unholy abominations and mysterious deaths, revealing a rot that has infected the soul of humanity – not explicitly the result of an absent God, but rather the lingering trauma of modern fascism.

As Larraín would have it, God in fact plays a very active role in this dark fairy tale, distorted through the corrupt vessel of the Roman Catholic Church. Sister Carmen emerges like a spectre from a choir of white-clad nuns in a vast, stony cathedral, prophesied to “destroy dreams and bring misery” with her “white, innocent flesh.” Disguised as an accountant, she enters Pinochet’s estate and immediately charms the vampire with her fluent French, before sitting down with each family member and conducting a thorough audit of his extraordinary wealth. Larraín lands us right in the middle of these interrogations too, intimately centre framing both Carmen and the subjects of her probing as they spill secrets of Pinochet’s criminal exploits, figuratively embodied in parallel scenes of his vicious, bloody hunt.

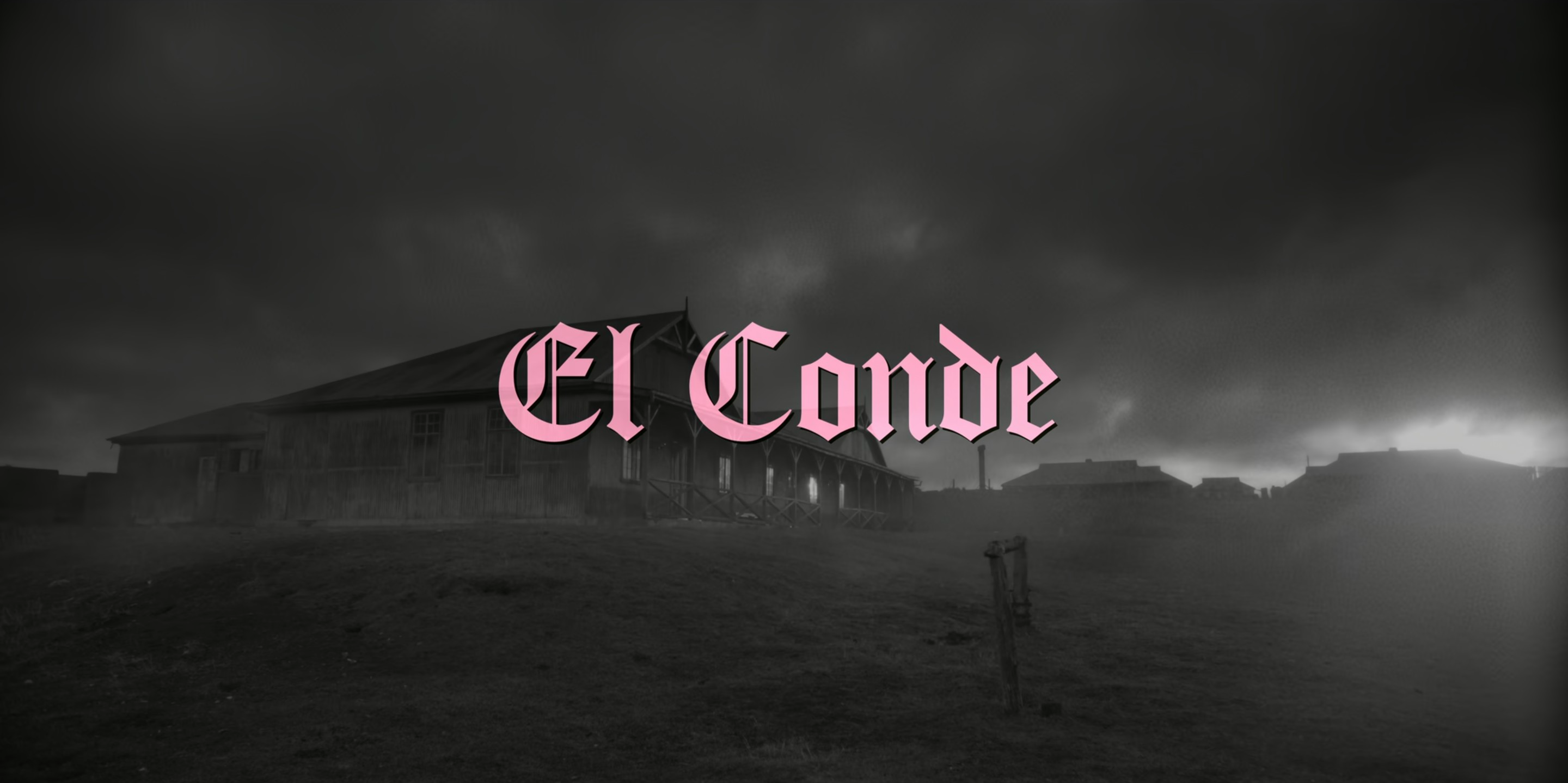

The intercutting here is harsh in its visual juxtaposition, associating tales of Pinochet’s unrestrained political power with images of him ravenously licking the blood of an elderly woman off his fingers, and disembowelling a labourer working a late-night shift. His legacy has not been officially memorialised through busts in Chile’s presidential palace, leaving him to pathetically fill his own empty spot among its sculpted leaders, and yet it continues to creep into the homes and workplaces of ordinary citizens who still feel its insidious reverberations.

If there was any hope of good triumphing over evil in El Conde, then it lies in Carmen and her holy quest to rid the world of Pinochet once and for all. As she grows closer to her target though, another political allegory begins to emerge, chillingly illustrating a conspiratorial alliance of the church and state. As she takes to the overcast skies and learns to fly for the first time after being turned, Larraín delivers what may be the singularly most beautiful scene of the film, floating his camera along as she awkwardly tumbles and falls over Pinochet’s farm like Jesicca Chastain in The Tree of Life. Just as her clumsy flailing strikes a very different image to his smooth gliding over cities and islands, her billowing white robe also contrasts boldly against his black cape stretched out behind him, framing them as two halves of a single power – light and dark, youth and old age, church and state.

