Paul Schrader | 2hr 1min

The debate over whether we might better understand an artist through their creations or their life is rendered meaningless in Paul Schrader’s exacting study of Yukio Mishima. With one prophetically mirroring the other, the two make up balanced parts of an equation, filling in the gaps that are left behind in the wake of the Japanese writer and soldier’s premature death. This perfect synthesis of mind and body is just as essential to Mishima’s ideological mission as it is to Schrader’s formal representation of him, with both pursuing a beauty that encompasses the equal need for words and action to create a spiritual wholeness.

“In my earliest years I realised life consisted of two contradictory elements. One was words, which could change the world. The other was the world itself which had nothing to do with words. For the average person, the body precedes language. In my case, words came first.”

As much a biopic as it is an adaptation of his writing, Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters splits itself into quarters, announcing the titles of each at the very start like a contents page – ‘Beauty’, ‘Art’, ‘Action’, and ‘Harmony of Pen and Sword’. Next to scenes of Mishima’s childhood, army training, and growing resentment towards the “big, soulless arsenal” that is modern Japan, the first three chapters also intercut his life with several adaptations of his novels too, titled The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, Kyoko’s House, and Runaway Horses.

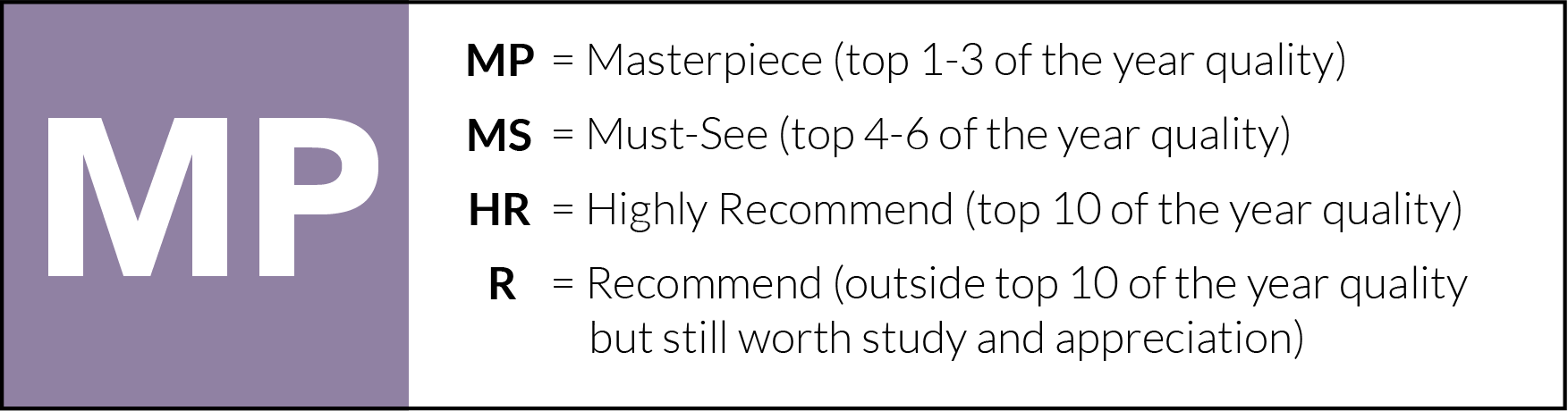

The difference between these worlds of reality and fiction is striking. There is an austere beauty to the black-and-white photography that captures Mishima’s life, eloquently teasing out his traditionalist philosophies like poetry right next to his pensive voiceovers. Long nights are spent refining the craft of his writing, considering ideals of beauty, masculinity, and death with reverence, and then boiling them down to artistic abstraction. Seeing the decay of the human body as a total loss of dignity, and regarding his own poor health with insecurity, he spends an equal amount of time honing his physique as well. “Creating a beautiful work of art and becoming beautiful oneself are identical,” he proclaims, thereby embodying a rigorous discipline rooted in the samurai code of honour. Practically, this also manifests as a nostalgia for Japan’s proud history that was ousted with the introduction of democracy, and which now motivates him to restore the emperor’s rightful political power.

