Max Ophüls | 1hr 56min

It is tempting to glamourise the life of Lola Montès, the famed dancer and courtesan who ventured across multiple continents and conducted affairs with some of 19th century Europe’s most famous men. After all, there are few women who can honestly say that their paths have intersected with so many key historical events, and even fewer who have used each as a platform to propel themselves higher up a cultural hierarchy that once towered above them.

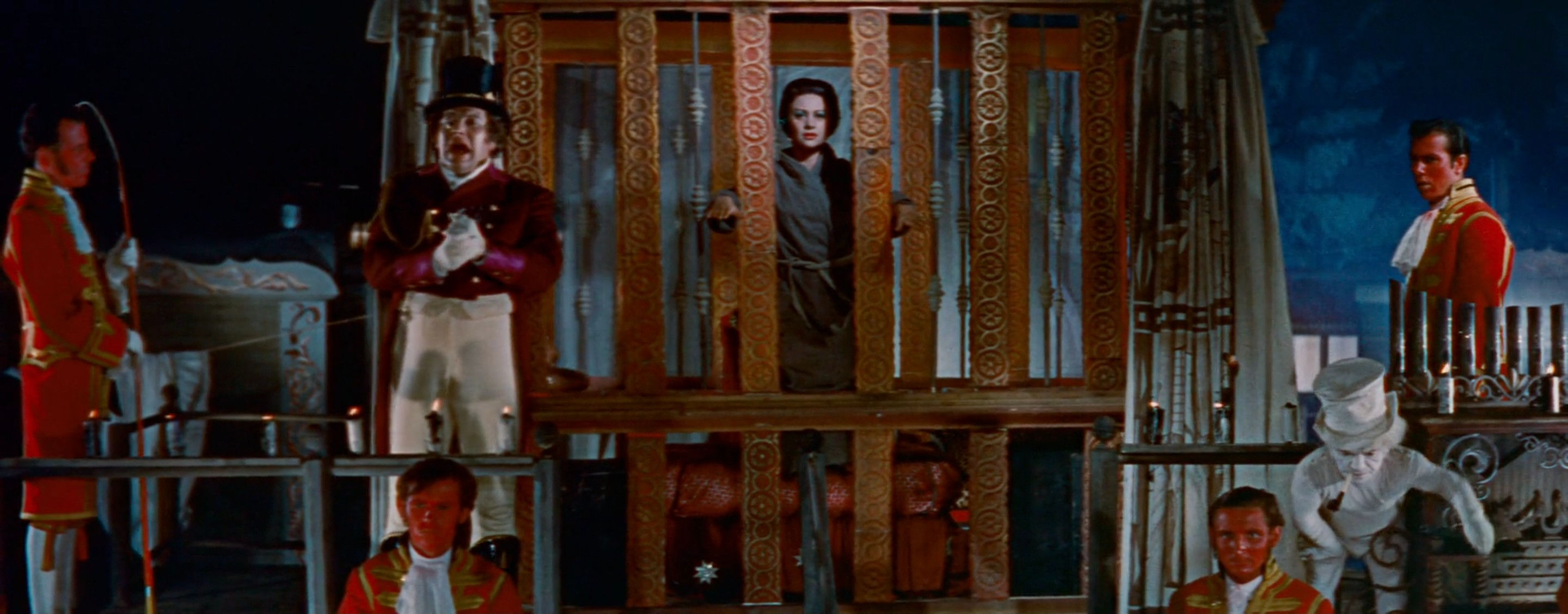

The metaphor is not easily lost on the ringmaster of the circus that has essentially turned Lola into a novelty attraction many years later. “Just as every single action in her life has been, every single movement of her act is fraught with danger. She risks her pretty neck!” he cries, narrating her ascension up a grand trapeze, and labelling each acrobat who catches her in their arms as a new lover.

“Paris! Destiny sends her from the famous journalist Dunarrier to the journalist Beauvallon whose newspaper had a larger circulation. The great and celebrated Richard Wagner. The even greater and very famous Frédéric Chopin falls on his knees for her. Higher, Lola, higher! With dance and music, Lola rises from the world of art to that of politics!”

At the summit of this towering web of ropes and ladders, King Ludwig I of Bavaria awaits, ready to commence what will be “the most fantastic episode of her story.” Still, there is more than a hint of phoniness in the ringmaster’s theatrical rendition. His claim that her marriage to one Lieutenant James was a happy one is immediately undercut by her recollection of his drunken, abusive behaviour, exposing the scam of this fanciful historicising. As Lola Montes progresses, this tension proves to be key to Max Ophüls’ elaborately symbolic framing device, glamourising her rise to fame while forcing her to relive decades of objectification in her neatly interwoven flashbacks.