Unfortunately for Carmen though, this romance will only survive for as long as it serves her new master. Pinochet’s gruesomely comical obsession with Marie Antoinette serves up the perfect inspiration for his muse’s latest look, ironically imposing on her an oppressive control that bears significant resemblance to the French Queen’s deprived agency in her own lifetime. The arrival of a new power on the estate also brings a sharp end to her story beneath the blade of a guillotine, finally revealing the identity of our mysterious narrator whose clipped British accent and English speech has curiously mismatched the rest of the cast’s Spanish and French.

Larraín’s hilariously flamboyant twist will not be spoiled here, but the global cabal of blood-sucking vampires it paints out with dark humour can at least be mentioned without ruining any major surprises, expanding the scope of El Conde’s satirical revisionism. While the descendants of fascism are quietly profiting off its hoarded plunder and its self-interested lovers are realising they are only safe for as long as they remain useful, the only other figure that can truly understand a tyrant like Pinochet is a fellow tyrant. “This is what the count achieved,” our notorious narrator acutely observes. “Beyond the killing, his life’s work was to turn us into heroes of greed.”

These immortal manifestations of authoritarianism have spent their entire lives putting revolutionaries across the world in their place – not always succeeding, but never dying out either. History traps us in a cycle of never learning from our own mistakes, and so while the man known as Augusto Pinochet may have withered away, Larraín pessimistically hints at a younger form of totalitarianism restoring its historical ideals. El Conde’s formal switch from black-and-white to colour in the final scene may offer its Gothic aesthetic a similar rejuvenation, though the dark, angry hearts of these human parasites continue to beat in the chests of future generations, waiting for the day humanity grows complacent enough to let a new Pinochet kill and pillage their way to unlimited power.

El Conde is currently streaming on Netflix.

Pingback: 2024 Oscar Predictions and Snubs – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 25 Best Directors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green