Wes Anderson | 4 episodes (17min to 41 min)

Not even two months out from the release of Asteroid City, Wes Anderson has continued to break down that fourth wall between storytellers and audiences with his deadpan theatrics, though this time in the spirit of literary adaptation. Having previously translated Roald Dahl to screen in 2009’s Fantastic Mr. Fox, he is no stranger to the author’s modern fables of monsters and outcasts, both of which bear especially close connections to his own experiences living through wartime and post-war Britain in these four shorts. The brief, handwritten notes at the end of each instalment offer some context to their writing, whether inspired by the eccentric local townsfolk of Amersham where he penned The Rat Catcher, or a newspaper account of a real bullying incident that stayed with Dahl for thirty years before using it in The Swan. Even within the settings themselves, the relevance to his own military service is clear as well, with both Poison and The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar using Britain’s imperial rule of India as a backdrop to stories of greed and racial prejudice.

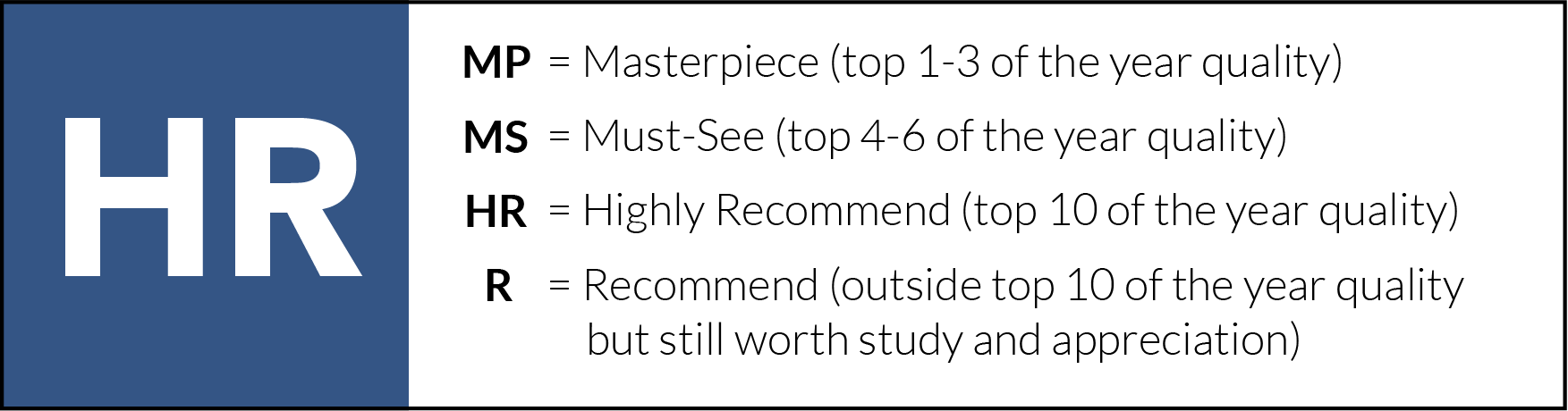

As far as familiarity goes in Dahl’s work, these tales are not quite as widely beloved as Charlie and the Chocolate Factory or The BFG, yet Anderson is purposeful in his curation, painting out a larger portrait of alienation across the entire collection. It is there in the rodentlike characterisation of the titular Rat Catcher who recoils from the disgust of others, Peter’s psychological and physical torment at the hands of two bullies in The Swan, and perhaps most cuttingly the vitriolic racial slurs spat at Dr Ganderbai that give a double meaning to the title Poison.

When it comes to The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar though, the longest of all these short films, Dahl and Anderson angle their story towards a hubristic self-isolation resulting from one wealthy bachelor’s obsessive pursuit of greatness. Having spent years as a recluse in his London apartment trying to learn the ancient Indian trick of seeing without one’s eyes, Henry finds himself totally unfulfilled by the fraudulent success it grants him in casinos. His loneliness is entirely of his own making, emerging from an arrogance that is ultimately washed away by the ancient form of spiritual meditation he has been practicing, and guides him towards a lifetime of redemption.