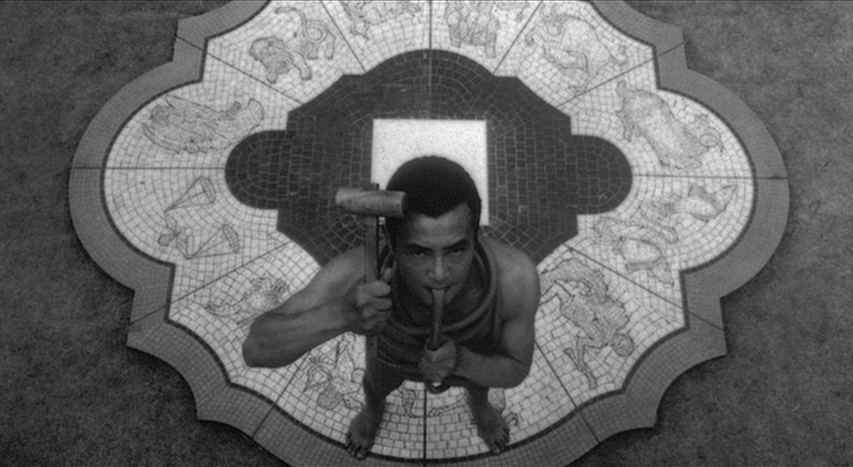

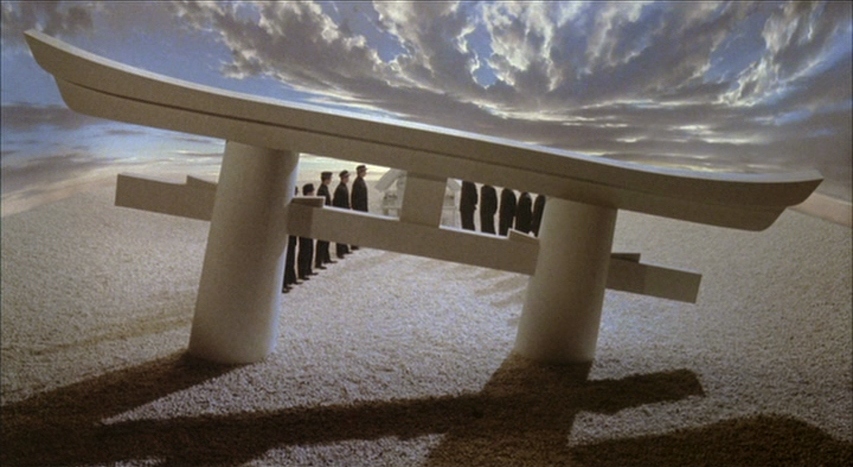

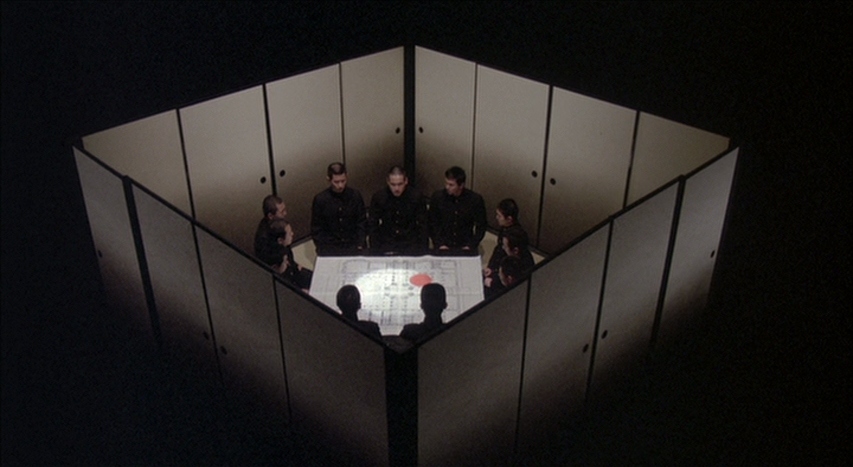

In contrast to the monochrome starkness of Mishima’s life, all three of his adapted stories explode with bright neon and pastel colours across rigorously curated sets, effectively becoming theatre stages bordered by darkness. Schrader does not shy away from the artifice here – every shot is imbued with the impressionistic imprint of Mishima’s artistic passion, separating these fictional tales into their own self-contained worlds. With red paper leaves fluttering around a golden temple, neon pink lights shining through Venetian blinds, and a white Shinto shrine standing askew and half-buried in a plain of white gravel, each tableaux represents a new, whimsical world that springs from Mishima’s dreams, carrying great symbolic weight.

Schrader curates his deeply sensual colour palettes in these segments with care, accomplishing a painterly aesthetic that speaks directly to each tale of beauty, art, and action. No doubt there is a part of himself that is present in his protagonists too. In The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, one man’s destruction of a Zen Buddhist temple asserts victory over the notion that beauty can be immortal, while Kyoko’s House follows an actor’s sadomasochistic relationship with an older woman that ends in murder-suicide, subscribing to the notion that life must end before one’s physical deterioration. Perhaps the most prescient of all though is Runaway Horses, which sees a right-wing radical attempt a coup on the Japanese government before committing suicide via seppuku.

Despite their incredible visual distinction, the parallel editing between reality and fiction is deftly executed throughout the film, elegantly fusing the two in graphic match cuts and through a pacing that hurtles forward with all the urgency of a man desperately chasing down his destiny. So too does Philip Glass’ avant-garde score match its propulsive energy with wildly fluctuating arpeggios and ever-shifting tone colours, using string quartets for Mishima’s life and a symphonic orchestra for his adapted novels. There are few composers more suited to the task of scoring a Schrader film than Glass, especially given their shared artistic obsessions with minimalism, form, and the repetition of phrases that build rhythms to scintillating climaxes.