Indeed, Lola’s eventual fate as a target of the male gaze is written into her destiny from the start, not just as a courtesan flitting between lovers, but simply as a woman born into a patriarchal culture with limited options. Whisked off to Paris at a young age to marry a banker, she quickly recognises the power of her charm and natural beauty to carve out a future of her own choosing. The attention that Lola receives wherever she goes cannot be avoided, and so the best she can do is use it to her advantage, embracing her feminine image whether she is posing for royal portraits or standing atop garish pedestals.

As Lola marches even deeper into the annals of history, the undercurrents of time and providence swirl around her, and Ophüls’ sentimental, untethered camera is there swaying with them. More than just linking one stunning composition to the next, it manifests an ethereal elegance as it cranes up and down through theatres in long takes, and tracks the movement of characters across ravishing sets. The effect is intoxicating, yet in the hands of cinematographer Christian Matras it is also totally controlled – not at all a surprise given the mark he left on the poetic realism of the 1930s, further solidifying the line of influence between Jean Renoir’s roving camerawork and Ophüls’ own distinctive visual style.

Tied up in the work of both these directors is a tension between freedom and fatalism, and it is largely through the careful navigation of the camera in Lola Montes that both are so gracefully connected. For a long time, Lola would like to think of herself as a woman with boundless autonomy, even ripping open her bodice in her first private meeting with Ludwig I just to prove a point. Nevertheless, she still recognises on some level that she is trapped within the gendered rules of high society, and Ophüls frames her as such in opulent displays of Technicolor decadence, making this both his first and last film shot in colour before his untimely death a mere two years later.

Whether actress Martine Carol is wandering through a rundown children’s dormitory of grey hammocks or draped in the finest royal garb, there is an air of delicate eminence to her, even as lush period décor and fluctuating aspect ratios press inwards like stage curtains. She is the luminous centre of each setting, asserting a screen presence that demonstrates why so many considered her France’s response to Marilyn Monroe, despite Lola’s dark wigs covering up Carol’s usual blonde hair. Cloaked in sparkling jewels and surrounded with extravagant historical décor, it isn’t hard either to see where the budget went for what was the most expensive European film of its time. Mirrors catch her reflection as she contemplates an uncertain future, transparent gauze drapes conceal her final goodbye to Ludwig, and the golden embellishments of Bavarian palaces frame her as another treasure added to the royal collection, lifting her to even greater heights as an inhuman object of imperial perfection.

The majesty of Ophüls’ production design does not cease when we cut back to the present-day circus scenes, but for as long as Lola stands onstage under the vibrant wash of red and blue lights, she is much more exposed than she ever has been before. She has certainly suffered in the public eye before, even becoming a widely hated Marie Antoinette-like figure spurned for her perceived “insult to dignity, morality, religion,” yet while courting Ludwig I she at least had the safety and privacy of the palace to protect her. As a carnival attraction, she is thoroughly humiliated, and her autonomy is destroyed. Everyone’s eyes are still on her, but there is nowhere to retreat in the middle of this stage.

After a lifetime of never finding the security she craved, this is the life she wearily resigns to. She is filled with miserable self-loathing as she escapes the March Revolution of 1848, rejecting a friend’s romantic proposition not because of his lowly status, but because she no longer believes she is worthy or capable of love.

“I’ve lived too much, had too many adventures. Bavaria was my last chance. My last hope of a haven. It’s all over… all over. You see, if this warmth you offer me, if this face which I find not too unpleasing leaves me without hope, then something is broken. Yes, it’s over.”

The Lola who is forced to recount her life through ostentatious circus acts bears a pale resemblance to the one who is said to have bathed nude in Turkey for the sultan and served champagne from her slipper. Backstage, we learn of her medical concerns that are carelessly brushed off by the ringmaster, maintaining that she performs her climactic acrobatic leap without a safety net. Just as she once lived at the top of European society with the King of Bavaria, so too does her fall risk destroying everything she once had, landing her in a menagerie of exotic beasts similarly trapped behind bars. The camera floats back over the heads of audiences lining up to stroke her hair or kiss her hand, revealing an enormous line that could singlehandedly keep this circus running for years, though it isn’t until a pair of clowns close the red curtains on us that Ophüls lands Lola Montes’ final, scathing critique. Everything from Lola’s childhood dreams to her multiple romantic affairs has been little more than a cheap show for this culture of perverse celebrity worship, seeking to degrade the lives of great women into objects of commodified, gaudy spectacle.

Lola Montes is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.

Pingback: The 100 Best Shot Films of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Cinematographers of All Time – Scene by Green