Of the four shorts, The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar is the only one that ends on such an optimistic note, while Anderson takes some liberties to end each of the others with unresolved bitterness. After Dr. Ganderbai exposes the snake apparently lying on one terrified man’s chest in Poison to be in his head, he does not brush off his humiliated patient’s racism with the happy-go-lucky attitude of his literary counterpart, but rather leaves him with nothing but cold silence. Similarly, Peter’s fate after being forced to jump from a tree in The Swan is a touch melancholier here than in Dahl’s version, with Anderson choosing to close on the poetic image of Peter’s adult self crumpled on the ground, unrecovered from his childhood trauma. To Anderson, worldly evils such as those suffered by our protagonists cannot simply be healed over with a cheerful shrug or a band aid. They persist in the memories of their wounded victims, and are imparted to the world through the eloquent expressions of great artists.

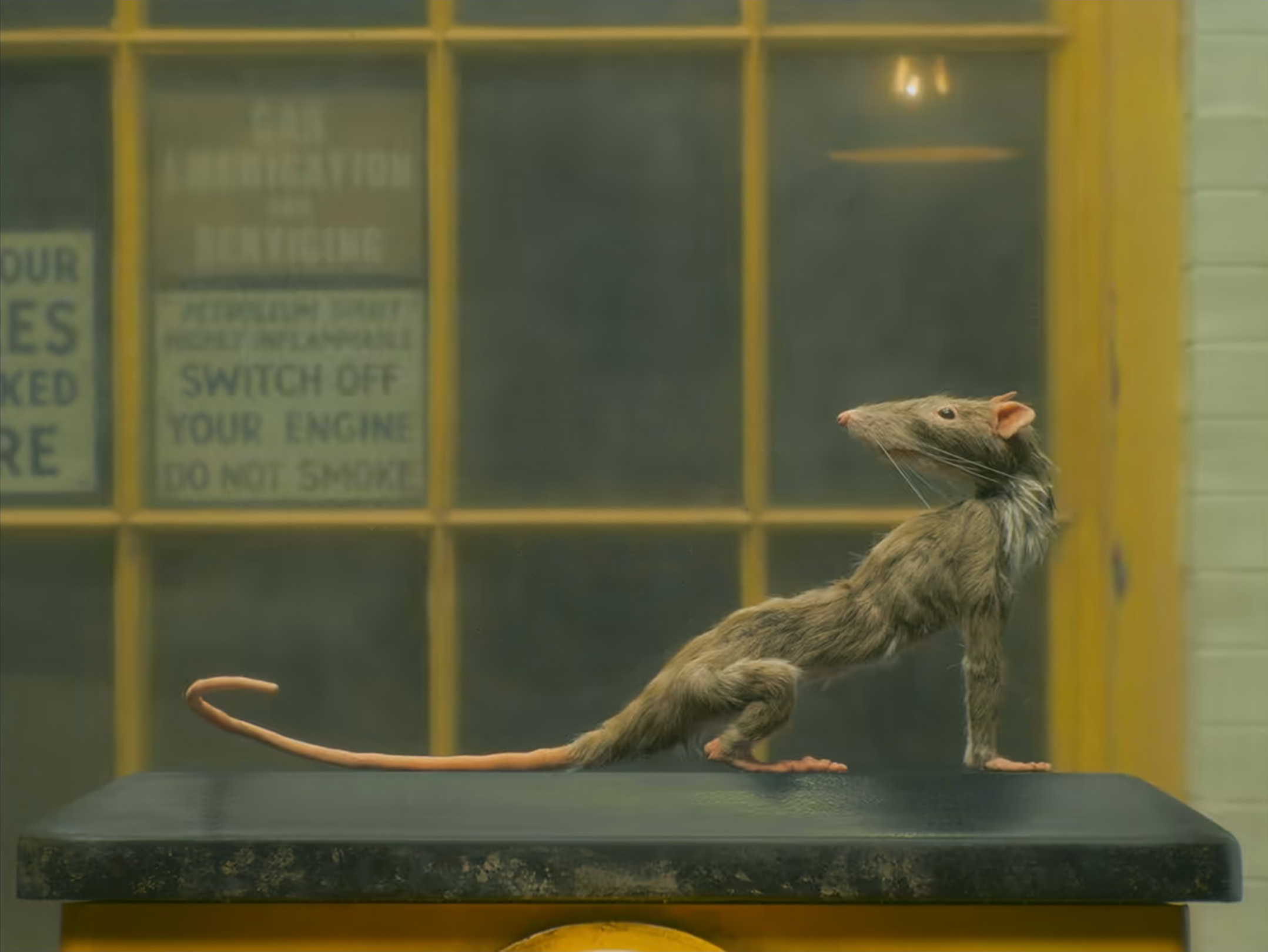

It makes sense then why Anderson chooses to use a physical representation of Dahl as a narrator in each of these stories. More than any of his fictional characters, Anderson sees pieces of himself in the writer, both being storytellers who offer a veneer of whimsical innocence that may entice children, only to reveal quiet tragedies beneath the colourful surface. Anderson’s screenplay is dense with narration lifted mostly verbatim from the source material, passing from Dahl sitting comfortably in his home on the outermost layer to those characters within the stories themselves. From there, actors effortlessly switch between direct addresses to the camera and in-scene dialogue with barely a pause, moving narratives along at an extraordinarily propulsive pace that may be unforgiving to those viewers who let their attention wander for more than a few seconds.

For many directors, this endlessly babbling stream of descriptive soliloquys would be a hindrance to the visual medium of cinema, and though Anderson is slightly more limited here in his staging than usual, his craftsman hands deftly mould Dahl’s words into the equivalent of a pop-up storybook unfolding on giant stages. Specific props and characters are occasionally absent, encouraging a childlike imagination as actors mime and interact with empty space, while other illusions such as Henry Sugar’s levitation is achieved with little more than a camouflaged box. With his rear projection, pastel dioramas, stop-motion animation, and mobile sets visibly moved by backstage crew, Anderson lays the artifice on even thicker than usual, arranging every shot to a level of symmetrical perfection that keeps us at a Brechtian distance from any impression of reality.