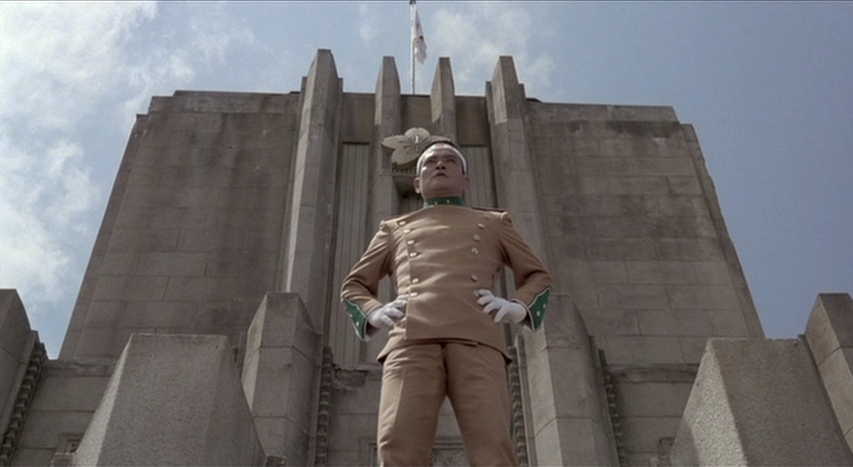

Absolutely crucial to these persistent patterns underlying Schrader’s narrative though is a third narrative thread, distinguished from both the black-and-white recounts of Mishima’s life and his vibrantly artificial stories. Its aesthetic finds a balance between both, being shot in colour yet very clearly existing in the real world. The glimpses it provides of Mishima’s last day punctuate the start of each chapter, seeing him dress in the uniform of his private militia and set out with four of his soldiers to make a final stand against the government of Japan. With military drums joining the mix of Glass’ score, there is a gravity to these careful proceedings, culminating in the final chapter of the film where it becomes the centrepiece of Schrader’s narrative. There is no fourth short story adaptation here, painted with bright pigments. Mishima’s martyrdom is the destiny he wrote for himself a long time ago, and which he now embraces with fury and passion.

For all his flaws, it is hard not to feel some level of pity for this right-wing radical as he shouts his message from the balcony of an army garrison, lamenting the loss of Japan’s spiritual foundations and demanding that his fellow soldiers join him in restoring the emperor to his throne. The low angle that centres him as a commanding figure backed up by the giant stone building behind him is almost immediately undercut by the jeers thrown from below. Refusing to let them drown him out, he continues his verbal crusade, long past the point that anyone else would have stepped down. Realising just how lonely he is in his noble convictions though, he pauses, and finally delivers a poignant admission of defeat.

“I have lost my dream for you.”

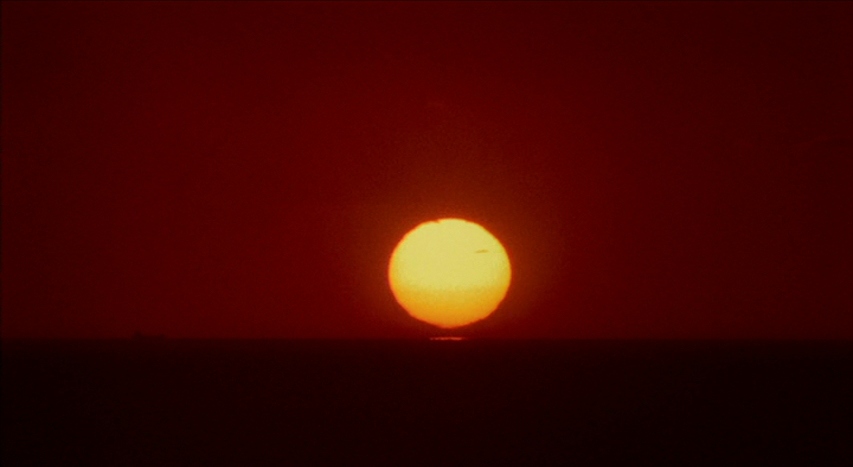

Retreating inside to where his loyal men wait for him, he draws his samurai sword to perform seppuku. At this moment, Schrader delivers a stroke of formal genius with the concluding shots of all three of Mishima’s stories, reconciling both art and action with a burst of vibrant images that were previously withheld. The temple burns in a symbol of fleeting beauty, the lovers lay dead, and much like Mishima himself, the radical nationalist of Runaway Horses plunges a sword into his belly, pursuing a greater moral idea to his own tragic detriment. Still, the voice of our protagonist remains, poetically situating himself at the forefront of his own narrative as he bears witness to his own blaze of glory.

“The instant the blade tore open his flesh, the bright disk of the sun soared up behind his eyelids and exploded, lighting up the sky for an instant.”

Mishima does not achieve the political victory he set out to accomplish, but as a man born out of time, that was never possible. Under Schrader’s steady hand, we instead bear witness to his spiritual enlightenment, as Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters unites those dispersed fragments of his art, philosophy, and being under the consolidating bond of death.

Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.

Pingback: The 100 Best Screenplays of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 50 Best Screenwriters of All Time – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 100 Best Film Scores of All Time – Scene by Green