Anderson’s aesthetic trademarks are distinctly recognisable from film to film, yet the theatrical designs and formal elements of these shorts bind them even closer as a single cinematic work, rarely even straying outside its single troupe of actors who rotate between roles. Ralph Fiennes, Benedict Cumberbatch, Rupert Friend, Ben Kingsley, Dev Patel, and Richard Ayoade each play an assortment of outlandish characters, while among them Fiennes is the only one to appear in all four instalments, taking on the additional role of Roald Dahl himself. His gentle demeanour there is hilariously offset in The Rat Catcher when he comes to solve a small village’s infestation with claw-like nails, beady eyes, and a pair of long front teeth, suggesting his ethos to ‘think like a rat’ has spread to his grisly appearance and behaviour, and thereby showing off Fiennes’ impressive acting range. Perhaps just as impressive though is Friend’s solo command of The Swan, adopting the nasally voices of other characters in an enrapturing monologue like a parent might while reading to their child at bedtime, and Cumberbatch’s turn as Henry Sugar himself, easily the most fully developed character of the lot.

In an era of streaming that has seen directors like Barry Jenkins and Nicolas Winding Refn dip into auteur television, Anderson’s own fascinating formal experiment pushes the medium beyond the usual episodic series, while delivering a natural extension of his filmography up to now. Fictional magazines, plays, novels, and memoirs have inspired his inventive structures before, and now his adaptation of Roald Dahl’s short stories into a loosely connected anthology continues that trend of exploring more traditional media through versatile cinematic forms. If there is any hindrance to his talent here, then it is the sheer difficulty of developing any character or story within the limited scope of 17 minutes, and yet at the same time there is far more excitement in any one of these isolated shorts than most films being made. The spirit of Dahl’s literature is alive, taking creative form in Anderson’s poignantly whimsical fables of scheming psychics, merciless bullies, zealous exterminators, and petrified patients.

Wes Anderson’s collection of Roald Dahl shorts is currently streaming on Netflix.

Pingback: The 25 Best Male Actors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 10 Best Screenwriters of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The 25 Best Directors of the Last Decade – Scene by Green

Pingback: The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar and Three More (2024) Review: Brilliant, Unforgettable Wes Anderson Anthology - Movie Block